In the week following Tuesday, April 23, the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery saw the final spread of senior art studio theses, an inspired compilation including paintings and sculptures, as well as vast displays and compact media. What becomes apparent through the extremely diverse directions taken by seniors within the University’s art studio program is the variety of sources that motivate its students to produce art. Each piece was a culmination of its maker’s artistic and personal development at the University and was crafted as a unique tribute to their time here. On Wednesday, April 24, friends, parents, and inquisitive patrons alike gathered to celebrate the senior creators.

In the week following Tuesday, April 23, the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery saw the final spread of senior art studio theses, an inspired compilation including paintings and sculptures, as well as vast displays and compact media. What becomes apparent through the extremely diverse directions taken by seniors within the University’s art studio program is the variety of sources that motivate its students to produce art. Each piece was a culmination of its maker’s artistic and personal development at the University and was crafted as a unique tribute to their time here. On Wednesday, April 24, friends, parents, and inquisitive patrons alike gathered to celebrate the senior creators.

Each artist drew on a unique idea, interest, or element of identity, and the result was a collection of very different works. Amy Limtrajiti ’24 used charcoal pencil, chunky charcoal, Sharpie, ink, and more to produce four large black and white drawings of birds, collectively entitled “Ways to Kill Plate a Bird.” She remarked that her choice of medium was motivated by a respect for the humility of drawing and the power in its down-to-earth nature. Most, if not all, of the birds are intended to no longer be living. While Limtrajiti expressed an openness to interpretation of her thesis, she explained that for her, this set of drawings was representative of a particular type of familial relationship.

“As the year progressed, [it] evolved to be zeroing in to examining family dynamics, particularly the suffocation that can arise from the sacrificial relationship between Asian/Asian American children and their parents,” Limtrajiti said.

While several of the birds appear to be mothers feeding their chicks, others are decorated with flowers or wrapped or hung with ropes. Using shading and erasure, Limtrajiti succeeded in producing a cohesive group of birds varying in scale, orientation, and state of life. She described the significance of portraying deceased birds with splayed or folded wings and limp bodies as graceful by appearing as necklaces or among blossoms.

“The intention of decoration—of adorning a corpse you killed with beautiful objects—is controlling and against birds’ natures, but it can still ultimately be considered an act of care,” Limtrajiti said. “Even though it’s a twisted love, it’s love nonetheless, but one that is undoubtedly harmful to the subject.”

c/o Langley Maciejewski

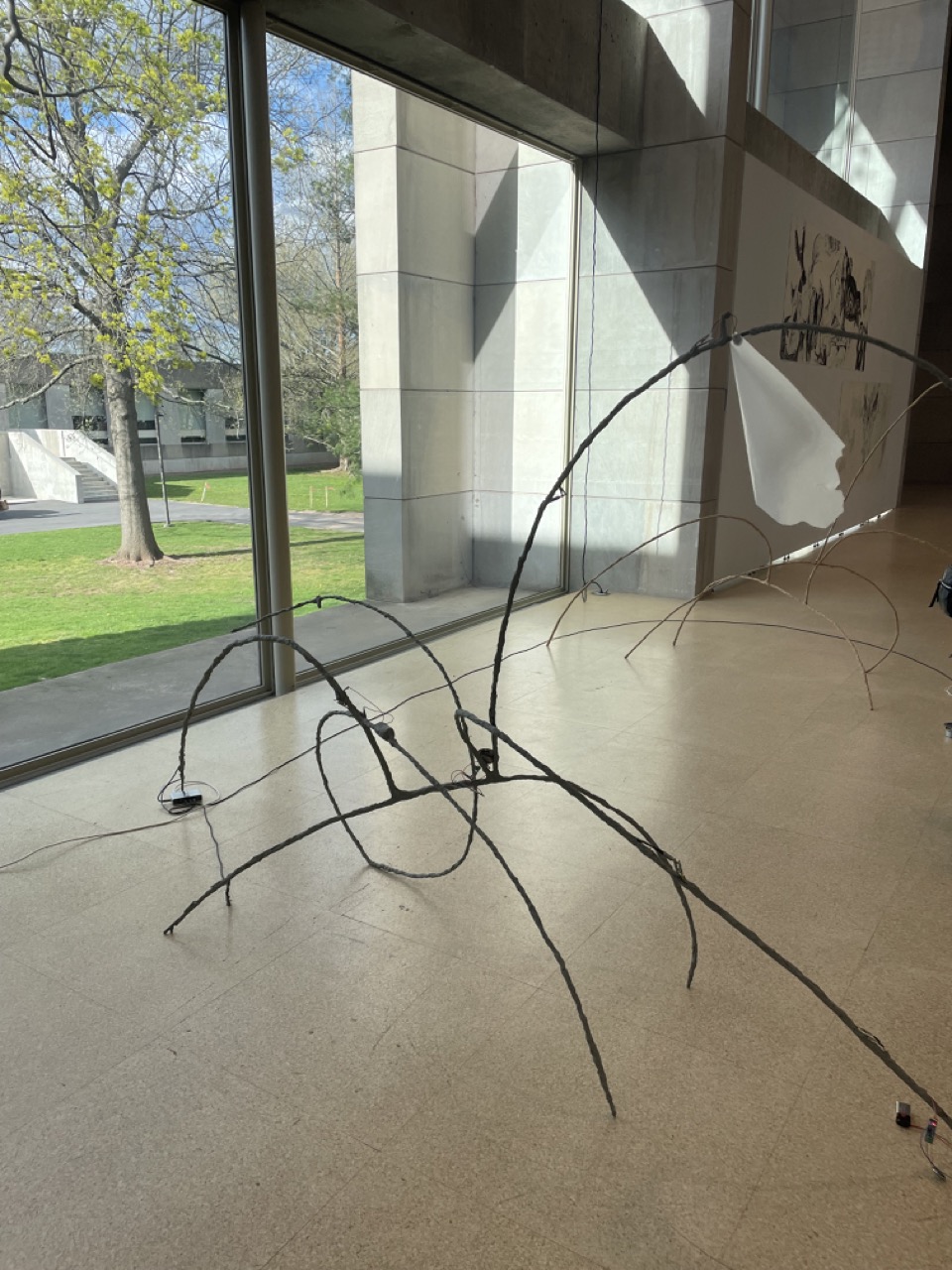

Limtrajiti’s beautiful work was located in the large main room of the gallery, next to “Talks in Circles” by Aidan Jelveh ’24. Jelveh’s thesis project consists of a variety of visually intriguing sculptures and other items. The two most captivating of these pieces were abstract, spindly, vibrating sculptures made from wire and clay that Jelveh gradually scaled up on the journey to exhibition week. With motors and audio electronics connected, the thin structures emitted noise and twitched intermittently. This constant subtle movement was inspired by the modern human dependence on technology.

“I was also interested in digital media and our attachment to it today,” Jelveh said. “How people like myself will spend hours scrolling or can’t walk around without music. I always have to have something going on, some sort of stimulus. So I wanted everything to be tweaking out and moving and reacting to itself.”

Among other components, on the wall across from the tweaking wire structures were a trio of small photographs obscured by opaque plastic boxes. They serve as a reference to the origin of Jelveh’s personal reliance on technology.

“The obscured images on the wall are selfies of myself from when I was 11 to 13,” Jelveh said. “In that piece, I tried to establish a connection to when I started getting really attached to technology as an extension of my body and mind.”

On the whole, Jelveh’s was one of the most fascinating pieces of student art I have seen, and many other patrons perusing the gallery spent time slowly moving around and attempting to absorb and interpret the significance of its different elements.

Backtracking from the central room of the gallery, I found myself admiring “Brain Itch” by Sarah Seabright ’24, and the title of the thesis instantly drew my attention. This thesis consisted of three brightly colored square canvases rotated against a large wall and one black and white, more dystopian-looking piece of the same shape rotated along the wall facing the other three. When I turned to examine the entryway positioned between the opposing walls, I found an intricate collection of vibrantly colored and beaded records. Along one of the first walls on the way into the gallery was a description of the internal motivation behind Seabright’s thesis.

c/o Langley Maciejewski

“Since I was two years old I have stumped medical specialists,” Seabright wrote in the description of the exhibit. “As I got older, seemingly disconnected symptoms started showing up. Each doctor tried to fix the individual part of my body that was failing. My [instinctive] reaction is to fight. To fight for my body to get healthy. To fight against my pain. To fight to be heard. It is [exhausting] to fight every day, and depletion and anguish are formidable and relentless opponents. Art is an escape from the fighting. I make art to control something, and my work is a log of the times I was able to have bodily agency and mental relief.”

Seabright could not be reached for further comment, but the unabashed use of color in the thesis and the number of pieces included is a testament to Seabright’s strength in channeling the pain of a plethora of conditions and diagnoses into a powerful means of artistic expression. Truly immersive and lively, “Brain Itch” was a clear ownership of one’s self and artistic creativity as a means of expressing perseverance and identity.

Between Seabright’s and Jelveh’s works hung the collection of 23 paintings on wood, collectively entitled “Junto a ti, buscaré otro mar,” by Luz Celeste Rivera ’24. These paintings varied in size and portrayed warm, still-life familial scenes, like a parent playing on the floor with their toddler, celebrating a child’s birthday surrounded by loved ones, and a kid on a knee.

“I had preconceived notions about what a thesis should be—a typical gallery installation that exemplifies one’s talent—influenced by my art history background and a desire to be taken seriously by my white peers,” Rivera said. “However, during a conversation in my senior seminar course, I realized that I wanted my family to be proud of my work above all else. This revelation led me to make my family the central theme of my thesis. I collected old family photos during winter break, selecting ones which represented key aspects of my childhood and Hispanic identity.”

This work felt like a personal window into Rivera’s creative intention, and upon hearing from them, it became clear that the materials used in the pieces also carry a meaningful significance.

“When I started painting at the end of the fall semester, I couldn’t afford oil paints, so I used cheap acrylic paints I had at home,” Rivera said. “I also used scrap wood from the woodshop as my canvas. I’m not embarrassed about using these low-cost materials, and they became part of the point of my work. Using inexpensive materials helps convey the themes of social class and Latinidad that would be lost using higher-quality supplies.”

c/o Langley Maciejewski

Aside from being drawn in by the intimacy of the tender images that Rivera chose to depict, the different sizes and shapes of wood used were also visually intriguing, urging the patrons of the gallery close to the display, craning their necks to look at the pieces located higher, like the painting of two women in dressed white embracing, and leaning to look at the mustachioed figure in the green armchair at the bottom of the display. A loving compilation of meaningful moments and representations of family, Rivera’s “Junto a ti, buscaré otro mar” was a skillfully and tenderly curated collection of works.

Although located in the first room to the right in the gallery, “No Curfew” by Zach Murgio ’24 was the thesis I viewed last on my way around the exhibition. At first glance, I could not tell what the colorful pieces were on the two tables in the middle of the room; wooden clothespins, seashells, and plastic blocks of different shapes and colors, among other items, were arranged in what looked like a miniature model of a park. Sure enough, Murgio’s thesis was inspired by this particular type of public space.

“Today, curfew ordinances, loitering laws, and physical design features exclude teens from gathering in public parks and squares, leading to serious consequences,” Murgio said. “It is an essential in adolescent psychological development for teens to interact in public spaces. Adolescents need spaces to hang out and socialize, unrestricted and unregulated, in order to grow into meaningful and productive members of the community.”

c/o Langley Maciejewski

Using both original 3D-printed shapes and everyday objects (including a mustard packet and a COVID-19 test), Murgio designed a game for teens that allowed them to design a park. The idea was for them to create a space for themselves—in particular, one that they are often excluded from—as Murgio researched, compiling lists of these laws in major U.S. cities to illustrate the need for these spaces for young people. By creating a physically interactive project for his thesis, Murgio both allowed high school teens to create their ideal public space and engaged them in his art and in the idea of autonomy and community-building.

On the whole, the final week of senior art studio theses for 2024 brought a wonderful variety of inspiration and displays by University seniors to the Zilkha Gallery. What made this compilation of projects so special was that each senior had the opportunity to present an element of themselves and their unique perspective of and vision for the world, and I am so grateful to have gotten the chance to view this group of talents. Each piece was a culmination of their journeys as artists both before and at Wesleyan, a place that has provided a unique path for all. It has also made all the difference for many, like Limtrajiti, who shared with me that her path through the University was not always geared towards art, but eventually it brought her closer to a passion she could not ignore.

“I tried everything I could to avoid accepting that art was the only thing I wanted to do,” Limtrajiti said. “I had a really tough time with it and took a year off to sort things out and ask myself what I really wanted—apart from what people always told me I should want. I realized that it was the thing I tried so hard not to love but ultimately do.”

Langley Maciejewski can be reached at lmaciejewski@wesleyan.edu.