As a director, Christopher Nolan uses secrecy as a driving force behind the writing and marketing of his films. His films invite the discussion of spoilers, thriving on their ability to conceal some sort of mechanism toward which the film builds. Often, the result is spectacular: the organic and dynamic release of action and information demands that viewers re-contextualize their understanding of all preceding events. These are the sorts of moments that legitimize Nolan’s attention to the primacy of narrative, that excuse his reliance on opposition, and that celebrate his occasionally haphazard sprinklings of philosophy.

Nolan’s films are Trojan horses, masking their old-school sentimentality and human concern with the cerebral register of storytelling that has become the director’s hallmark. This is not a criticism: Nolan’s best work is a result of this inversion of priorities. “The Prestige” purports to be an exploration of illusion while covertly crafting a portrait of friendship and obsession. “Inception” outwardly examines dreams and their intersection with reality while quietly devoting the heart of its story to questions of loss and mourning. In his new film, “Interstellar,” Nolan explores the nature of spacetime and the fate of humanity while organizing the picture’s most powerful moments around a discussion of family and the tensions between the desires to explore the unknown and to cultivate intimacy.

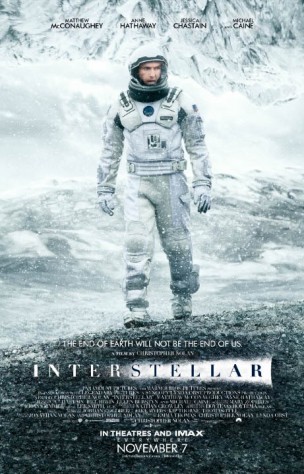

“Interstellar” is a blindingly ambitious film: gorgeously shot, wonderfully acted, and, finally, horribly organized. It has the ability to awe, inspire, frustrate, disappoint, and provoke. It depends on—and fails as a result of—a love for and a devotion to mystery. It is also immensely difficult to discuss, both because of its reliance on the cards it has stashed and because it manages to be Nolan’s weakest, most infuriating, and most promising production to date.

The basics of the plot are simple enough: Earth is dying, slowly and indelicately. Due to massive dust storms and inhospitable weather, humanity’s food supply has been dwindling for years, along with the human population. With each passing year, and with each new wave of extinction, the future looks more and more grim. Humanity must find a new home.

Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) is an ex-NASA test pilot, who, like most of the world, now tills the earth. He lives with his two children—his daughter Murphy and son Tom—and father-in-law, but dreams of the life he once had. One evening, Cooper and Murphy stumble upon a secret underground NASA bunker. There, he meets an old colleague, who convinces him to take part in a galaxy-spanning mission to find humanity a new place to live. The drawback: he may not be home for years, if at all.

The film can be divided into roughly five sections, and it’s hard to say which of them, if any, is the most successful. At 169 minutes, the picture drags, and its episodic reliance on the exploration of different worlds becomes frustrating almost immediately. Nolan does a remarkable job of visualizing these alien landscapes, painting them in simple, spare, mono-elemental tones that prove both digestible and memorable, even as they fail to cohere. Yet try as he might, the director finds little meaning or life in these locales, which ultimately feel like pit stops along the way to the film’s conclusion.

This is all the more troubling when held against the film’s work in setting its scene on Earth, where Cooper’s children languish in a state of despair, rage, denial, and determination for the majority of the movie. Leading up to Cooper’s departure (which occurs roughly at the 30 minute mark), “Interstellar” dawdles, mixing moments of poignancy with others that suggest some sort of world-building that the picture never really expands upon. Certainly, the circumstances of Cooper’s departure are heart-rending, and McConaughey plays them with fearless, sentimental commitment. In what may be the best scene of the film’s numerous trailers, Cooper drives off in tears, checking under a pile of blankets in the passenger seat of his pickup, hoping that his daughter has decided to stowaway there as she has before. It’s a sharp and un-showy moment that remains far more powerful than the film’s many stunning depictions of space.

This is not to say that “Interstellar” skimps on spectacle. The film takes pleasure in attempting to depict that which cannot be depicted in our universe and most often succeeds. Certainly, it’s strange to think that some of the great mysteries of our heavens might look like an iTunes visualizer, but, all the same, the film’s scope allows it to indulge a sense of immensity that cannot be understated. For “Interstellar,” space is not the great merciless void of Alfonso Cuarón’s “Gravity.” Rather, it is a jungle of the metaphysical, in which silence is compensated for with extravagant color and form.

As with many of Nolan’s films, “Interstellar” is an exposition machine, with various players spouting off rapid-fire explanations of our universe’s most complicated anomalies. At times, this can be fascinating: it’s exciting to have a science fiction film that seems so thoroughly in love with the science at its core. At the same time, however, Nolan often seems unsure of his own commitment to this very science. Though character decisions are often backed by extensive discussions of theory, the film also has the tendency to veer into the patently unscientific. In most cases, this would not be a problem. Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” gained much of its own impact from its strange, poetic, and psychedelic handling of science, and at points Nolan’s picture seems to compare itself explicitly to Kubrick’s; yet in Nolan’s case, it just seems half-hearted.

By the time the film reaches its climax, it has drained itself of everything but the narrative shadow of Kubrick’s work. At times, Nolan strives for the sort of recursive weirdness that Kubrick himself used in “The Shining.” In “Interstellar,” that interest seems like a put-on. Where Kubrick’s interest in recursion hinged on his picture’s eerie mood and boldly flew in the face of logical convention, Nolan’s attempt at the same trips over itself trying to find narrative structure that will somehow make the illogical sensible. The result is strange and frustrating, a seeming take-back of the hours the director spent asking his viewers to study the science of his premise.

This is only exacerbated by Nolan’s handling of metaphor, which consists of the selection of four or five motifs or images, and the subsequent repetition of those images ad nauseam. Minor context changes do little to showcase the director’s adaptability as a writer and frequently threaten to undermine the film’s use of symbols. Dylan Thomas’ “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” is recited by nearly every character in the film, to the point where one wonders whether Nolan knows that other poems have been written. Though at first the opening words become a battle cry of resilience, adaptability, and survival, they end the film as the exact opposite: a grumbling acknowledgment of a lack of thematic versatility. If that one poem were Earth, surely Christopher Nolan’s vision of humanity would dig in their heels and die there.

None of this is to say that “Interstellar” is a strictly bad film. It’s visually splendid and, at times, unmistakably moving. Yet it is a deeply confused film, repeatedly unsure of how it wants to approach its genre, mechanics, characters, and themes. It indulges both a Spielbergian devotion to wonder and a documentary diffusion of its own mystery. It can be maddeningly recursive at times, drawn out and full of itself, while still eliciting vivid responses from the audience. It would be too easy to call “Interstellar” a flawed masterpiece, nor would it be fair to call the film a wonderful failure. In a sense, it resides in a category all its own, tugging at its director’s standard technique while forcing him far beyond his comfort zone. The result is baffling. It’s also necessary viewing.

Leave a Reply