With the premiere of the first episode of the fourth (and final) season of “The Legend of Korra,” we have a lot of rebuilding to do: a government or two trying to repair themselves, a nomadic people working to bring themselves back from the brink, and the world’s supposed protector fighting to become whole again. Let’s just say that over the previous season of “Korra,” the franchise’s darkest, bloodiest, and best season so far, a great many things were blown up.

“The Legend of Korra” was originally conceived as a miniseries, set two generations after the end of “Avatar: The Last Airbender.” It is at once a tribute to, a continuation of, and an improvement on the beautifully fleshed-out world, intricate geopolitics, and deep mythology of the original series. “Korra,” which began in 2012, maintains many connections to the original, which ended its run in 2008: The descendants of the original Avatar gang (Aang, Katara, Sokka, and Toph) now live in the new world established by Avatar Aang after the defeat of the imperialistic fire nation. Aang established the United Republic of Nations, with Republic City as its capitol, as a place where benders from all four former nations (as well as non-benders) could live in harmony. After his death, a new avatar was born: the titular Korra, of the water tribe.

Along with the usual four elements, metal bending (which Toph invented back in the original series) and lightning bending (seen originally as evil) are now commonplace and have been used to herald this world into an industrial revolution of sorts. I had a friend who quit watching early on in “Korra” because she couldn’t stand the fact that there were cars around. For me, the not-quite-steampunk world is even more exciting than the original because it feels more real and less forcibly connected to a magical, pastoral past. (Also, giant robots are cool.) Rather than traversing the lands as in Aang’s classic Hero’s Journey, “Korra” stays tied, more or less, to the industrialized metropolis, along with all the possibilities and problems that an urban setting holds.

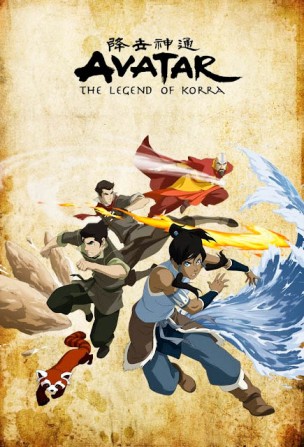

In its three seasons so far, “Korra” established itself as a darker, more politically tinged show than a children’s cartoon on Nickelodeon has any right to be. In fact, midway through season three, the network pulled it from the air, premiering the rest of the season’s episodes online only, where it currently resides at the beginning of season four. Book One (Air) places Korra and her newfound Team Avatar—fire bender Mako, his earth bender brother Bolin, and tech-savvy but non-bending Asami—against a populist uprising: the Equalists, who seek to even the playing field for ordinary citizens by removing all bending from the world. For a show based around the idea that a kid who can master all forms of magic should make decisions about the fate of the world, even giving a voice—let alone a persuasive one—to an opposition movement, turns this show into one quite comfortable dancing around the gray areas of morality and power.

For those who don’t remember, the ultimate moral conflict driving “Avatar: The Last Airbender” to its conclusion was one of life, death, and utilitarianism: Is Aang just in killing a terrible ruler if that death would save the world? Does the Avatar even have that authority, and how would that change him as a person? While “Avatar” strikes a serious blow in favor of saving life, “Korra” doesn’t avoid bloodshed so readily. Season one concludes with the murder-suicide of a corrupted government official and his brother, the leader of the Equalist rebellion, and somehow, it feels like the right thing to happen. Season three most likely was pulled from the air because of the graphic, on-screen suffocation death of a dictator: a member of an anarchist group literally sucked the air from her lungs. Later on, a member of that same group ended up blowing up her own head after it was encased in metal.

And yet, this series continues the matchless characterization work of its predecessor by humanizing even the enemy. I find myself questioning the unspoken dominance of benders over non-benders in society and governments, an issue that is never truly resolved and still sometimes pops up in the subtext here and there. Even the Big Bads have lives and personalities; just as Prince Zuko’s backstory turns him into the breakout character of “Avatar,” the interpersonal relationships of the Red Lotus anarchists turn them into something more significant than set-’em-up-to-knock-’em-down obstacles.

Not that “Korra” doesn’t have its issues. In the first season, a love square of sorts heralds all sorts of unwanted teen angst and overstays its welcome, while some characters, mostly on the side of good, do take a while to become fully fleshed out. The second season as a whole is a weak spot; its plot arc of bridging the real and spiritual worlds was never intended to exist when the miniseries was planned, and thus feels disconnected from the outstanding first season. Those holes, however, were mostly patched: the friendship dynamics and reconfigured world that were solidified in the third season will help start off the fourth season on more than solid ground.

So where exactly do we begin with “After All These Years,” last Friday’s season premiere? Set three years after the season three finale, it’s haunted by that episode’s ending image: Avatar Korra, confined to a wheelchair, shedding a tear. She was beaten down, kidnapped, and just about killed, almost the ultimate victim of that anarchy group that already brought down one government and was ready to send the rest of the world into chaos. Maybe Korra succeeded in defeating the enemy, but she left with more than a few scars of her own, and not just physical ones. Someone asks her in the season premiere, not recognizing who she is, what ever happened to the Avatar. She doesn’t know, she says. If “The Legend of Korra” was at any point conceived to be a children’s show, it is not one anymore.

Leave a Reply