Partners in Data is a column written by Executive Editors Caleb Henning ’25 and Elias Mansell BA ’24 MA ’25. We are partners who share a love of data analysis—which includes tracking our dates through graphs—as well as writing. While we both have experience with data collection and data analysis, this column is exploratory and our methods will not always be robust. If you have any suggestions for quantitative topics related to Wesleyan that we can investigate, or if you’d like to see our data, please reach out!

As the spring semester kicks off, we’re all going through the familiar routine of buying new notebooks, reuniting with friends, and navigating the perils of drop/add. As data analysts who’ve heard the constant complaints of students struggling to get into the classes they want, we were interested in spending some time looking into just how hard it is to get into the classes you want to be in.

But the University, regrettably, does not have a beautifully organized spreadsheet with drop/add statistics (as far as we’re aware). So we collected our own data. Although we did not have time to look at all 666 non-POI classes on WesMaps, the course catalog, we were able to analyze numbers from the six departments with the most majors and the five departments with the least. We manually recorded the capacity, the number of seats available, and the number of pending enrollment requests for each class in these departments on the evening of Thursday, Jan. 23—a snapshot of the chaotic and dynamic process known as drop/add.

The six largest majors that we decided to include in our analysis were psychology with 270 students, economics with 265, government with 187, computer science with 125, film studies with 121, and English with 118, while the five smallest majors were dance with 9 students, classical studies with 12, Italian Studies with 12, African American Studies with 15, and religion with 15.

However, if you look at the Fall 2024 major reports, where we got our data, these are not actually the smallest majors. (That honor belongs to Global South Asian Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Studies, and German Studies.) We decided to exclude departments with fewer than five courses due to the small sample size, which may not have been the most statistically rigorous approach. Additionally, we classified cross-listed courses under their primary department listed in WesMaps to avoid double-counting courses. We quantified the demand for each class by adding the number of enrollment requests to the number of students currently enrolled and dividing the resulting sum by the total capacity of the class.

Now that we’ve gotten the methods out of the way, here are three takeaways from our analysis:

- Large departments have not adjusted the number of spaces in courses enough to meet high demand.

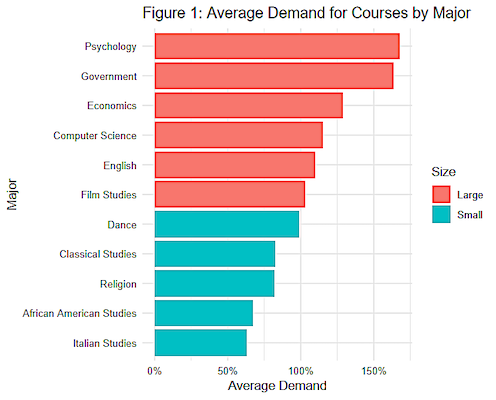

The average demand for courses in the six largest majors surpasses 100% (Figure 1), while smaller departments have an average demand of approximately 70%—except for dance, which is evidently very popular with non-majors. So if your drop/add luck has been poor, maybe try learning Italian or diving into African American Studies!

Psychology majors have it rough, with an average demand of 168% across courses. The introductory course for the major, “Foundations of Contemporary Psychology” (PSYC105), faces a demand of 270%, with 189 students competing for 70 seats. It doesn’t get much better once you’re in the major: Four psychology courses have over 200% demand, and almost every single course has more than 100% demand.

Government isn’t much better than psychology: It has an average demand of 164%, 6 courses with over 200% demand, and only one course where demand does not outpace capacity. Economics, on the other hand, isn’t as bad as it may seem: The department faces an average demand of only 129%, with only one course with at least 200% demand and 6 courses with less than 100% demand. Next time you hear an economics major complaining about how hard it is to get into their classes, remind them they don’t have it the worst! (We can say this because one of us is an economics major.)

That said, demand can vary widely between classes in the same department: Dance has an average demand of 99%, which encompasses courses with as little as 20% demand and as much as 212% demand.

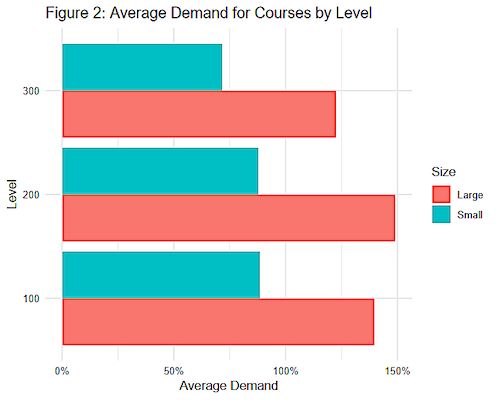

2. The level of the course doesn’t make as much of a difference in demand as you may think.

Before we looked into the data, we both believed that the introductory courses were the barrier to entry for larger majors: As long as you could make it past the first course, you would have an easier time with upper-level electives. Our analysis shows that this isn’t always true. 100-level courses in large majors have a demand anywhere from 27% to 270%, while 300-level courses in large majors have a demand between 25% and 237%. Smaller majors, on the other hand, have consistently lower average demand regardless of level.

So good luck to all in the most popular majors on campus—you’re going to need it.

3. Small departments are kept alive by non-majors.

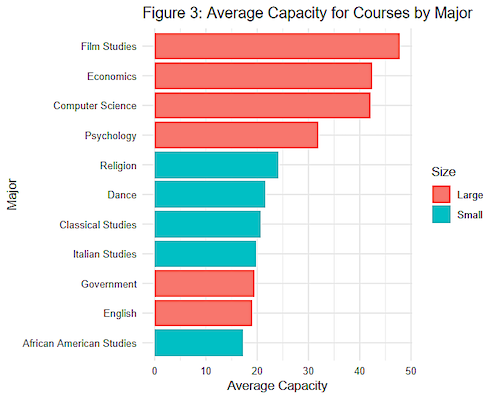

The three lowest levels of average demand sampled are 63% for Italian Studies, 67% for African American Studies, and 82% for religion. While these are much smaller numbers than the data for large majors, even small departments have some courses with over 100% demand. These classes are not filled with majors: Italian Studies and African American Studies only have 12 majors each and religion has 15. These are below the average capacities of 20, 18, and 24, respectively (Figure 3). This tells us that non-majors are an important part of small departments.

While these graphs show that drop/add isn’t always as bad as you might think, there is something sad about the data. Non-majors can browse through classes in small departments and get the well-rounded liberal arts education that we know and love, but it’s difficult to get into any courses—lower or upper level—in the largest departments on campus. There is one question the data can’t answer: How many students who are interested in psychology, government, economics, computer science, and English—but not committed enough to navigate drop/add—never get to take any courses in those departments because the demand is so high?

Caleb Henning can be reached at chenning@wesleyan.edu.

Elias Mansell can be reached at emansell@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply