c/o ESN instagram

As alumni, students, and their families strolled along Church Street during Homecoming Weekend on Saturday, Oct. 28, shouts could be heard from a student demonstration outside of Pi Café. A closer look revealed a group of demonstrators calling for the resignation of John B. Frank ’78, the chair of the University board of trustees. Community members have raised his association with the petroleum refinery company Chevron as a potential conflict of interest as the University pursues more sustainability measures.

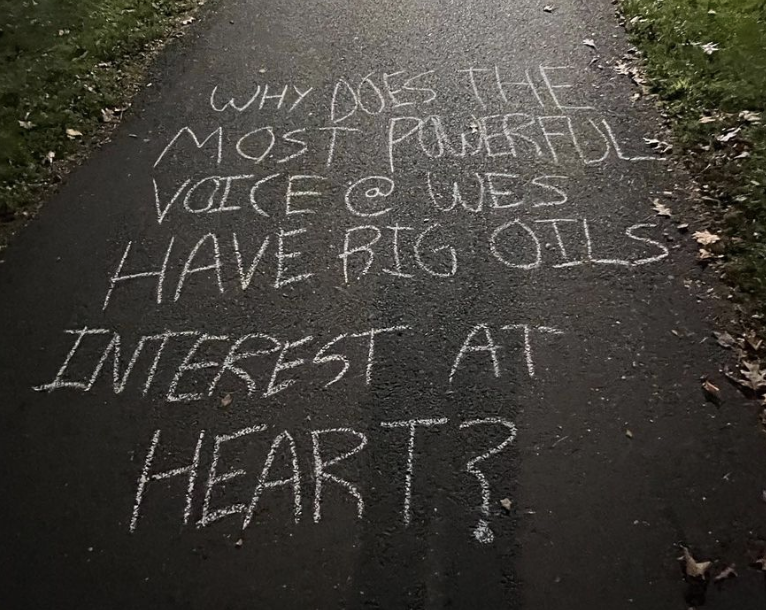

These protests, accompanied by weeks of chalking and meetings, have been part of a larger push to reform sustainable advocacy at the University and mobilize against what many student activists say is an active attempt to use Wesleyan to greenwash the fossil fuel company.

Background

The board of trustees is composed of 37 members. Nine of those members are elected by alumni and serve a three-year term; the rest are elected by the board and serve a 6-year term. Trustees are responsible for establishing long-term policy; presiding over the University’s budget, program initiatives, and construction projects; and supervising the University president. The board meets on campus four times a year in September, November, March, and May for a three-day period and will be meeting this week from Friday, Nov. 17 through Sunday, Nov. 19.

Frank, named chair of the board of trustees at its May 2019 meeting, was appointed for a two-year term beginning July 1, 2020, and re-elected for another two-year term on July 1, 2022. This process adheres to the board’s new tradition of appointing board chair-elects a year in advance to allow for ease of transition.

Frank succeeded previous board of trustees Chair Donna Morea ’76, who was board chair for four years following an eight-year stint as a member. Frank had been on the board for two years prior to his promotion.

“Wesleyan is a special place with enormous impact,” Frank told The Wesleyan University Magazine in 2019. “Every day I rely on the critical thinking and writing skills I developed as a student at Wesleyan. It’s a privilege to succeed Donna as chair, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to work with the board to continue to strengthen this university that we all cherish.”

Frank currently holds a position as vice chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, a global investment management firm specializing in alternative investments. The firm has been criticized for its contributions to the climate crisis, earning a D grade in a Private Equity Stakeholder Project report on environmental sustainability.

Frank’s most controversial association is one with Chevron, the second largest U.S. petroleum refinery. In addition to numerous ongoing litigations, the company has most recently come under fire for a cancer-causing fuel ingredient.

Frank has been on the board of directors at Chevron since 2017. He currently serves as a financial expert on their audit committee, receiving $388,938 in total compensation in addition to the over $4.5 million of Chevron stock that he owns.

“The fact that Frank has been here [since his Chevron appointment] is pretty interesting,” Sustainability Office Coordinator Annie Volker ’24 said. “Especially considering there’s been a whole campaign at Wesleyan about divesting from fossil fuel investment, which has been a big topic for students.”

Wesleyan’s divestment campaign, garnering attention after a 2015 sit-in demanding divestment from coal and private prisons, gained new traction in 2019 with an emphasis on the University’s divestment from fossil fuels. Though the campaign has split over other divestment demands, it has re-emerged in recent months over climate issues.

The Wesleyan Sustainability Strategic Plan (SSP), modified from the 2016 Sustainability Action Plan in part in response to the demands made by the divestment movement, was established in 2022 in order to achieve full carbon neutrality by 2035.

The plan outlines changes in University infrastructure, curriculum, and endowment which will reduce the University’s environmental impact and promote sustainability on campus. The SSP outlines changes in infrastructure, such as replacing the University’s steam system with a newer more efficient hot water system and building new electric car chargers, but some of its most radical plans come in the form of divestment: The SSP outlines “Divesting the Wesleyan Student Assembly endowment from fossil fuels (approving a resolution to divest in 2013, establishing a divestment and reinvestment strategy in 2016, and enacting the strategy in 2019).”

Investigation

The potential conflict of interest was first flagged by Raya Salter ’94, an environmental activist based in New York City. She came upon a report penned by Little Sis—a grassroots watchdog network dedicated to tracking the key relationships between politicians, business leaders, lobbyists, financiers, and their affiliated institutions—and was alarmed when she saw her alma mater in a report about the fossil fuel industry infiltrating executive actions of academic institutions.

She brought this to the attention of the Wesleyan community through a town hall discussion on Oct. 17. This caused uproar amongst student groups, who felt that his position jeopardized the University’s commitment to sustainability.

“Having Frank, who has incredibly close ties and is involved with Chevron, as the president of the board of trustees just shows the ways that Wesleyan loves to talk a big talk, but in action does not reflect it in any way,” Lily Krug ’24 said. “And I don’t think that Wesleyan is the only school doing this.”

Countless other universities are experiencing similar backlash regarding school officials with marked ties to the fossil fuel industry. For example, Harvard Law professor Jody Freedman currently serves on the board of directors for ConocoPhillips and has lobbied the Security Exchange Commission against vital climate regulation, while simultaneously retaining a position as co-chair of Harvard’s Presidential Committee on Sustainability.

Frank is not Chevron’s sole representative in the academic sphere. Members of Chevron’s board of directors have served as presidents, board chairs, and professors at the University of California, Los Angeles; the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; the University of Southern California; and Lehigh University, among other institutions.

Environmental sustainability activists nationwide, and at Wesleyan, have argued that people in similar positions as Frank’s discredit and jeopardize the sustainability initiatives of these academic institutions.

“Now that you’ve seen that John B. Frank, a Chevron director, is heading Wesleyan’s board of trustees, it can’t be unseen,” Salter said. “And so now we are complicit in greenwashing. We’re on the literal Chevron website. And I think it infects everything that we’re trying to do.”

Student Response

The Environmental Solidarity Network (ESN), which emerged from a coalescence of the Wesleyan sustainability and activist community to gather and support broader sustainability initiatives on campus, mobilized their efforts to confront the Frank controversy through peaceful protest. Composed of eco-facilitators, sustainability coordinators, Wesleyan members of the Sunrise Movement, SSP interns, and other student activists, the network’s revival earlier this year has come alongside a wider revival of activism on campus.

As with many other student activist groups on campus, the COVID-19 pandemic diverted attention away from the funding and upkeep of the ESN. The Resource Center did not have the capacity to continue supporting the group, and it subsequently phased out.

In the spring of 2023, members of the Wesleyan Sunrise Movement, the Sustainability Office, the SSP, and other interested parties contributed to the restoration of the organization, aiming to create a space for students advocating for a more sustainable campus and beyond. The ESN is currently registered as an informal student group under the Jewett Center for Community Partnerships.

“I think there’s a real need for organizing around environmental issues on campus and creating just a platform for students to connect with each other,” ESN Administrator Volker said. “Our goal is not to necessarily only do all these optimistic things, but also to help people do projects related to sustainability on campus, and tackle its issues.”

Salter’s call to action coincided with the ESN’s re-establishment earlier this year. Though the group has numerous other ongoing projects, ESN members felt that speaking out on Frank’s appointment was a student obligation, and they have prioritized spreading word of the ongoing controversy via petitions, rallies, and town halls. The board of trustees could not be reached throughout the process.

“There is an absolute maze of red tape around meeting with the board,” Co-Coordinator of ESN Isaac Ostrow ’26 said. “Which again, is absolutely disheartening, because that is one other obstacle.”

A QR code is currently circulating around campus, linked to a Google Form petition entitled “Say No to Fossil Fuel Control at Wes!” Within the form is an open letter written by Salter and Amy Tai ’88 to the board of trustees and President Michael Roth ’78. The letter states that Frank’s appointment is a form of de facto greenwashing and is directly in conflict with the University’s sustainability initiatives. Calling for Frank to step down is the first of many actions the University can take to establish a board that students can trust, according to Saltar and Tai. The ESN petition had 400 signatures as of Thursday, Nov. 16, with 80% of those from students.

“Wesleyan, its students, and its alumni community have a duty to protect the planet,” the letter states. “So why do we allow a representative of the Chevron Corporation, the third largest multinational fossil fuel operation by market cap, to head our Board of Trustees?”

Last school year, a petition to cover all abortion-related costs for University students, titled “Reproductive Rights at Wesleyan Now!” garnered over 740 signatures, and was subsequently honored by the University. The ESN hopes to achieve a similar number of signatures for this petition, as well as broaden general engagement with the Frank issue.

In addition to sharing the petition, ESN members also placed informational flyers around campus. They noted that these flyers seemed to be singled out: All ESN-related flyers were removed while other flyers stayed up.

