In the wake of “True Detective,” it’s far too easy to be reminded of the state of the crime drama on television, especially that niche of the genre dedicated to the almost fetishistic obsession with serial killers that Nic Pizzolatto’s show so artfully transcended. Truly, much of the praise for “True Detective,” especially during the beginning of its run, was directed at the program’s ability to move freely and intelligently within a space defined by stasis, clumsiness, and fundamental simplicity. HBO’s newest critical darling is proof that those tendencies that so hinder shows like “The Following” are not elemental to the genre, or the medium. They are combatable, transmutable, escapable. And, luckily for those who see the wait for Pizzolatto’s next installment as some sort of empty landscape, there is another show that consistently and wonderfully stands in opposition to its fellows. You’re just going to need a strong stomach.

NBC’s “Hannibal,” which is currently in the middle of its second season, seemed destined for failure from its conception. The title character had been canonized as a caricature of refined psychopathy in his latest cinematic appearances, almost entirely divorced from the refined, but still razored, brutality of “The Silence of the Lambs.” It seemed as though any reintroduction of the character would only continue along this path, turning him into one more flavorless television reaper, full of malice and culture orbiting around a self-consciously artificial core. At least, this is what I anticipated as I begrudgingly agreed to watch the pilot with my family. I’m happy to say that I was incorrect.

The show that has evolved over the past 19 episodes is a thing of grim beauty and scorching nihilistic intellect. It’s also one of the few pieces of mass media that is able to engage its gruesome fascinations while also locating an emotional core in their repercussions: a sense of loss, horror, and confusion. Developed by Bryan Fuller (of “Dead Like Me” and “Pushing Daisies” fame), “Hannibal” focuses on the character of Will Graham, a criminal profiler working with the FBI’s Behavioral Science team. Graham first appeared in “Red Dragon,” the first of Thomas Harris’ novels about Dr. Hannibal Lecter, the cannibal psychiatrist. Recruited by the FBI for his outstanding, and possibly dangerous, empathy, Will (played by a wonderfully understated Hugh Dancy) is able to almost literally walk in the shoes of the killers whom he is profiling. Working alongside Dr. Lecter, whom the FBI also brings on as a consultant, Graham finds himself caught up in an ever-expanding labyrinth of violence and manipulation, at the center of which he believes to be the charming but malicious doctor.

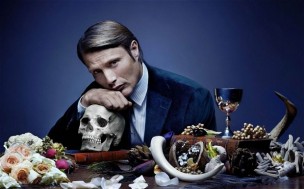

As portrayed on the show, Hannibal is a creature far different than any previous interpretation. Played by the wonderful Mads Mikkelsen, Lecter retains his trademark style and grace, but is stripped of the flamboyance that, in later films, robbed him of any real menace. Mikkelsen’s Lecter is an observer, a connoisseur of human emotion with no real attachment to any sense of compassion or decency. He is brilliant, and charismatic, but ultimately hollow and feral: an animal of perpetual morbid hunger and tailored wrath. In many ways, he is both a distillation of the psychopath of most modern culture— single-minded, unflinching, inhuman in a spectacularly sadistic way—and a commentary on that very archetype. Even as the viewers are aware of Lecter’s ultimate character (both through the show’s writing and the process of cultural absorption), they are treated to the urbane and intricate facade that Lecter uses to disguise his psychopathy to those around him. It is a testament to the program’s writing that, even as we know the truth about Lecter, the character seems alive enough to, if not fool us, charm us into turning the other cheek.

That is not to say that “Hannibal” reduces its antagonist to a tool for fulfillment of the show’s gore quota. Ultimately, Graham is the protagonist, and as Lecter tortures him, the show makes no excuses for the brutality of its eponymous evil. Fundamentally, the consequences of that evil are built into the tone of the show and the gloomy, ethereal, and baroque dream-state of Graham’s descent into something that may or may not be madness. With each killing that requires investigation, the over-the-top nature of the violence becomes a totem both of the wickedly surreal nature of the world in which this show takes place, but also of the way in which we have come to see these sorts of crimes: heinous, but titillating. This violence makes no attempt to convince you of its realism (such a battle would be unwinnable), but, rather, argues for the realism of the simple fact of the loss these elaborate crime scenes represent.

All of this really boils down to the show’s mastery of tone, which rivals, if not exceeds, “True Detective.” The world of “Hannibal” is one of constant tenebrism: shadow upon shadow writhing in a libidinous, decadent, and merciless continuum ripped straight from an El Greco, or Goya painting. The soundtrack consists mainly of dark classical pieces, operatic and as sumptuous as the dishes Hannibal prepares for his unsuspecting guests. It’s not that Fuller’s work attempts to find beauty in the inarguably hideous, but, rather, it drives at a sense of violence and madness as art. And, as opposed to creating a darkness and then abandoning it for the thrill of cheap pulp, “Hannibal” sticks to its guns. The show earns its oppressive unease with a dedication to depicting the toll that unease slowly and surely takes on its witnesses and its world, which proves to be one of immense emotional and relational complexity as portrayed by a brilliant cast.

It’s all too easy to dismiss a show like “Hannibal” on the grounds of its violence, which those who leave the show early on, or who simply refuse to explore its skeleton, might see as exploitative or shallow. This would be a mistake. “Hannibal” is a show of great intention and intelligence, and a show oriented towards a sort of visceral majesty whose gut punches are not merely there to turn the stomach. It’s also a draining program, harnessing the immense empathy and observance of its protagonist to deliver to the audience the sort of madness in which Graham finds himself embroiled. It’s one of the few serial-killer dramas that not only suggests a price beyond body count, but also consistently reinforces this theme, rather than abandoning it to get back to the rush of the slaughter. “Hannibal” revels in and unearths an elemental sadness in its genre that is far too often dormant on television, sharpening and deepening it with each case, each plot twist, each turn of the screw. It’s ultimately a very different show than “True Detective,” and in many ways, maybe even a better one. One thing’s for sure, though. No matter what Rust Cohle says, in Fuller’s little universe, the light barely stands a chance.

2 Comments

Anonymous

This is a great review, it pretty much sums up what I’ve been saying all along. So in all honesty, without the elaborate but striking wordplay, Hannibal is a great show, give it a try.

Bhammer100

People really need to start watching this. One of the best shows on TV. The praise is justified.