Among the series that premiered in 2014, there was no show as promising, brilliant, and flawed as HBO’s new dramedy, “Looking.” Heralded by an almost comically wrongheaded and offensive review in Esquire in which a writer attacked the show for being boring and requested more of the fanfare he and his friends expect from the fictional gay community, the program seemed positioned as a daring new chapter in the mainstream portrayal of the gay community, treating its characters as, gasp, people. Esquire’s cheekily bromophobic takedown of the first few episodes seemed to only confirm this: “Looking” was a show that defied the expectations set by forerunners such as “Glee” and “Queer as Folk,” and that it offered a vision of gay life that would rattle those who were comfortable with the gay community as an entertainment quotient and no more.

In a whole host of ways, it has proven to be a more honest look at the nuances of gay culture. At its best, “Looking” is daringly and unpretentiously human, conscious of its context without asserting it as an object lesson. In many other ways, it falls flat. But, to its credit, it is a show that falls flat in far more daring ways than any of its predecessors, and often does so only because of the immensely high bar that the writing sets when the show is at its peak.

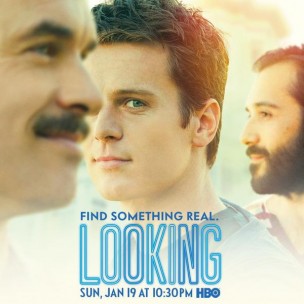

“Looking” is set in San Francisco and follows the lives of three gay men, played by Jonathan Groff, Murray Bartlett, and Frankie J. Alvarez. Each character is a sharp subversion of stereotypes, possessing qualities that seem generic or reductive on the surface but are bent and angled in unique and textured ways. The result is that each character feels wonderfully, frustratingly alive. At times, they are dumb, selfish, arrogant, and shallow. At other times, they are compassionate, witty, humble, and generous. They sit within a cultural context that, by virtue of its potential for support and camaraderie, often shapes the way in which they view their social roles, but that never defines them or overtly directs their choices. These are dynamically and daringly self-aware characters who are acquainted with the way they may be seen by others, both within and without. They act with nuance and passion, and often defiance, of both people and structures. They are intelligent and funny, but never at the expense of realism. They are not beholden to the stereotypes that haunt past fictionalized portrayals of gay men, auras that sought to both aggrandize and debase characters in order to remove them, at all costs, from the balance that would make them human.

“Looking” is also a show that demands intense scrutiny. As a program, it proves, along with the Glees and the Modern Families of the world, that heteronormativity is in no way based on heterosexuality. Even as it proves keenly observed and deeply felt, “Looking” only rarely directs its blistering and empathetic gaze anywhere but at the white gay man, who remains one of the few occupants of the many queer communities with whom so-called mainstream culture is comfortable engaging. Upon its arrival and throughout its run, “Looking” was praised for including multiple Latino characters, and there are moments during its first season where it brilliantly diagrams and discusses what those characters have to contend within a marginalized sphere that, itself, is more than happy marginalizing.

Too often, however, the experience of these characters becomes a conjugate of the experiences of the male-dominated ensemble. For instance, midway through the season, Groff’s character is accused by a friend of slumming because he has chosen to date a Chicano barber named Richie (portrayed magnificently by Raul Castillo). When the issue is brought up again, however, it has become an issue of whether Groff is ashamed of Richie, seen from Groff’s point of view and supplemented by a few quick shots of his partner looking anxious. It goes without saying that this is the less interesting and less honest route to take, but ultimately, “Looking” is full of missed opportunities such as this one.

On other fronts, the show struggles with the way in which it treats its female characters (an issue discussed in a nonfictional context by Jezebel earlier this year), but possesses slightly more self-awareness about this issue than other shows about the gay community. Many are all too comfortable deploying the offensive “fag-hag” trope in ways that benefit absolutely no one.

All that said, “Looking” is a show worthy of attention. Even as it struggles with the same questions of representation and inclusion that plague past shows of its type, it manages to at least engage with them beyond the point that viewers might have come to expect. It’s far from perfect, but vibrates with acumen and potential, seeming to promise a step forward in depictions of queer communities. “Looking” is consistently well-written and acted, with characters whose flaws are cogent markers of their humanity, as well as the evolution of their perceptions of their loved ones, their communities, and their responsibilities. Upon close examination, “Looking” and its characters seem to be working through many of the same issues. They both gesture toward notions of acceptance of self and community in ways that seem strikingly immediate and unique, while also universalized and transcended.

“Looking” is not perfect. It is far from perfect. It is unmistakably brilliant yet unquestionably problematic. However, it’s also one of the few shows that seems to care about where on that question it stands. “Looking” is a program that seems dedicated to growth, and it seems to be on track for a marvelous evolution.

Comments are closed