Senior thesis season is now well underway, and with it comes a new batch of exhibitions to the Ezra and Camille Zilkha Gallery every week—the products of massive amounts of creativity and dedication from artists now in their last few months at the University. In this third week of exhibitions, the works were evenly split between exploring the possibilities of two dimensions and three. Yet even in the non-sculptural works, there was a distinct attention to texture, which struck me as the unifying factor that for these exhibitions.

c/o Louis Chiasson

These artists’ keen eye for texture was evident from the very first exhibition I walked into at the reception on Wednesday, April 10: “Model Collapse” by Emlyn Mileaf-Patel ’24. The predominant art form represented in this exhibition initially seemed to be photography. However, interspersed with glossy prints, were smaller tablets, some seemed to be made of plaster, while others looked like stained glass, all imbued with patterns that, to different extents, resembled human forms. Upon talking to Mileaf-Patel, I realized that, despite appearances, every piece in this collection was connected to the practice of photo-making.

“It’s a variety of different mediums,” Mileaf-Patel said. “There’s eight digital photographs, four of which are digital infrared photographs, there’s a bunch of darkroom prints which are anonymized film portraits that I put back onto film, and then there’s sculptural works which are extracted depth-maps [an image indicating relative distances of objects from the camera] from photographs. So it’s all based in photography.”

Revisiting the pieces in this exhibition with that context in mind, I noticed that, through layers of distortion, I could still identify the elements of humanity that shone through potentially inscrutable blocks, much like experimental filmmaker Phil Solomon’s works with degraded celluloid. With the more straightforward photographs, the opposite was occasionally true. Certain photographs were spotted with what looked like beads of light, abstracting their subjects and making the images look almost pointillistic. With this exhibition, Mileaf-Patel intended to push photography as far away from documenting the real as possible, while still maintaining its essential properties.

“It’s supposed to be exploring information and compression and imbuing indexicality into forms of photo-making,” Mileaf-Patel said.

In the Zilkha gallery’s main hall, the first things that caught my attention were the curious sources of light hanging from the ceiling: a dozen or so multicolored orbs. Each was shaped like a gemstone and made of fragile-looking material. This light was the centerpiece of “Reimaging Algae” by Sasha Detiger ’24. The exhibition also included a collection of vials and materials precisely displayed on the wall like a surgeon’s tools. Her piece’s title speaks to her use of the eponymous natural material.

In the Zilkha gallery’s main hall, the first things that caught my attention were the curious sources of light hanging from the ceiling: a dozen or so multicolored orbs. Each was shaped like a gemstone and made of fragile-looking material. This light was the centerpiece of “Reimaging Algae” by Sasha Detiger ’24. The exhibition also included a collection of vials and materials precisely displayed on the wall like a surgeon’s tools. Her piece’s title speaks to her use of the eponymous natural material.

“I was working on creating a material that was 100% biodegradable, and I worked with agar, which is a powder derived from red algae,” Detiger said. “I cooked it down and worked with a bunch of different bio-recipes and did some research until I landed on a material that I felt like was unique and different from others that I had seen. I used all-natural pigments and fibers to create the material, and then from there I wanted to create a lighting installation because I felt like the light really highlighted the material in a really interesting way.”

She was right. The diffuse light that emanated from the orbs was warm and inviting, and I could only imagine what it would look like in a dark room. Seeing the orbs themselves alongside the materials that created them, it became clear that making this piece meant curating what the natural world has to offer.

“I felt like a lighting installation was almost like a manifestation of my material research that I’d been doing all year,” Detiger said. “So I created these orbs in different colors using natural pigments like red beet powder, turmeric and green earth pigments to create these luminous orbs.”

The next exhibition on display was one of the more disconcerting ones: The textures of “Darning a Soul” by Willow May Frohardt ’24 were ragged and blotchy, alternately looking like film grain and blood splatter. Some of their drawings were abstract visions of violence that wouldn’t feel out of place in a “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” book. Others were much more precise works of almost photorealistic craftsmanship, though those drawings too showed bodies morphing into one another and contorting in unnatural ways. Scattered throughout the drawings were images of children, which Frohardt identified as central to the pieces.

c/o Louis Chiasson

“The main goal with my work was to explore my relationship with my childhood and my childhood self as it’s influenced by gender identity and mental health stuff,” Frohardt said. “All the kids you see are me from family photos and family photo archives.”

The mixture of materials—felt-tip pen and oil stick—and collision of memory and likeness with abstract fantasy and art-historical influence made for a powerful collection of pieces, a perfectly executed experience of ever-metamorphosizing visual unease.

Dylan Ng ’24 titled his exhibition perfectly: “A Demonstration of Care” is exactly what his eight gigantic oil paintings evoked. On each canvas, there was one or several people portrayed in vibrant color, depicted not realistically, but in a way that made it clear that finding the right colors and distortions for these people brought Ng a lot of joy.

“[Some of them are] my family, which is really fun,” Ng said. “All oil paintings. It was a fun process, just painting my family. They had no idea about it so it was just cool seeing their reaction with everything. Some of them are my roommates, and [one is] my grandma playing mahjong with her friends.”

Ng was modest in explaining his intentions behind the piece, but it appeared that this project was demonstration of care for those he loves. Everything from the way he talked about the paintings to the wide array of colors indicated that he derives joy from using his talent to honor those who have inspired him.

“I worked from photographs,” Ng said. “I took all these photographs and tried distorting them a little bit and then painted them the best I could, in a way that felt genuine and intimate and nice.”

c/o Louis Chiasson

Like Detiger’s project, the last piece in the main hall was also concerned with controlling light. “Solar Veil” by Emma Wilson ’24 had three components: a minimalistic diorama of the outside of a building, a large-scale version of blinds that appeared to be in the windows of that diorama, and cryptic printouts that seemed to indicate the location of the sun. As it turned out, this piece straddled the line between being art and architectural design.

“My thesis was centered around developing a second skin facade system to wrap around pre-existing buildings,” Wilson wrote in an email to The Argus. “The idea was to develop a system that would help shade the building from direct solar radiation during peak hours, while letting in sunlight during other times.”

The piece poses an elegant, aesthetically appealing answer to the question of energy conservation.

“The facade system helps to regulate the inside environment of buildings that currently spend a lot of energy and money attempting to do it on their own,” Wilson wrote. “The decision to use fabric was driven by the excitement around the possibilities it presented to experiment with shape and form.”

c/o Louis Chiasson

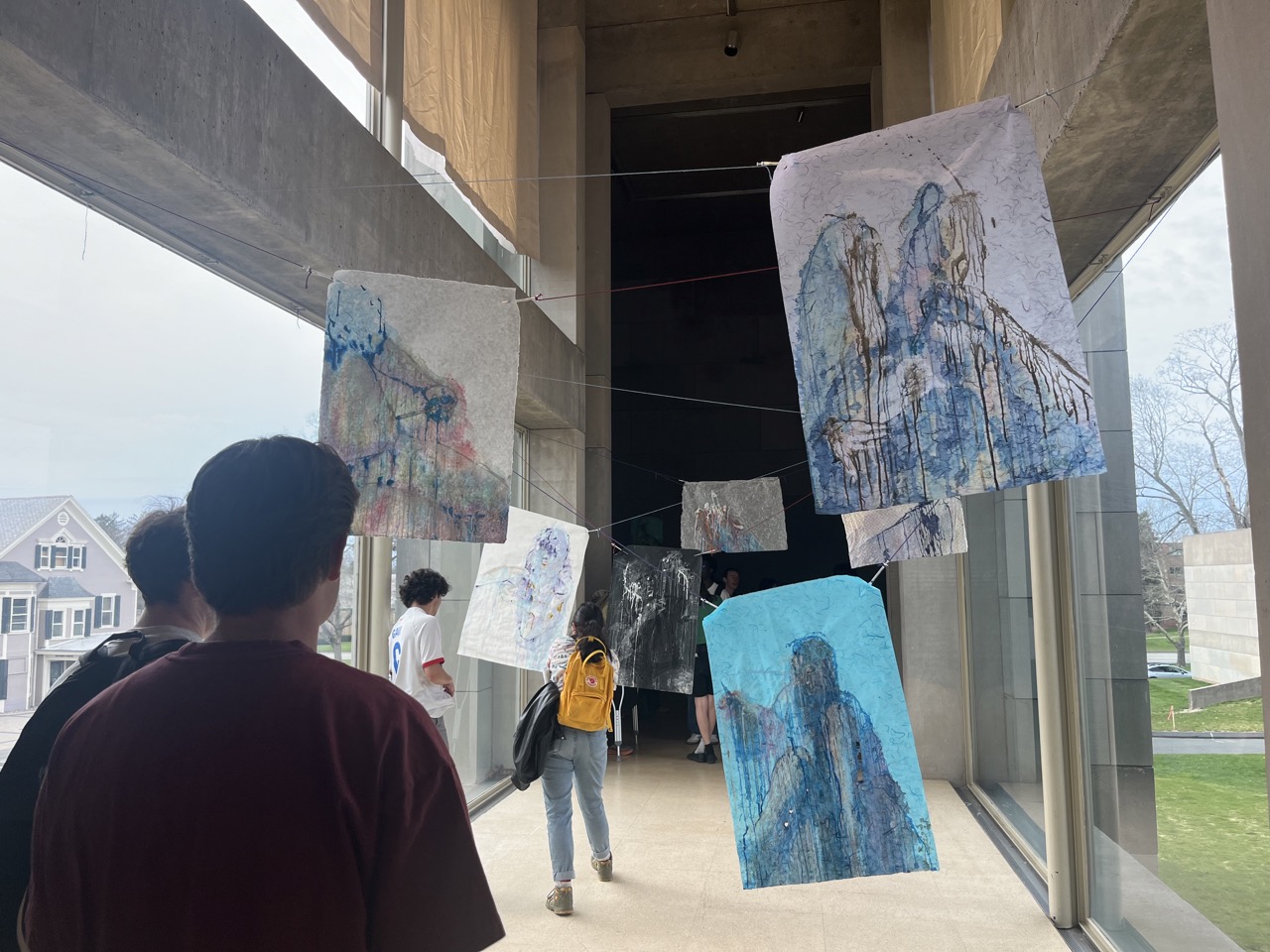

By far the most immersive piece in the gallery during this round of exhibitions was “Transition Kairos,” a multimedia installation by Alex Weidenfeld ’24. Situated in the hallway and adjoining exhibition space of the Zilkha Gallery, Weidenfeld’s piece consisted of abstract self-portraits in multicolored ink strung up all along the hallway, leading to three monitors playing avant-garde animated pieces that made use of Brakhage-esque overlays and editing techniques. Images of needles, some clearly visible and some distorted, recurred in the videos, alongside strikingly personal text that displayed messages like “my pain is love” and “mutilate me… I need it… I want it.”

“‘Transition Kairos’ is sort of an exploration of how my medical transition has influenced my relationship to the passage of time,” Weidenfeld said. “Even the title ‘Transition Kairos’—kairos, in modern Greek, just means weather or time, but in ancient Greek it has this connotation of time in a qualitative sense, as opposed to kronos, which is like clock time, time that’s counted, that time itself is an experienced, bigger force than you can really put a name to.”

This hyper-specific subjective experience of time was the throughline between the portraits in this exhibition.

“I created little self-portraits by drawing ink into my injection needles and spraying them at the portraits,” Weidenfeld said. “The reference photos for them are all of me taking my weekly T shot, but I had friends document it at different points during my transition. So even though it’s a timeline out of order of me doing the same thing, I look like a different person because these are six months apart from each other.”

The animated pieces, which Weidenfeld explained came out of extensive zine-making experience and his love of printmaking, used the feelings he associates with different color schemes to represent different factors of his emotional experience.

“The videos are sort of a color-based breakdown of dichotomy,” Weidenfeld said. “There’s this sort of red/black color palette, those are my positive colors, my really strong-feeling ones, and then the other one’s this really pale, pastel beautiful one—not that the other one isn’t beautiful—those are just me writing terrible things I think about myself, that’s my self-destructive palette.”

All of these feelings existed for the artist under the omniscient hand of time, and Weidenfeld felt that Zilkha was a fitting location to grapple with time’s celestial quality.

“I’ve always felt like this is kind of a cathedral space,” Weidenfeld said. “I feel like time is God. Time is God and God is time, and transitioning is this weird thing where I’m menopausal and pubescent and 22 at the same time, and I don’t know how to make sense of it but I’ve also been given this life reset button. And I don’t really know where it’s going, and I feel like I’m just this suspended body that’s really confused, and creating myself through art. So it’s a sort of self-reflexive process of just…doing personhood.”

The excitement and passion of Weidenfeld’s words indicated that the process of putting together this exhibition was deeply cathartic. Keeping with his skepticism at decisive beginnings and endings, it didn’t feel like a final statement on the artist as a person. Rather, it was a cataloging of his story so far, of feelings so overwhelming that they make finite time feel infinite. It was terrifically moving.

Together, these six exhibitions represent a survey of questions we’ll never answer: how to relate to nature, to images, to those we love, and above all, to ourselves. Leaving the Zilkha Gallery after the reception that day, I was struck by how clear-headed these artists were with their intentions, and how successfully they were all able to translate unsettled questions and feelings into works that were beautiful, even if the feelings themselves are not.

The fourth week of studio art thesis exhibitions goes on display in the Zilkha Gallery Tuesday, April 16, with a reception for those artists being held Wednesday, April 17 from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Louis Chiasson can be reached at lchiasson@wesleyan.edu.