Since its 2000 premiere on CBS, “Survivor” has been a smash hit. As one of the highest rated reality television shows in American history and still one of the most profitable almost 25 years later, the series is nothing short of a cultural phenomenon.

Each season follows the same basic premise: Around 20 contestants are split into two, three, or four tribes. Each tribe lives in a “deserted” camp (usually on a tropical island) where they must band together to build a shelter, gather food, and keep warm. In each episode, tribes compete in challenges for the chance to win immunity. Any tribe without immunity votes one of their tribemates off the island in one of the show’s trademark melodramatic Tribal Councils.

At around the season midpoint, the tribes merge and contestants compete for individual immunity. Any contestant without immunity, then, is vulnerable to elimination (except if they’re in possession of any of the show’s convoluted advantages). This continues until the final Tribal Council where eliminated contestants vote on which finalist should win. The votes are read and the winner is crowned “sole survivor.”

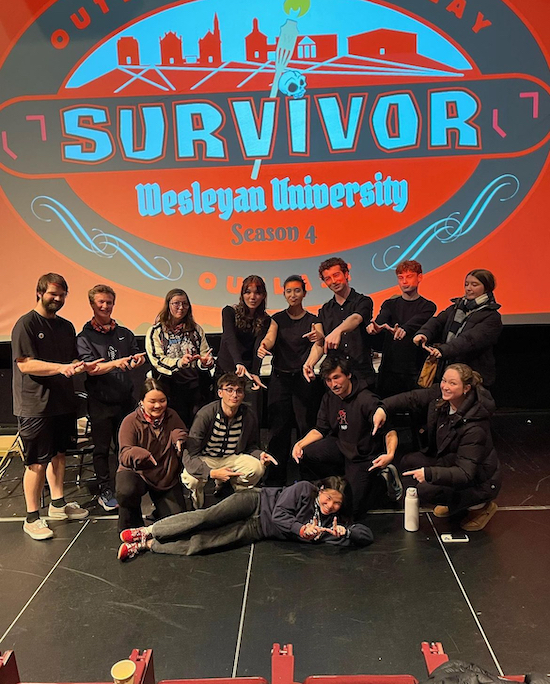

As “Survivor” continues to captivate millions of viewers across the world in its 47th season, the fourth iteration of Wesleyan’s version of the challenge-based program came to a close earlier this week.

In Spring 2022, a new student forum, led by Gabe Goldberg ’22 and Noah Olsen ’22 was introduced: “The Psychology of Survivor: A Dual Perspective Approach.” In this forum, students learned about the various concepts of social psychology at play in team dynamics that play out every season on the show. At the same time, they became contestants themselves, being separated into tribes, playing challenges, and voting their teammates off the figurative island throughout the semester. Jesse Herzog ’25, one of the original participants, explained that the group dynamics seen on the show and in the classroom have been a subject of study by social psychologists for decades.

“The Robbers Cave experiment is a really foundational study in psychology…that basically [demonstrated that] when you have two groups that are conflicting, they’re going to not like each other,” Herzog said. “If you have them work together, they will [start to get along]. That study essentially inspired ‘Survivor.’”

Herzog collaborated with other players from the original class to propose the student forum again in Spring 2024, spending the previous semester planning out a refreshed series of lectures, as well as new challenges and advantages for participants.

Wesleyan Survivor came back this semester, with Herzog leading it along with Susie Nakash ’26 and Sam Pohlman ’26. The coordinators wanted to be sure that this set of players got an authentic “Survivor” experience. They even left notes for players in the style of “tree mail” from the real show, which is the primary way that the television producers communicate with contestants.

“There’s no cameras or anything, but we go through the whole rigamarole of asking [the players] questions during Tribal and trying to get them to open up a little bit,” Herzog said. “[Outside of class,] we write tree mail every week, make and hide idols around campus, and have people send confessional videos to the [Google] Drive.”

Including these details as a part of the course has led to Wesleyan Survivor players referring to Herzog, Nakash, and Pohlman as their “Jeffs,” after Jeff Probst, the longtime host of the real “Survivor.”