“I don’t want to attribute any blame,” Volker said. “But in bathroom stalls we’ll put up things, and then the one poster there for Vish will stay up and then our poster will go down…. The University must be issuing some sort of orders or some students are trying to limit the spread of this information, which is just pretty funny…. All this information is available online. Just search up John B. Frank.”

Although Roth acknowledged that the University’s policy is to remove posters from certain locations, he denied that the University was targeting the ESN.

In addition to all the flyers and social media posts, the ESN hoped to take the University’s annual Homecoming and Family Weekend as an opportunity to inform interested parties who aren’t normally on campus to see the posters—namely, alumni and parents. The organized rally coincided, purposefully, with the reveal of the University’s $600 million fundraising campaign.

“The goal was to get the attention of parents, alumni, students, all of whom are very rarely on campus,” Ostrow said. “And so we staged that event there in order to get the issue of Wesleyan’s specific ties to fossil fuel out into the spotlight.”

The rally was also intentionally slated to occur after the College of the Environment’s Annual Symposium in Exley. As guests exited the building at noon, moving toward the football game on Andrus Field, their heads turned toward yet another demonstration of student life at the University: peaceful protest.

“We intentionally planned to have it during Homecoming, where there’s typically this huge showcase of what Wesleyan is,” Volker said. “We thought no better time to say what Wesleyan is than what they don’t want you to know…. [They] present us as such a forward-thinking, progressive institution but do all these things.”

Public Safety (PSafe) officers had an unusually large presence near the rally and within Exley, radioed in within minutes of the rally’s start. One student reported having their ID taken and said they were issued multiple points for participating in the demonstration. Most notably, PSafe officers were seen intentionally redirecting alumni and families through Exley’s back entrance facing Lawn Avenue, away from the protest, the Andrus Field football game, and the majority of other Homecoming events. Directly after the College of the Environment Symposium in Tischler Hall, the back doors were propped open and officers guided guests out of earshot of the rally.

“I mean, we expected resistance,” Volker said. “And clearly, this isn’t what Wesleyan wanted to convey. But it is pretty interesting that Michael Roth released his books about students and their free thought…and he’s making people direct away from student activism.”

The ESN took special precautions prior and during the rally. Members chalked beforehand, made their intentions clear on posters and social posts, and did not block main entrances. Nevertheless, PSafe monitored and stifled rally speakers, according to attendees.

“PSafe has given out points to people who chalk on Wesleyan property if they’re caught,” Ostrow said. “They are very active in getting their pressure washers out and getting rid of chalk, expediently.”

Roth commented that it is not the University’s policy to disperse protests.

About a week before the Homecoming rally was scheduled, Salter arrived on campus to discuss the importance of the fossil fuel industry’s influence on college campuses with the Wesleyan Democrats (WesDems) group. She referenced pro-fracking studies conducted by Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Ernest Moniz as a prime example, almost entirely funded by oil stakeholders. Moniz later served as the new secretary of the Department of Energy.

“Mr. Frank’s position at Chevron and his mass ownership of stock gives him a direct incentive to gut sustainability efforts,” WesDems Student Community Director Sophie Fetter ’25 wrote in an email to The Argus. “How has he influenced the allocation of the endowment? Can divestment truly happen by 2035 with him on the board?”

Lily Krug ’24 offered a more optimistic view of Wesleyan’s ongoing sustainability efforts.

“I want [protests] to continue until [Frank] steps down,” Krug said. “And I want that to spark a resurgence of environmental activism on campus.”

Frank’s term as chair-elect of the board of trustees will end in May 2024. Roth confirmed that Frank will be stepping down from a trustee position, although he declined to comment on the controversy. The ESN’s primary goal is not to demand personal divestment from Frank but to bring attention to the University’s complicit role in greenwashing.

“We want to let the board know that the students are watching,” Ostrow said. “We see through their red tape and their deliberate opacity…their refusal to meet with us, and their refusal to make their minutes visible. We see through that, and we understand that the board, as it is now [stands] has a long lasting conflict of interest that will continue to impact [Wesleyan] policies…over the coming decades.”

Carolyn Neugarten can be reached at cneugarten@wesleyan.edu.

Miles Craven can be reached at mcraven@wesleyan.edu.

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify trustee appointments. Donna Morea served as chair for four years and board member for twelve.

3 Comments

alasti

Prof. Jody Freeman in fact resigned from her position on the ConocoPhilips board of trustees, after much protestation by Harvard affiliates concerning that egregious conflict of interest.

DKE Bro

Oil bad

Diversity good

Hoo hoo ha ha

John Bissner

I am deeply disappointed by this article, which questions the great oil and gas industries that are the basis of American power and life. Carolyn and Miles, please learn a little bit more about how the country works as you continue your studies at Wesleyan. Your specific breed of extreme leftism counters the neoliberal system that has lead America to success at home and abroad.