Earlier this semester, The Argus visited the Davison Rare Book Room, housed in Olin Library, to speak with University Archivist at the Special Collections & Archives (SCA) Amanda Nelson, who kindly showed us around the SCA’s extensive holdings. With over 10,000 feet of archival material and 45,000 rare books, the SCA represents a living, evolving record of student life, institutional change, and the University’s deep entanglement with global history and public memory.

The Argus: What exactly is Special Collections & Archives?

Amanda Nelson: We have just over 10,000 linear feet of material related to the history of the University. We have materials that date all the way back to 1831 and actually before that, with the founding of the University, and we continue to collect things now. My goal is always to create a snapshot of campus. It’s not just collecting the administrative point of view, but also faculty, staff, students, alumni, and all kinds of fun things. It’s a lot of working with groups and donors, and possible donors to see what they have that they are willing to donate, and how it can help us document and tell the story of Wesleyan. It comes in a variety of shapes and kinds.

We don’t have many objects, but we do have an early basketball. It’s what they called a season basketball, from 1909–1910. You can see it shows who they played and scores, and then I think it’s who got the game ball. It has different dates or different people’s names. We have some trophies. We have Wesleyan spoons and cups, and dinnerware. We also have t-shirts and hats that were worn by the football team back at the turn of the century or the late 19th century. We have letterman jackets. We have things from fraternities that existed here on campus that maybe do not exist anymore, but people wanted to document them when they were here.

A: How do you determine what gets collected?

AN: We have a collection development policy that lays out that framework I was just telling you about. We [try] to collect from all the different groups of people that have been here and try to show a diversity of perspectives. There are certain things, like furniture, that are just too big for us to take. Even if there is a lot of historical value to it, we do not have the space within the archives to keep it. It takes more space to hold a single basketball than it does to keep a bunch of paper records.

A: What kind of historical documents do students interact with?

AN: I pulled letters from the very first president here at the University. This is from Wilbur Fisk. What I do as the archivist, but also what my student workers do, is help create inventories and rehouse records so they are easier to find. They’re described in a way that researchers can see what we have at a glance. We cannot digitize everything. It’s super time-consuming, and you end up taking up a lot more space within the digital zone, which also costs money. The paper itself is, for the most part, pretty stable. If you treat it nicely and have it in good folders and in nice boxes that are acid-free, they are going to last for a really long time. Some of these are from 1837. We put tissue paper between them to make sure they are protected. Some have little areas of weakness. You get to understand the material culture of it when you get to touch it and interact with it in person. You can actually see how it was folded. You can see how the piece of paper was the envelope itself. It was not just the letter. It gives a sense of the history of the University in a way that just seeing it online does not.

A: What kinds of student-created materials are in the collection?

AN: The Argus is the longest bi-weekly [college] newspaper that we know about, but there are lots of other publications that students have created over time. These are just some. This is one box of about twenty student publications that are zines, chapbooks, and journals of student poetry. These are some of the things that we have been trying to digitize, especially those of various student groups that used these types of publications to tell their own story. We digitized The Argus and the yearbook [Olla Podrida]. There’s one [journal] called Iahu; it was an early women’s journal in the late 1970s and 80s [during] the second round of co-education. It’s a way for them to tell their own story. That’s something we want to try to promote on the Internet and showcase what is there.

We have things titled Joy Buzzer, Jar, and Intercut, which I think is a film magazine. You get a chance to see all these different areas of campus and different time periods. You can see what was happening during the Civil Rights Movement and the protests of the 1960s and early 1970s. It’s a way for students to see that they are part of this community that has existed for a really long time. While things are different from what they used to be, in a lot of ways, they are very similar.

A: Do many students use the archives?

AN: We do just over 100 class sessions every year between [Head of Special Collections] Tess [Goodman] and me. That means about 40 to 50 use the archives in some way, shape, or form. Then we have students who come in and do research. We’ve had theses that have been written using our materials. It’s a really great idea—it’s a way to do unique and individual research without having to go far. It is all here. You do not need a class reason to come in—if you are part of a student group, or you want to learn about what it was like for arts on campus, or you heard [that] Joni Mitchell performed here at one point, all you have to do is email us. We will set up an appointment with you. We usually have students coming through our reading room every week.

A: What about photographs?

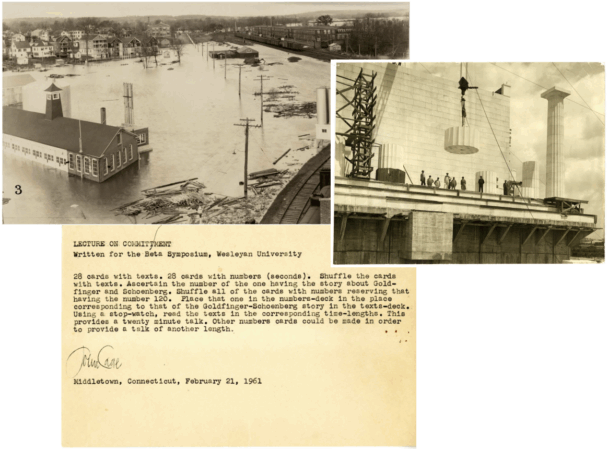

AN: [Here] is our largest collection of photographs [on campus]. We used to have a University photographer here on campus. These happen to be from the Wesleyan strike in 1970 for the National Student Strike, documenting campus life. You can see similarities to what is happening here on campus now, or how it is different. You get to see how the University has grown and evolved over time. You can see all the people on Foss Hill at one of the protests. It’s a way for not only current students to get a chance to see what is there, but also for alumni. I work a lot with the 50th reunion classes. They create a book to document what’s happened in the past 50 years since they were here. Some things you don’t realize how much has changed, and then you are like, “I know where that is,” or, “I know that window,” or you can see the field, or how buildings have changed. North College used to be a dorm. We have pictures of students sitting in their dorm rooms that are now a dean’s office.

A: Do you have a favorite item?

AN: One of my favorites is tangentially related to Wesleyan. We have collections by people who had some affiliation with the University. Henry Bacon was the architect of Olin Library and many buildings around campus in the early twentieth century. He was also the architect of the Lincoln Memorial. We have all the plans and a full run of the photos of the building of the Lincoln Memorial. Every day, they would take images from different angles. You can watch [through the images] the monument being built. Even the National Park Service doesn’t have those; we’ve been helping them fill in gaps in their collection.

A: What challenges do you think the collection is facing, looking into the future?

AN: We’re moving into a digital society. As everything is digital or online, how do we document those types of things? There is always a lag between when you get things into an archive from when it was created. People want to keep their memories with them. Usually, it is not until students or alumni are retiring or downsizing that they decide to part with some of these records. That’s when they come to me. Right now, that is still fairly physical in nature, but I am trying to think ahead about how to make sure that the generation now is able to, in 40 to 50 years, have the same access to images and what was happening here on campus as those that were here 40 to 50 years ago. It’s easy to lose digital files or photos. There are no descriptions associated with all the photos people have on their phones. We are trying to work more proactively with student groups to document things while they are here so we do not have as big of a lag time.

A: What is the best way for students to start exploring?

AN: Not everything is described in our online systems. Contacting me if you are interested in anything is the easiest way to find out if we have something. That’s the key for every archive out there. There’s always a backlog of things that have come in that we just have not been able to describe yet. We are constantly working on it, but we are not quite there.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Nancy Li can be reached at nli02@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply