c/o Carolyn Neugarten

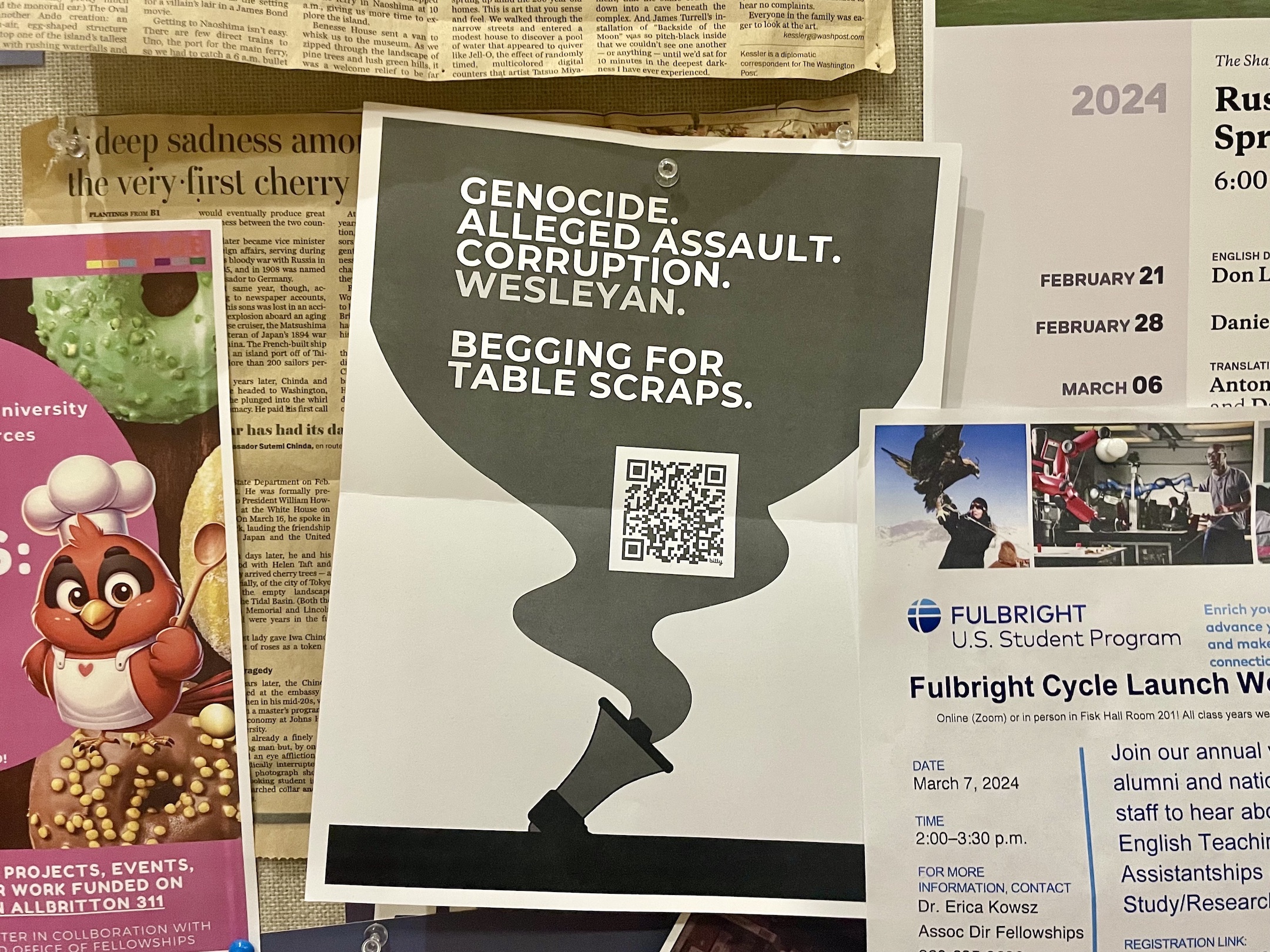

The work of over 30 students, the words of 15 interviewees, and more than 15 hours of recordings went into “Begging for Table for Scraps,” a student-produced zine about the power structure of the University’s upper administration distributed on Feb. 24, 2023. Compelled by issues ranging from the University’s investment portfolio to the fossil fuel interests of trustees, the writers, illustrators, and researchers aimed to scrutinize the University’s current key players and combat what they view as a decline in campus activism after the COVID-19 pandemic. The sensitive nature of the publication prompted the writers to remain anonymous and to be vigilant about avoiding surveillance.

Three students, who took on much of the editing, writing, researching, and layout, as well as the distribution of the zine, requested to remain anonymous for this article, and will be referred to henceforth as Students A, B, and C.

“Obviously we know what can come out of writing something like this,” Student A said. “There are legal implications [and we] may be liable to be expelled.”

Fearing repercussions, the students took care to evade University surveillance methods and embarked on the research project, which turned out to take five months. They initially did not plan to produce a publication of the zine’s scale, starting out with the goal of focusing solely on the board of trustees.

In late October 2023, Student B became interested in the operations of the Wesleyan board of trustees following protests about the University’s ties to oil companies, as well as the Title IX complaint against John B. Frank ’78 P ’12. The student also noted that the board seemed generally absent from on-campus discussions prior to these events.

With a burgeoning interest in the board of trustees, Student B obtained old issues of “Disorientation,” a student publication that aims to help students navigate institutions at Wesleyan, and conducted online research in late October before sharing their findings with a friend. At that point, the two realized that their research could encompass institutional culture beyond the board.

“I brought it to [Student A] in October and we sat down in my dorm for a good two to three hours, just planning the bare bones of what [the zine] would become,” Student B said. “A lot changed since then, but the interview questions were made that night, and the main research questions.”

Interviews began in early November, totaling over 15 hours of recordings. The students utilized connections when possible, and cold-emailed faculty, staff, students, alumni, and others affiliated with the University.

With the interview recordings complete, the students began outlining articles for the zine, focusing on concision. Once the student body returned to campus for the spring, the team intensified their work, writing nearly an article a day. Most articles were completed during late January and early February 2024, with the bulk of editing occurring in mid-February.

“We had a lot of articles that had to be moved and scrapped,” Student B said. “What we originally wrote was 60 pages…. We were spiritually crying a lot because we had to edit and cut so much.”

The students then coordinated layout and design for the zine. Students A and B set up a table in Exley, where the zine attracted multiple illustrators—who initially did not know what they were illustrating for—and the students ensured that the zine would be published before the March 5 board of trustees meeting.

Paper copies of the zine were distributed around campus on the morning of Feb. 24, after the students worked to document locations not covered by school security cameras.

“When we actually went to put the zines down, we had to make sure no one was watching,” Student B said.

The zine was also published in a digital format via Weebly, coordinated by Student C. The website has had over 5,000 visitors.

The student zine creators were concerned about the possible disclosure of their and their sources’ identities, and of the possibility of someone alerting the administration of the operation prior to the zine’s official publication.

“Basically, we made sure the least amount of people possible knew about the zine before we went public,” Student B said. “We wanted to make sure no one was on to us and what we were doing.”

Obtaining sources was a difficult task; many key informants, including trustees and Wesleyan faculty, were concerned about the security of their jobs and reputations. According to Student A, alumni perceived the effort as a smear campaign and were concerned about maintaining their relationship with the University. Every source referenced in the zine spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“We started reaching out to people,” Student B said. “We would say ‘Hey, would you be interested in talking to us about power relationships at Wesleyan?’ I don’t know how many dozens of emails we sent out over the course of months.”

Only the zine’s two head editors, Students A and B, have complete knowledge of source identities. In their internal documentation, interviewees are referenced by initials rather than by name. The students also used multiple encryption technology and the instant messaging app Signal, and deleted all logs after the zine’s publication.

“Those sources are going to die with us,” Student B said. “The only way that they can be found out would be if they can track down who we reached out to, and who we could have had contact with.”

To ensure even more layers of privacy, the writers only shared information and contacted one another through non-Wesleyan Google Suite accounts, and with private cellular service rather than the campus Wi-Fi. They checked classrooms for recording devices and cameras before holding meetings there.

“Universities are worried about student organizing to the point where…it is not a far jump to be concerned that the leaders of this institution are going to employ [extreme] types of surveillance tactics,” Student A said. “They are actively expanding surveillance on campus. So we’re just covering all the bases.”

