c/o Alan Chin/The New York Times

Early in the morning of Dec. 4, outside of the entrance to the New York Hilton Midtown, UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was attending an annual investors meeting when he was fatally shot by a suspect with a long, 3D-printed gun. Shortly after the incident broke, photos were released of the suspect, who was captured on a security camera checking into a hotel in an apparently charming and friendly manner, and his good looks sent a shock wave across social media.

While many harmless online jokes such as “I can fix him” quickly permeated cyberspace, others took to social media to defend the crime itself, citing anger at healthcare companies for their inhumane practices. As the media accused Luigi Mangione of the crime, social media erupted with celebration of the murder, public sympathizing, fan edits, and condemnation of New York law enforcement.

Of course, while much of this discourse was induced by outrage at profit-maximizing insurance companies, support was mobilized, not only through this capitalistic anger, but through the charming, handsome, and unassuming persona of Luigi Mangione. Though he is a UPenn graduate from an upper class family, Mangione attempted to portray himself as a martyr of capitalist greed in his manifesto—an image that was quickly overlooked when countless shirtless photos and miscellaneous selfies flooded social media.

Certainly, the fact that Luigi Mangione is a handsome white man captivated many people across the Internet. Suspects of color are often reduced to racial stereotypes when discussed on mainstream news outlets and online. In these cases, one’s race, in and of itself, becomes the proof of crime. In contrast, whiteness, in criminal cases, commonly invites speculation regarding the suspect’s mental health or criminal motives. Moreso, attractiveness can be an added virtue, with many presuming innocence and righteousness in more conventionally attractive suspects. And while this may be a socially created assumption, a recent study in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology found attractive defendants are frequently perceived as less guilty and receive more lenient sentences.

In Mangione’s case, his whiteness and good looks invited mass discourse and investigation into his motivations, tactics, and personal life—and many used this strategy to vindicate the actions for which he’s being tried.

While this bias has severe implications for the criminal justice system, the entertainment industry often exploits this conflation of good looks and innocence to form character arcs where an attractive villain has justifiable motives, often spurred by a series of traumatic events, leading to this unassuming, innocent protagonist to commit violent acts. This fascination with Mangione can be directly linked to this fascination with white, attractive criminals that has pervaded the entertainment industry.

While the cultural effects of Mary Harron’s “American Psycho” (2000) can consume a whole article, the popularity of Christian Bale’s Patrick Bateman, whose painfully handsome charm consumes the film’s screen time with his long, egotistical, yet skillfully violent monologues, is proof of this fascination. (While this movie seemingly satirizes our own views of attractive white criminals, film-bros frequently overlook this aspect.)

Other movies such as “Psycho” (1960), “Badlands” (1973), “Taxi Driver” (1976), and “The Shining” (1980) all use similar tropes of white male criminals, leading audiences to rationalize, empathize with, and pity the criminality of these characters. Recently, with the rise of biopics, we have seen this genre of true crime exploiting real-life criminal stories to capitalize on empathetic character development.

Using handsome actors to play the world’s most despicable killers, such as Ross Lynch as Jeffrey Dahmer in “My Friend Dahmer” (2017) and Zac Efron as Ted Bundy in “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” (2019), these films often sexualize and personalize these characters in a way that not only humanizes the criminals, but glorifies them to extremes where audiences view the character’s persona and attractiveness as the antithesis to their criminal behavior.

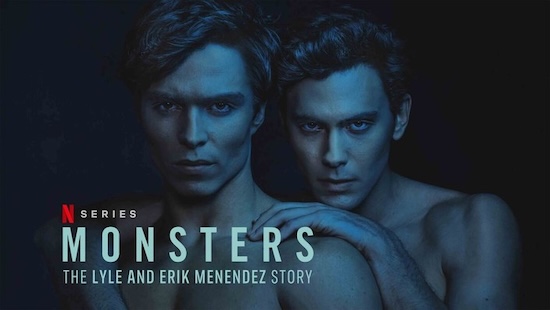

However, no piece of entertainment has exploited these tropes to the extent of Ryan Murphy’s series “Monster,” which recently portrayed the Menendez Brothers in the second season of the show, following heartthrob Evan Peters’ portrayal of Jeffrey Dahmer in the first season. Despite Murphy’s involvement in award-winning, yet controversial, shows such as “Glee,” “American Crime Story,” and “American Sports Story,” none of his work has been as reckless in its portrayal as “Monster.”

