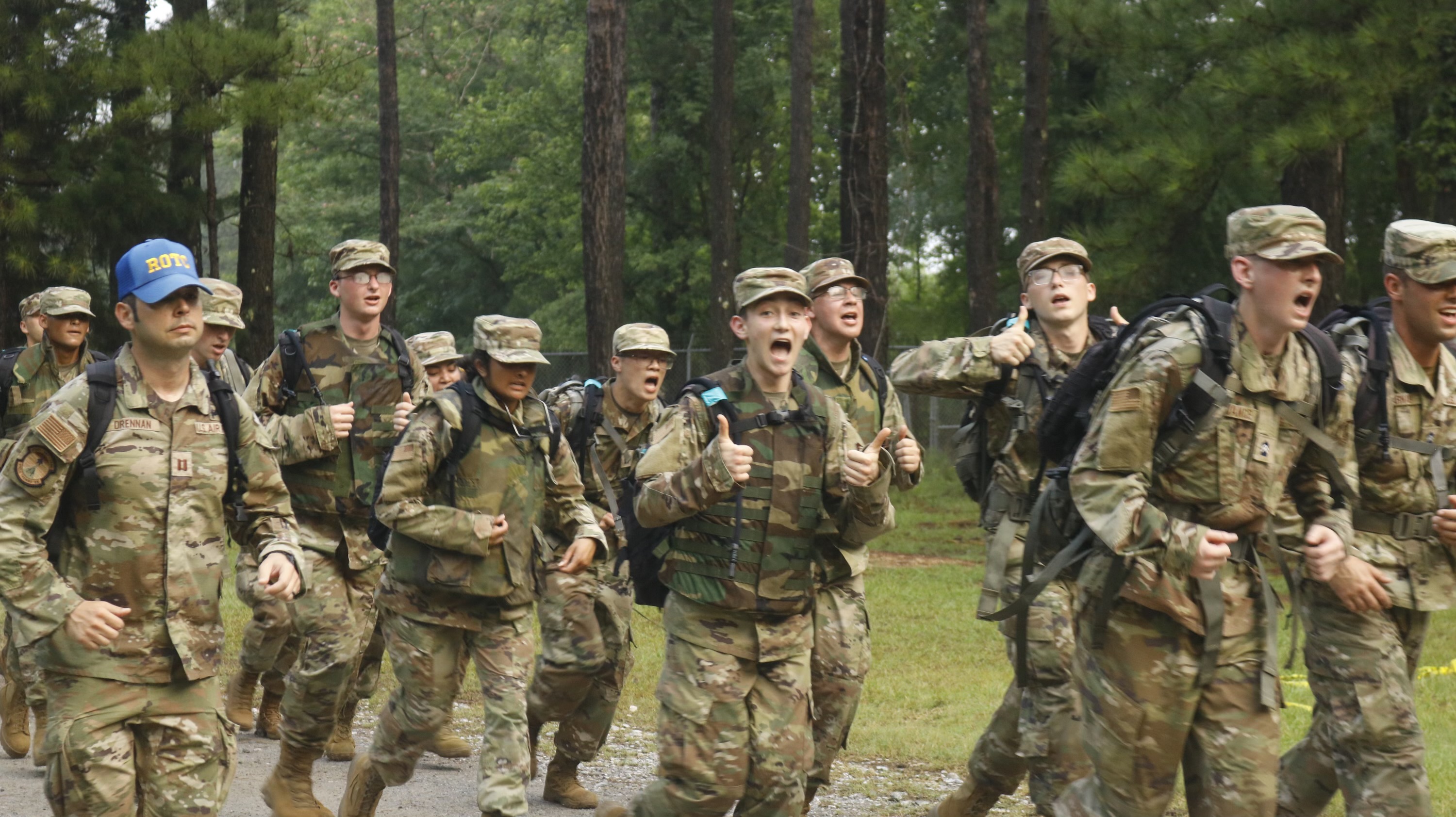

c/o Thomas Lyons

Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps Program (AFROTC) at the University Today

On Tuesday and Thursday mornings, Nate Zola ’25 wakes up at 4 a.m., shaves, eats breakfast, and commutes to New Haven for physical training. Zola is currently the only active member of Wesleyan’s Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps program (ROTC), which operates through Yale University’s Connecticut hub.

While Zola initially wanted to attend the Air Force Academy, he applied to Wesleyan knowing he could either participate in the partnership Yale Air Force ROTC program or decline Wesleyan’s offer if he was admitted to the AFA.

“I always knew I wanted to be in the military,” Zola said.

The Yale program, which consists of students from Wesleyan University, the University of New Haven, Western Connecticut State, Southern Connecticut State, Quinnipiac University, and Sacred Heart University, grew from 58 to 78 cadets this year according to Zola. He attributes this increase to better public marketing.

While the military offers some cadets scholarships during their first year of college, Zola did not initially receive a scholarship and felt he needed to work twice as hard to prove himself to the others. Despite this competitiveness, Zola stressed that ROTC is different from the movies.

“It’s much different than people imagine,” he said. “You’re not immediately in uniform getting yelled at.”

Still, cadets entering into the AFROTC are not guaranteed spots at field training in Montgomery, Ala., during the summer of their sophomore year. The required summer training teaches cadets hands-on leadership and tactical skills and accustoms them to life in the military. Enrollment in the program is dictated by fitness test results, a cadet’s GPA, and their commander’s ranking score (the flight of cadets is ranked into thirds). Space at summer training is so limited because the AFA generates roughly 1,000 officers per class year, which leaves 2,000 to 3,000 AFROTC officer candidates to compete for the remaining spots. Those not offered a slot often cannot continue with the ROTC program and must pay back any scholarship funds, according to Zola.

“There is competition with peers, as you’re competing with them for commander’s ranking,” Zola said. “But everyone feels bad if someone doesn’t get a spot at summer training.”

According to Zola, there are currently 20 total sophomores in the Yale AFROTC program. Zola estimated that roughly 14 will go to summer training.

Life at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama is the extreme extension of daily training with Yale’s ROTC program. However, the tough conditions are intentional.

“You’re marching everywhere except during Black Flag weather [when temperatures climb over 100 degrees],” Zola said. “[By the end of the 16-day program], you become a better officer candidate, a better follower.”

This emphasis on becoming a good follower is central to the ROTC education. Thursday afternoons, Zola and fellow cadets attend Leadership Lab, where, as first-years, they learned marching patterns and what are termed the “the fundamentals of followership.”

“[Sophomore year], people who return [to the program] are met with a whole new level of intensity,” Zola said. “That’s when you learn to become a leader.”

Sophomores also receive their uniforms, which is a rite of passage for those in the program. Cadets are required to wear their uniform every Thursday from the time they wake up until they attend Leadership Lab at Yale later in the afternoon. Zola acknowledges he sometimes gets strange looks when wearing his uniform around campus. Despite straddling the line between two very distinct worlds, Zola feels comfortable with his involvement in both environments.

“The program creates a good environment for any Wesleyan student,” Zola said. “You don’t have to be 100 percent gung-ho about the military to try it out for the first year.”

That said, the ROTC program has impacted Zola’s college experience. He now receives a scholarship from the program and has access to opportunities such as internships at the Pentagon. Unlike the stereotypical college student, he goes to bed as early as 7:30 p.m. some nights. Like any cadet, Zola is also forbidden to consume any illegal substances and must report all civil involvements (speeding tickets, for example) to the military within 72 hours.

“When you’re done with the four years, you’re not finished being evaluated, ever,” Zola said.

Looking ahead, Zola hopes to become a combat systems operator, although he originally wanted to be a pilot. Both positions are rated, meaning Zola would have to serve a minimum of eight years in the Air Force.

Wesleyan’s Relationship to the Military

Military service has not played a large role in the University students’ undergraduate experience for the past few decades. On the front page of The Argus’ April 20, 2004 issue, a blurb in the bottom left corner reads, “Wanna join the army? No really. We’re not kidding.” The blurb leads to an interview by then-Metro News Editor Katharine Hall with Armed Forces Career Center recruiter Sergeant Edward Ford.

“We are looking for committed Americans,” Ford said in the article. “Someone who has personal courage, respect for themselves and for others…. I do know that there are other colleges who have people that are more interested in serving than they are at Wesleyan. Is it because [Wesleyan] students don’t know about the programs, or is it something else?”

Kelleigh Entrekin ’25, who also participated in Wesleyan’s ROTC program before leaving after her first year, argued that today it’s a mix of the two. As a high schooler in Mobile, Ala., she felt encouraged to participate in Junior ROTC.

“There were constantly military recruiters around,” Entrekin said.

Since Entrekin was always around recruiters, she knew joining the military was an option. Entrekin thinks that this difference in exposure to people in the military is one of the main reasons why so few Wesleyan students are involved in ROTC.

“I don’t think [ROTC programs are] on anyone’s mind,” Entrekin said.

While the ROTC program provides military training during the school year for many college students, students at the University have taken other opportunities to pursue similar training pathways. For example, Audrey Maxim-Rumley ’25 attended the Marine Corps Officer Candidates School in Quantico, Va., this past summer.

“I always had a fascination with the military, but my family growing up had no connection to the military,” Maxim-Rumley said. “That felt odd to me…. I didn’t know what I wanted to do [for the summer], but I knew I wanted to be involved in service. I wanted to do something hard and build up grit. I wanted to meet people who thought and grew up differently than me.”

These desires led her to enroll in the Marine Corps Officer Candidates School program, an experience she knew little about.

“I didn’t do a lot of research on purpose, so I didn’t have a great idea of what I’d be doing,” Maxim-Rumley said. “I didn’t think I’d have any trouble completing the six weeks…. It was the most difficult experience of my life. I got inflamed cartilage in my ribs. I got viral pneumonia. I slept two to three hours a night on average. We ran on gatorade, and water, and really good biscuits.”

Despite the harsh conditions, Maxim-Rumley persevered.

“There’s no way to describe it that sounds appealing, but something in that environment was exhilarating,” Maxim-Rumley said. “I still consider going back.”

The Marine Corps officer training program consists of two six-week sessions over consecutive summers, according to the school’s website. Cadets must complete the second summer’s training to graduate into the Marine Corps.

Maxim-Rumley’s attitude toward the armed forces wasn’t completely positive.

“I do have misgivings about the U.S. military,” Maxim-Rumley said. “I wasn’t morally totally invested in the Marine Corps. To know you’re part of the most elite war-fighting force in the world—sometimes that feels like a disgrace and sometimes that feels like an honor.”

Despite her qualms, the unique community of women helped Maxim-Rumley push through the program, which ended with about half of the 42 officer candidates still enrolled.

“Someone is supporting you, and you are supporting them,” Maxim-Rumley said. “When you’re not failing, it feels amazing.”

About a quarter of the cadets were attending military schools according to Maxim-Rumley, and all had or were in the process of getting a bachelor’s degree.

Due to the intensity of the program, Maxim-Rumley formed close bonds with many students with whom she had little in common, relationships she doubts could have existed outside of the military setting.

“There were people there who if we knew more about each other, there would be no way we could be friends,” Maxim-Rumley said.

Although the program was a catalyst for close bonding, she found herself questioning the program’s extremity in the weeks after the session ended.

“Often I struggled with the question of ‘Is what they’re doing necessary to create the leaders they want?’” Maxim-Rumley said. “No, I don’t believe that.”

Even with this imbalance, Maxim-Rumley cautiously recommended that, for some, service could provide an opportunity to create meaningful change.

“If you think you’re not finding how you want to serve the world, I highly recommend the military,” Maxim-Rumley said. “You have to have some grit.”

Thomas Lyons can be reached at trlyons@wesleyan.edu.

4 Comments

DKE Bro

Good article. With the drug use that abounds and the better tools the military has to screen out candidates based on medical history, I doubt many Wesleyan students would be qualified to serve even if they wanted to

WesStudent

I’m curious as to why you wrote an article about military training and service at the school and chose not to mention or talk to the almost twenty veterans that are enrolled?

Thomas Lyons

Totally fair question! The article aimed to explore the perspectives of Wesleyan students in undergraduate training programs who were preparing for future involvement in the military, specifically the ROTC program. To my knowledge, the current veteran students at Wesleyan would not have trained through these specific programs and so felt outside the scope of the article. My original article title better reflected that scope, but was later changed in an editing stage in which I was not involved. Ultimately though, you’re right to point out the piece lacks that important perspective, and I encourage you to report on those perspectives.

VeteranStudentAlum

Additionally, there are more student veteran alumni in the last 5 years at Wesleyan than in the 25 years prior to that. Go ask the library to review the documents relative to Wesleyan’s time as a military training institution throughout its history.

The fact that you interviewed a prospective member of the military and a person who quit ROTC after 1 year and none of the dozens of veterans recently associated with the university is disingenuous. Students actively burned the flag in front of disabled vets on Veterans Day during my time as an undergrad in the last decade.

If you want to talk about the history of the military community at Wesleyan, a good first step is to learn the history. If you weren’t involved in the retitling, then I would kindly ask that you share with your editors their woeful incompetence to report on the topic.