Trio Globo less than sum of its parts

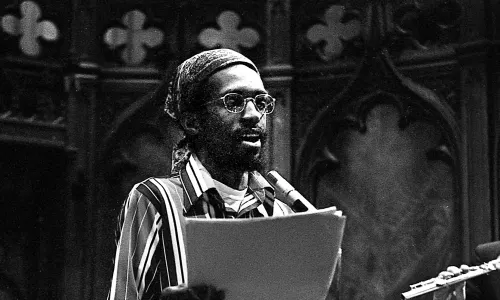

If you weren’t actually at the Trio Globo concert, you might very well think that I am playing the standard game of musical hyperbole, saying that the trio is composed of jaw-dropping virtuosos, who possess an ability to play that borders on the ridiculous. Unfortunately, the trio, composed of Eugene Friesen, Howard Levy and Glen Valez, seems to squander its abilities on music that never really delivers on its promise.

Levy led the ensemble on both piano and harmonica, sketching out the melodic space with doubled leads on both of his instruments. The interplay between the bent notes of the harmonica and the tonal clarity of the piano created a unique composite sound, warmer and better defined than either instrument alone.

Best known for the harmonica, Levy pulls a massive range of notes and chords from the simple instrument, re-imagining its fundamental capabilities. Weaving around Levy’s chordal structures, Friesen created a fascinating and often beautiful counterpoint. At times, he would pluck the cello like a bass, holding down the bottom alongside percussionist Valez. This allowed the group to groove straight out, transforming the ensemble into a kind of world beat jazz band.

Friesen also bowed his chords and melodies, adding a timbral elegance and broadening the group’s sound. In fact, a large part of the trio’s massive range can be attributed to his multi-faceted approach to the instrument.

Finally, Valez created the group’s rhythmic thrust, and was, by far the most impressive of the three. Holding down complicated polyrhythmic grooves with little more than a hand-drum and a cymbal, he played with masterful restraint, sketching out the rhythmic structure instead of drilling it into the music.

More than a glorified timekeeper, Valez fully contributed his own distinctive voice, adding a darting, powerful rhythmic counterpoint to the more melodic focus of the other musicians, which provided a sense of muscle that the music might otherwise have lacked.

Over the course of two hours, the three applied the full force of their virtuosity to a variety of styles, incorporating the influences of numerous musical traditions from around the world.

But, somehow, the concert didn’t really thrill. In and of itself, pure instrumental ability is never enough to ensure great music. Much of the time, Trio Globo was held back by a pedestrian compositional sense, one that skirted the boundaries of the soulful/jazzy/funky blandness beloved by formerly hip baby boomers.

While the arrangements were often fantastic—full of unexpected shifts and detours—they were built around melodies that blended together, dragging the tunes down with them. During a handful of pieces, the Trio embodied everything that its musicianship promised. They were at once tight and loose, the percussion and the cello creating a maelstrom of rhythm, while washes of piano and Levy’s astounding harmonica rode on top, melding into a joyful eruption of polyphony. Great as these moments were, they were sadly fleeting.

Trio Globo feels slightly less than the sum of its parts. For a group to work, the musicians within it must feed off of each other, coming together in mutual inspiration to create something independent, something with its own soul and spirit, something different than a mere combination of components.

If the musicians fail in this, the music easily relinquishes thoughts of greatness, slinking back into the merely good. For example, of the three best moments of the night, at least two were solo performances. In these solos, the musicians, particularly Valez and Friesen, transcended the rest of the concert, creating music that combined multiple traditions and formed a unique whole out of its composite parts. In doing this, they created something that was both new and great. More than anything else, it was these solo pieces that show how much further Trio Globo could have gone.

Leave a Reply