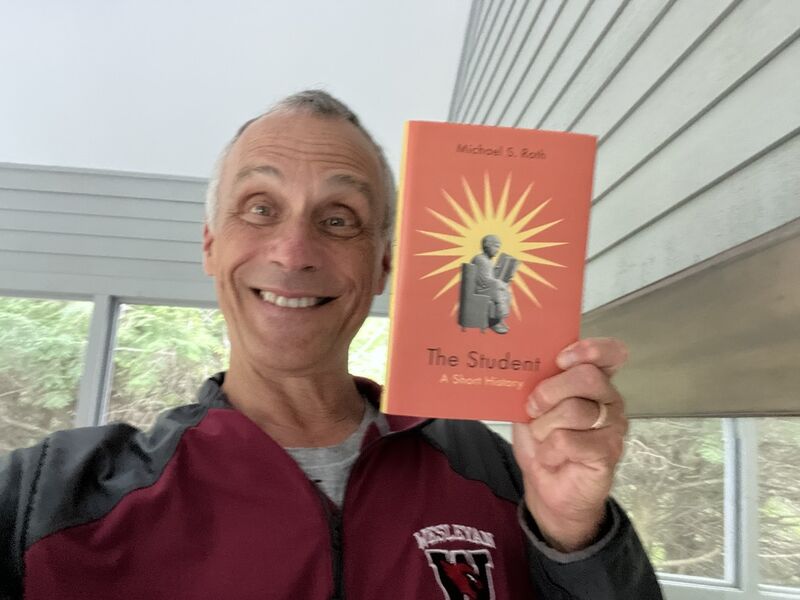

c/o Michael Roth

In his “Meditations,” Emperor Marcus Aurelius thanks his grandfather for keeping him out of school, describing it as one of the most significant gifts of his life. Although Marcus was an avid pupil of Stoic philosophy, most Romans of his class endured a curriculum of rote memorization that left them incurious and averse to education. In the 21st century, though, school has expanded beyond a vehicle for toga parties, and student-hood has become a near-universal stage of adolescence. In “The Student,” published on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2023, President Michael Roth ’78 tracks the different modes of learning that constitute the modern student and celebrates the perpetual learner, defined as one who continues to pursue enlightenment and then emerges from their self-incurred immaturity. At only 200 pages, “The Student” is far from a comprehensive history. Rather, it surveys a variety of practices, teasing out the ways students have developed independence.

Roth begins by examining the students of three historical teachers and the examples they set for the modern pupil. Confucius’ followers cultivated virtue to promote harmony in turbulent times. Socrates’ interlocutors discovered their ignorance and dispelled sophism through ironic critique. Jesus’ disciples achieved rebirth through pious reception of their teacher’s truths. For Roth, each of these modes is essential for the student, though none should be adopted to the exclusion of the others. For example, Roth rejects Socrates’ bottomless irony in favor of “critical feeling,” the empathy to understand why an unsympathetic idea would resonate in its own time and context.

Skipping to premodern Europe, Roth explores how apprenticeships developed youth independence. With literacy scarce and books inaccessible to all but the privileged and the clergy, these vocational relationships were the most common form of study. Students would provide labor for their masters in exchange for access to a trade, but they would also receive a moral education and follow behavioral prohibitions against indecency and romance. Autonomy from their parents, paired with new skills and norms, would allow them to exist independently within their communities. Roth highlights how Benjamin Franklin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau each carried the discursive habits they absorbed in their trades into their writings on independence and freedom.

However, autonomy was not sufficient for truly free thought. As Roth notes, Immanuel Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” saluted the independent learners who, in the spirit of the age, dared to stand on their own reason. Decades earlier, the philosopher John Locke and historian Charles Rollin had each emphasized education as a means of developing moral fortitude, and at the same time, Denis Diderot’s “Encyclopédie” brought scientific knowledge to the public at scale. In Kant’s time, though, education remained mired in tradition, and universities mostly emphasized memorization over knowledge creation. This began to change in part due to Rousseau’s treatise “Emile,” which promoted an education that allowed students to cultivate their passions and capacities. In Prussia, the university was reoriented to weave teaching and research together under the protection of novel academic freedom. As the aims of education shifted, so too did the student. Through Bildung, which is the process of self-cultivation, they would determine their own paths and freedoms.

Liberalized curriculums did not entail inclusivity, though. The early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft criticized Rousseau’s dismissal of women in “Emile.” In “Vindications of the Rights of Women,” she argued the importance of women’s education for societal well-being. Roth traces how W. E. B. du Bois made a similar argument for Black students throughout and beyond his education, from Fisk University to Harvard University and Humboldt University. Both used the language of freedom to demand space as students, though their demands were not fully met in either’s lifetime.

Roth acknowledges that students cannot be reduced to their struggles for truth and liberty. Along with the development of the student came the development of student culture, from dueling in 19th century Prussia to hazing in the contemporary United States. Student mischief is nothing new; Roth dates the tradition of abusing first-years to as early as the 1400s at Oxford and Bologna. However, in Roth’s telling, fraternities became the primary means of protecting college men and their habits in the 19th century. Fraternities and, as women enrolled in the early 20th century, sororities, served to preserve societal hierarchies while education provided a chance at social mobility for poorer students. Many Greek organizations excluded Jewish people, Black people, and Catholics while promising post-graduate connections for their devotees. However, Roth claims that the influx of veterans after WWII helped quash these discriminatory practices, as older men—being skeptical of masculinity in fraternities and having opposed injustice abroad—mixed with their peers. The university and its institutions were no longer places meant to encourage one way of thinking; now they were targets for independent student thought.

As the Vietnam War and social upheavals of the 1960s roiled campuses, students, especially groups like the national left-wing activist organization Students for a Democratic Society, began to demand more expansive freedoms from the university. Roth describes how they attacked unjust hierarchies, organized against segregation and the war, and forced universities to reform their curriculums and admissions systems. As the Summer of Love in 1967 rolled into several winters of discontent, a few of these students turned to domestic terrorism, but most left radicalism behind and joined the ranks of the swelling professional class. Though the youth culture of the ’60s was quashed by the realities of the ’70s, the university as a venue for further expanding freedom was cemented.

Until it arrives at the present day, “The Student” is a lucid account of the development of its subject. The book reads quickly and, though Roth mostly limits himself to Western European ideas about learning, illuminates the development of freedom through study as a broad concept. However, Roth’s suggestions to promote freedom in today’s education won’t shock readers familiar with the genre.

Roth thinks that college should be more accessible to people from all classes, that intellectual conformity is unhealthy, and that economic inequality is bad. He disparages how colleges have become meritocratic proving grounds, where learners compete for dream jobs in mergers and acquisitions; he laments how middle- and upper-class parents hoard opportunities to ensure that their children, no matter their capabilities, are selected as those chosen few. The extent to which his actions as University president reflect these concerns is left as an exercise for the reader.

It’s uncharitable to fault “The Student” for its exclusions, given its scope and length. Nevertheless, a few absences stuck out. The Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire, whose 1970 “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” was foundational to the field of critical pedagogy, is given only a glancing mention. Freire’s friend and interlocutor, Ivan Illich, is excluded entirely, despite the importance of his work to both New Left radicals and Governor Jerry Brown. Illich’s “Deschooling Society,” although obviously flawed, provides a truly comprehensive framework of the perpetual student that might have given Roth’s book more weight when addressing the future. “The Student” is a historical, not theoretical, work, but the book’s ending comments about minor reforms leave the reader wondering if freedom really is best pursued through tweaks to college admissions and project-based learning.

For students (perennial or otherwise) interested in completing enlightenment, it might be more fruitful to return to Kant. For those interested in a bright history of the process, “The Student” is available at Olin, at various bookstores, and online.

Correction: The article originally stated that the Summer of Love was in 1969. However, the Summer of Love was in 1967. This has been updated.

Reed Schwartz can be reached at reschwartz@wesleyan.edu.