Of course, Wesleyan Survivor works a bit differently than the acclaimed television program. Participants meet once a week, and, unlike traditional “Survivor,” each class session (except the first one) begins with Tribal Council. This nerve-wracking decision forces the losing tribe to vote one of their own members out of the game.

If voted out, a student still attends the forum but observes the following Tribal Councils as part of the group that will ultimately vote for the season’s winner. To say the least, for most participants, Tribal contains high, semester-altering stakes.

“[At] the first one, everybody was shaking,” Oliver Katz ’27. “Nobody was talking. As you get used to it more, the nerves go away, but it’s still pretty scary.”

Following Tribal, the class moves into the conventionally academic part of the forum, where the participants learn about psychological concepts such as social conformity and aggression. Students watch documentaries, view clips from real episodes of “Survivor,” and discuss the topics as a class. These “Survivor”-style confessionals serve as the forum’s weekly homework assignments, where players get the chance to apply the psychology concepts from lectures to their and their peers’ games.

“I find as we’re learning more stuff, I can see how this is applying to what I’m doing,” Terra Hoyt ’25 said. “And that’s always a cool thing to see that you’re actually applying what you’re learning.”

In addition, the videos allow the players to anonymously explain their current standing: who they’re aligned with, who they hope to vote out, any strategies/advantages, etc.

At the end of each class, the remaining participants compete in a challenge in their respective tribes. Ranging from word scrambles to plank-holding contests to navigating through the Wesleyan campus tied together and blindfolded, the challenges assure brief tribal immunity while additionally creating a collective goal and pride among tribe members.

Yet the time spent on “Survivor” does not stop when class ends or even once homework assignments are complete.

“Obviously it’s different than actual ‘Survivor,’” Ava Olson ’25 said. “You have a whole week to deliberate, talk about what’s happening.”

In the week before the forum regroups, many players gather with other participants multiple times to explicitly discuss strategy or even fake strategy. But setting up a meeting with someone does not ensure that you two are aligned—it can merely serve as a front.

“I can’t even keep track of all of the meetings that I have going on,” Katz said. “Everybody’s meeting with everybody.”

When participants see each other outside of the game in an unplanned fashion, there aren’t clear-cut instructions for the interaction. Because there’s a blurred distinction between campus life and the game, many participants wonder whether they should speak even implicitly about “Survivor” to their peers, for fear it could impact the game.

“I’ll run into people in the class in public, and it’s like, ‘How much am I supposed to be saying to you right now?’” Hoyt said. “There’s eyes everywhere.”

When it comes to navigating this complicated social aspect of the game, strategies have varied from player to player. While many chose to stick to a more active course, meeting with tribemates and assuring social connections, some laid low in an effort to dodge a target and others simply indulged in the fun of the class.

“It’s hard because the thing about ‘Survivor’ which has always been really interesting is there’s no foolproof strategy,” Eleanor Brown ’28 said. “A strategy that works in one season is not probably gonna work in the next season.”

While the participants enjoyed their semester playing Wesleyan Survivor, many agreed that engaging with the student forum fully required a high level of focus and effort.

“I feel like you have to have a certain level of intensity to be in [Survivor],” Clara Lewis-Jenkins ’28 said.

Yet it is this type of intensity that turns the game to such a bonding force. Even students that joined the forum with established connections and friends on campus found it enjoyable to be immersed in an entirely new group of people.

“Wesleyan is a super diverse place, and I think if you get stuck in one group, it’s hard to get out of it,” Katz said. “So it’s kind of cool being in a class where it was completely chosen at random, and I’m working with and am friends with people that I would not know otherwise.”

Players past and present agree, Wesleyan Survivor has created a new kind of community on campus, one that’s forged connections in unlikely places.

“It being senior year, I feel like I’ve been trying to either make new friends or reach out to people that I’ve kind of talked to or that I wave to but that I don’t really know,” Olson said. “But I think this has been a really good opportunity to just meet more people. I’ve been really thankful for that.”

Eliza Walpert can be reached at ewalpert@wesleyan.edu.

Sulan Bailey can be reached at sabailey@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply