What is the uniform of a hero? In ancient Sparta, it was a chest plate and a plumed helmet. For James Bond, it’s an iconic black suit-and-tie ensemble. However, in the modern day, particularly within young adult (YA) content, the hero’s uniform has become homogeneous: heroes wear light blue or navy blue collared T-shirts.

What is the uniform of a hero? In ancient Sparta, it was a chest plate and a plumed helmet. For James Bond, it’s an iconic black suit-and-tie ensemble. However, in the modern day, particularly within young adult (YA) content, the hero’s uniform has become homogeneous: heroes wear light blue or navy blue collared T-shirts.

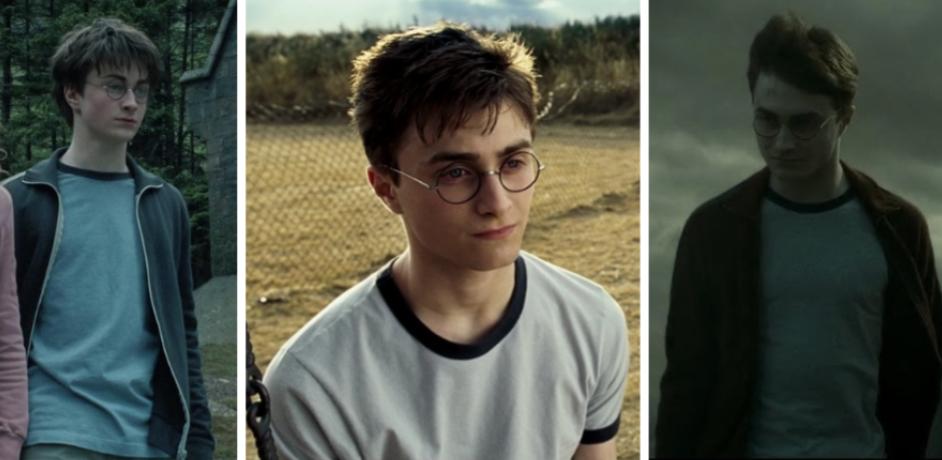

For years, in fandom spaces, posts have circulated poking fun at Harry Potter’s tendency to wear the same light blue ringer T-shirt in all eight films. Seemingly, after its first appearance in “The Prisoner of Azkaban,” costume designers decided it was a suitable outfit for their protagonist. Prior to the franchise’s third film, Harry was primarily pictured in his Hogwarts uniform. Costume designer Jany Temime addressed this change in a 2017 interview, stating, “I thought they should look normal, that they should look like normal kids.” That’s exactly what the blue shirt is: a normal outfit for a normal person whom audiences can root for, relate to, and project their fantasies of adventure onto.

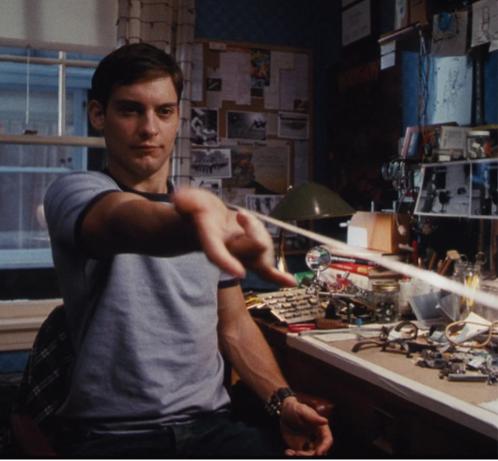

Many other designers agree. In Tobey Macguire’s iteration of the Spider-Man franchise, Peter Parker can be seen wearing this same blue ringer shirt. The same is true for Charlie in “The Perks of Being a Wallflower,” though his shirt is a raglan tee. Greg Heffley (“Diary of a Wimpy Kid”), Ellie Williams (“The Last of Us” video game), Mike Wheeler, Lucas Sinclair, and Max Mayfield (“Stranger Things”), and both the film and TV versions of Percy Jackson wear the hero’s light blue or navy blue collared uniform. Troy Bolton (“High School Musical”) and Evan Hansen (“Dear Evan Hansen”) wear variations. Though it could be argued that Greg Heffley and Evan Hansen act distinctly unlike heroes, this consistency raises a question: what makes the blue tee work?

This answer is multi-faceted. First, it is entirely unremarkable and wholly functional. The protagonist can be wearing their favorite blue ringer tee when they discover they’re miraculously different and continue to wear the shirt when they take down their mortal nemesis in the franchise’s third movie. Audiences don’t realize the character’s outfit hasn’t changed because they’ve been caught up in the epic highs and lows of the narrative, and they wouldn’t question it because it’s a T-shirt. Unless you’re filming on Hoth, it’s perfectly believable that your protagonist didn’t have the time or need to change clothes.

Second, the color cannot be ignored. The blue isn’t what’s timeless; the gender norms behind it—rather unfortunately—are. Light blue is the color of boyhood, made evident in every gender reveal across the country. And heroism has its roots in boyhood. Save two, every character previously listed is a boy, not a man, unburdened by the struggles of work and structure. They are certainly not girls, who may possess the imagination of heroes but certainly not the freedom of unjudged action and play. The pure heroism of YA media only exists in the imaginative world of a boy, where protagonists inevitably prevail against looming evil threats, which often take the form of adults. Light blue means innocence, but not without overwhelming bravery and hope. It casts these protagonists as boys, indisputably masculine and inherently suited for heroism.

Second, the color cannot be ignored. The blue isn’t what’s timeless; the gender norms behind it—rather unfortunately—are. Light blue is the color of boyhood, made evident in every gender reveal across the country. And heroism has its roots in boyhood. Save two, every character previously listed is a boy, not a man, unburdened by the struggles of work and structure. They are certainly not girls, who may possess the imagination of heroes but certainly not the freedom of unjudged action and play. The pure heroism of YA media only exists in the imaginative world of a boy, where protagonists inevitably prevail against looming evil threats, which often take the form of adults. Light blue means innocence, but not without overwhelming bravery and hope. It casts these protagonists as boys, indisputably masculine and inherently suited for heroism.

Lastly, both the ringer tee and the raglan tee skyrocketed in popularity during the 1960s. The ringer tee became synonymous with youthful rebellion, and protagonists are, above all else, young. Calling upon a nostalgic era of pushing against societal norms—an action that often kicks off YA storylines—allows audiences to empathize with the scrappy protagonist. A well-dressed main character may lower relatability. Any costuming that is too feminine, even for a female protagonist, lowers audiences’ empathy and expectations of the character’s persistence. Placing a hero in an unassuming, vague costume inspired by a now widely accepted period of rebellion pushes viewers to believe in them.

So, time and time again, our heroes don the navy or light blue collared T-shirt. It has become iconic, not because of the strength it bestows upon the protagonist, but because of its utter normalcy. YA heroes don’t have Superman’s crutch, in the shape of a red S and a cape. They have to prove themselves to the audience, which makes their narratives compelling and accessible. We are not all born with superpowers or inhuman intuition. But we can all wear the hero’s blue tee.

Claire Kaltsas is a member of the class of 2027 and can be reached at ckaltsas01@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply