Many of us have more pressing concerns than what happens after death. After all, midterms are upon us, so now is simply not the moment for an existential crisis.

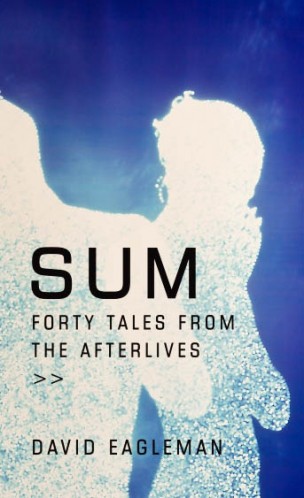

Nevertheless, David Eagleman’s humorous, intelligent, and sometimes alarming look at the possibilities of the afterlife in his 2009 book “Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlives” is a more-than-worthwhile read. Possessing an unusual double identity as both neuroscientist and author, Eagleman has written several books on subjects from synesthesia to the importance of the Internet.

“Sum” is composed of 40 possibilities for the human experience after death. The possibilities are each presented in two to three pages and take the form of vignettes rather than short stories; it may be surprising to readers that a book devoid of developed plot could be quite so captivating. The unusual adoption of the second-person voice draws the reader in and forces self-reflection. Each tale resonates with the imagination and easily could be the inspiration for a narrative, but that might be pointless; Eagleman has distilled the most thought-provoking parts of each world and presented them without commentary or superfluous information.

This book may be of particular interest to those who have read and enjoyed the “His Dark Materials” trilogy by Whitbread Book of the Year Award recipient Philip Pullman. Eagleman adopts a similarly whimsical-yet-deep perspective on the afterlife, and Pullman gave “Sum” a positive review. The two authors collaborated on reading of their work in England several years ago, with Eagleman reading “Sum” and Pullman reading his most recent book, “The Goodman Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ.”

Eagleman describes himself as neither an atheist nor an agnostic, but rather as a “Possibilian.” Applying his scientific mindset to the concept of religion, Eagleman coined the term to imply that while we know too much to believe in some things, we know too little to rule out all alternatives.

Several of Eagleman’s stories do seem to make pointed commentary about religion as it exists today. One story concludes, “It is not the brave who can handle the big face [the creator of the Universe], it is the brave who can handle its absence.” Another satirizes wars between religious groups. Most stories fly in the face of most classic conceptions of “greater beings.”

“Sum” opens with the hypothesis that after death, you relive your life’s events grouped together by activity. This includes the good (“seven months having sex”) and the bad (“seven hours of vomiting”), removing any notion that there is a heaven and a hell—everyone experiences the same fate. (The “eighteen days staring into the refrigerator” resonated particularly strongly with me.)

Some stories are haunting. One vignette says that when you die, your life continues as normal, except that the only people in the world are the ones you have known. Though you will get to spend time with those you have loved, there will be no strangers and no industry. If you feel unsatisfied with your relationships or your body of knowledge, Eagleman says, no one will sympathize: this is the life you have chosen for yourself.

Other stories are less about self-reflection and more about our conceptions of the universe. Though these were the only ones that occasionally seemed repetitive, they still presented interesting scenarios. In one, we are tiny parts of a giant living person, unable to meaningfully communicate with her. Another tells us that after death, we are kept around to be actors in the lives of living humans.

Though many scenarios are godless, Eagleman’s worlds are populated with all kinds of deities. There are clever ones, bored ones, stupid ones, and kind-but-misguided ones. The one thing they all have in common is that they all have human characteristics, perhaps a nod to the fact that these stories are coming from a human brain, but more meaningfully perhaps an acknowledgment that some traits are universal, no matter your size or importance.

Most stories end with a punch in the gut, an interpretation of or conclusion to the given scenario that reminds readers of their own humanity. Depiction of human life on Earth through the eyes of one with knowledge of our lives and afterlives is humbling. Though Eagleman recognizes the good in people, he does not gloss over the selfishness, cruelty, and ignorance.

Eagleman has a way of putting into sound bites the conclusions of philosophical discussions that would normally take hours.

“Everything that creates itself upon the backs of smaller scales will by those same scales be consumed,” he concludes in one tale. However, most of his conclusions are more subtle and live in the world of the story, opening doors of musing within the “you”s that he addresses.

All 40 vignettes embrace the notion of Possibilianism. Throwing away known rules of time and space, Eagleman turns the impossible into the oddly rational.

Leave a Reply