In both seasons, Murphy conceptualizes the plot with a singular question: “Are monsters made, or are they born?” However, with this, Murphy is using the idea of a monster, who is usually unattractive and grossly unkempt, to juxtapose this trope with handsome criminals, implicitly arguing for a polarity between these identities.

Both of these seasons first begin with the crime itself, then use all-too-predictable sympathy points to humanize the criminals, giving them an emotional struggle that attempts to discount the crime itself—often using hearsay to dispute their criminality. Despite heavy criticism of the show’s two seasons, Murphy has been unapologetic in his approach, which uses many differing (and unfounded) accounts of the events depicted in his shows to form what is referred to as the “Rashomon effect,” a term that points to the challenges of labeling direct responsibility on a character due to conflicting interpretations.

c/o Netflix

However, throughout this series, he strictly uses claims of sexual relations and sexual trauma to maintain a character’s “innocence.” Despite a common social conflation between attractiveness and innocence, as Natalie Issa argues, Murphy creates a relentless, but tiresome, investigation of criminality.

“[Murphy’s retelling is] so obsessed with the same question posed 30 years ago that it loses any perspective of its own,” Issa wrote in Deseret News.

Thus, if Murphy is not interested in arguing towards one perspective but instead exploring a summation of varying, publicized interpretations, what else is the show’s purpose besides glorifying the criminal?

With Dahmer, families of the victims were quick to denounce the show for its overt sexualization of Dahmer’s relationship with his victims; many critics also pointed out how the portrayal of Dahmer was too keen on justifying his backstory. With its focus on the Menendez Brothers in the second season, the show included scenes of sexual abuse from their father, which was unconfirmed in any reports or the 1994 trial of the case, and an incestuous sexual relationship between the brothers, which is—mostly—unsubstantiated.

In both examples, these criminals are reduced into primarily sexual beings, motivated and aggravated by such plot points—such that the character’s physical body and sexual desires become the show’s central plot. Perhaps, in the case of Dahmer, this allows for more sympathy to the victims, as if “it could have been anyone”, but these stories consistently frame the criminal’s sexual relations and trauma as a catalyst for their criminal activity. Highlighting these dubious plot points, the purpose of the show seems to glorify attractiveness, seduction, and trauma as if there are rational, or, at least, justified, means of murder.

When Murphy was questioned about the reason for including an unproven incestuous relationship in the “Monster,” the carelessness with which he frames the plot was clear.

“Some of the controversy seems to be people thinking, for example, that the brothers are having an incestuous relationship,” Murphy said in an interview with Deadline. “There are people who say that never happened. There were people who said it did happen.”

What’s most peculiar about “Monster” is that Murphy strictly uses recent events, and fictitiously glorifies them as if the witnesses are not living today and are unable to publicly denounce the show’s falsification. Not only this, but through this glorification, the popularity of Murphy’s show and ones similar—successful or not—forms a new, holistic view of modern criminality, its mode of operation, and its justification. While this may create a public discourse that is more sympathetic to the criminal justice system, the effects of glorifying white, often attractive, criminals is clearly evident in the case of Mangione.

As quickly as thirst traps of Mangione circulated the internet, jokes referencing Murphy’s fascination with this criminal prototype were persistent. Perhaps Murphy is, now, staring at countless photos of Mangione, as he writes his third season of the show: “Monster: The Luigi Mangione Story.”

Carter Appleyard can be reached at cappleyard@wesleyan.edu.