According to Chief Information Security Officer Joe Bazeley, there are approximately 150 to 200 surveillance cameras on the University’s campus, all in public areas. Public Safety (PSafe) could not be reached for comment on the locations of these cameras, how security tapes are stored and monitored, or whether future cameras will be installed.

Classroom recording devices are distributed in designated “Zoom Rooms,” which allow classes to be streamed and recorded in real-time. The recording, file transfer, media preparation, and distribution is automatically uploaded to Moodle for the associated class. These Zoom Rooms are largely concentrated in Exley Science Center and the newly renovated Public Affairs Center. Other rooms in the Allbritton Center, Boger Hall, and Fisk Hall are equipped with an HD camera and a table microphone.

The ITS website claims that all classroom recordings are scheduled at the beginning of the semester or done on an ad-hoc basis, and there is no spontaneous recording outside of those prescribed times.

“My understanding is that [classroom recording technologies] are tied to remote or hybrid instruction and are only active when Zoom is being used,” Chief Information Security Officer Joe Bazeley wrote in an email to the Argus.

As for access to student Google Suite accounts, University protocol ensures that student account information is provided only in certain rare cases. If an individual seeks to access a student account, consent must be given from Chief Administrative Officer Andy Tanaka ’00, Chief Information Officer Dave Baird, and Vice President for Student Affairs Mike Whaley. Approved requests then go through Bazeley.

Full access to an individual’s Google Shared Drive is not provided. Only copies of files that match the prescribed search terms are shared, and all other files are kept confidential.

“I can’t think of any times in the almost five years that I have been at Wesleyan when I was asked to provide information from a student’s account,” Bazeley wrote. “The dozen or so times I’ve run this process, it has been to locate files and emails from staff members who have left the university without providing necessary content required for the operation of their department.”

The University’s on-campus Wi-Fi network, eduroam, is available to all students, faculty, and staff. The zine writers and other University students expressed concern about what information the University can access, particularly regarding students’ online activity.

For the University to investigate the internet activity of an eduroam user, relevant logs would include Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) logs; Domain Name Service (DNS) logs; and wireless access point attachment logs, called “Nyansa logs” by ITS, since Nyansa is the software the University uses to manage the wireless network.

DHCP logs assign IP addresses to devices and thus allow them to stay connected to WiFi; they are stored for 365 days. DNS logs, which record the websites visited by a user, are stored for three days.

“We intentionally only store 3 days of [DNS] logs to try to balance how helpful they are when troubleshooting issues…against protecting everyone’s privacy,” Bazeley wrote. “A list of all of the websites that an individual accessed is personal and should be kept private.”

The only time these DNS logs were accessed during Bazeley’s time at Wesleyan was connected to a lawsuit filed against the University. ITS’s searches were limited to Moodle web pages and the timeframes these web pages were accessed.

Nyansa logs are stored for 14 days and show what access point a device is connected to, and when that device moves from one access point to another.

“In my time at Wesleyan I have used the Nyansa logs 3 times to attempt to locate students, and for each of those times it was because Public Safety had received a report that the student might be considering self-harm and the student was not responding to phone, text, or email,” Bazeley wrote.

With the Nyansa logs, Bazeley attempts to identify an approximate area where the student might be, such as a section of a University building, so that a PSafe officer can go to that location.

Other than these prescribed instances, Bazeley assures that the University does not go through private student information contained in WiFi logs.

Even in the weeks after publication, the zine writers are concerned about maintaining their anonymity. If the writers are identified, Student B compared the possible repercussions to a falling house of cards: because information circulates so quickly on a campus of Wesleyan’s size, the ability to track down who talked to whom and when becomes an exponentially easier task as more people are revealed.

In two or three years’ time, the makeup of the University will change so much that it will be difficult to identify who wrote the zine. But until then, they remain cautious and vigilant.

“We do not have the legal [means] to go up against people like Roth or Frank,” Student B said.”We are trying to coordinate legal support.”

Even so, the students are proud of the work they have done, and hope to see a continuation of their work through future on-campus activism.

“It really feels like we got away with murder,” Student B said. “Except…we didn’t actually kill anyone.”

Carolyn Neugarten can be reached at cneugarten@wesleyan.edu.