c/o J.W. Hendricks

Intern season is over. There will be no more polo shirts lined up in front of the hippest bar every weekday after 5 p.m., no more LinkedIn posts about amazing, meaningful experiences, and certainly no more “circling back,” “checking in,” or “touching base.” But the intern experience is also not what it used to be. In the current post-pandemic trend towards complete digitization, it seems like nearly everything has gone online, especially when it comes to the workplace—or more accurately, the work-from-home-place. This has also led to the introduction of the remote internship, which, at this rate, will be ultimately harmful to the future careers of nearly everyone my age.

At first glance, the working-from-home movement seemed to be the perfect answer to the horrible work-life balance (or imbalance) proliferated by American culture. After all, it’s arguably the biggest change to employment as we know it in the past century. With communication being done over Zoom or via email, people have more freedom to make their own schedules, maintain their mental health, and spend time with their families. Without having to commute every day, parents can more easily care for their children. A recent survey found that over 40% of U.S. employees would start looking for another job if they were asked to return to a completely in-person schedule. Another report found that 76% of employees want flexibility regarding where they work, and 93% want flexibility regarding when they work.

I get it. Remote work is not going away anytime soon, and it does sometimes seem like the only people pushing to get back to the office are the evil employers who only care about profit and productivity. However, there are reasons that remote jobs are especially detrimental for college-aged young adults. If you are over 35 and have been at the same company for a number of years, it makes sense that you would not want to go in to work. You’ve already done your time and have established relationships and routines. And you most likely have a family or circle of friends you would prefer to spend time with.

Now consider the average 22-year-old: fresh out of college, ready to work and start a career. At this point, we (including myself) are all at various transition points, trying to put down roots and settle down in some way. The absence of an in-person work environment definitely hinders this process. I have been fortunate enough to have both remote and in-person internships and can confidently say it’s a more worthwhile experience when you actually get to meet the people and talk to them in real life. Only being able to see a small face on your computer screen is not an ideal way to build a relationship. Furthermore, you’re way more cut off from other interns, meaning you’re not socializing with other people at similar stages of life.

But the remote internship is only part of the problem. In some ways, it feels like the class of 2024 will be entering an insanely uncertain job market. This is not because there is a lack of jobs available, but because of the changes that have come about post-pandemic—specifically, the wider national and international labor movements.

Last semester, I studied abroad in Paris during a period of what was described to me by Parisians as “once-in-a-lifetime” strikes. The workers of the Régie autonome des transports parisiens (RATP), France’s public transportation operations system, led a series of strikes, riots, and demonstrations that stopped the flow of traffic in the city for days at a time. At the height of these strikes, it was impossible to board the metro without narrowly avoiding a crowd crush. Inspired by these strikes, sanitation workers stopped collecting trash in the city to protest in favor of their own demands. Because strikes are generally more common and accepted in France than in the United States, the global sentiment seemed at first to be one of slight ridicule. “Oh, those crazy French with their healthy work-life balance, they’re back at it again!” However, these movements now seem representative of a larger movement that arrived shortly after.

This past summer was deemed “Hot Strike Summer” by the American media, as flight attendants, Starbucks baristas, and UPS workers, among other groups, all either organized strikes or used the threat of a strike to attain better and safer working conditions; other unions, like the United Auto Workers, plan on striking in the coming days. The University also recently experienced its own labor organizing movement on campus last semester, with the establishment of Dining Workers United.

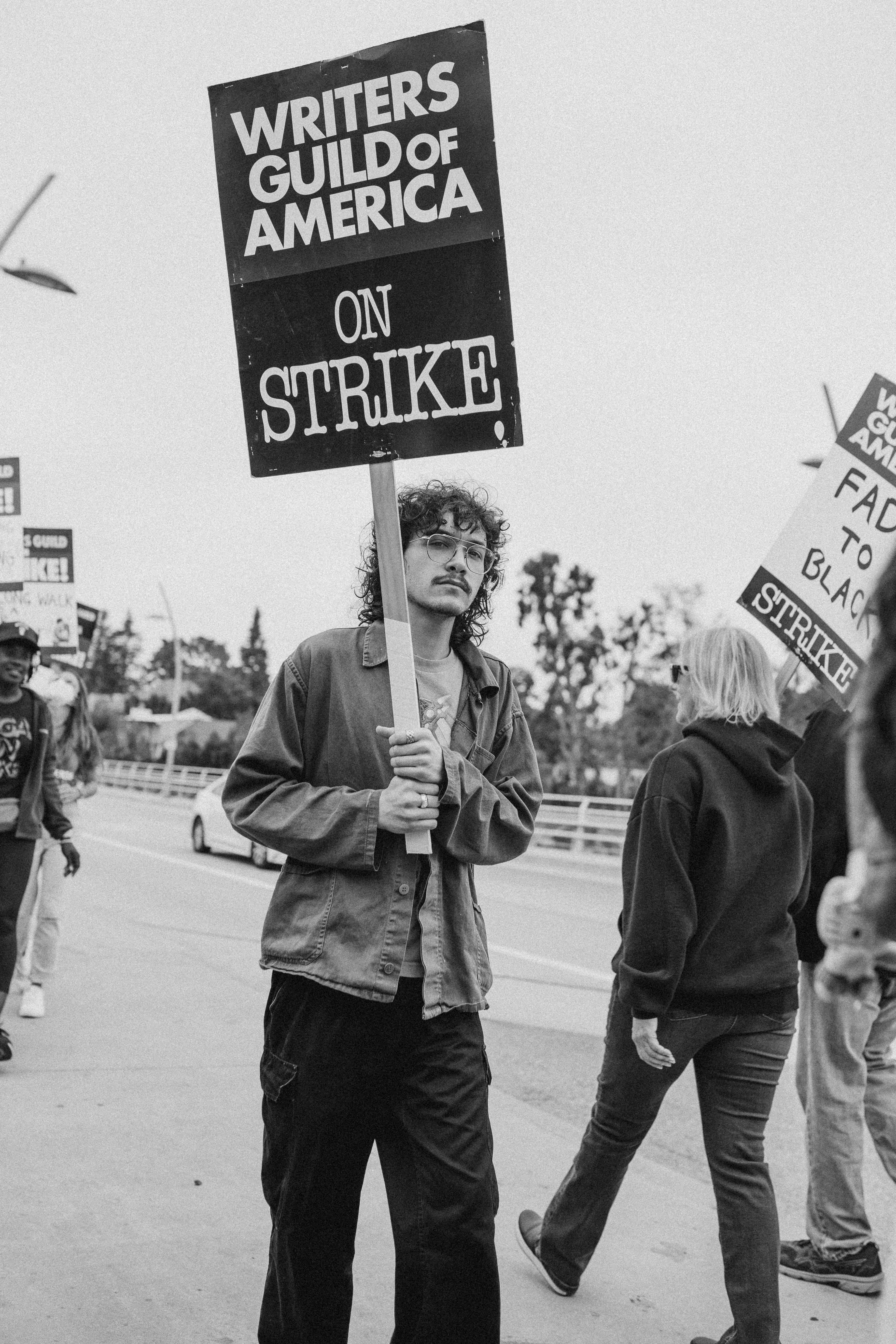

In my personal life, my dad and brother are both on strike as members of The Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild respectively, and have been on the picket line in Los Angeles for the last few months. Therefore, I’ve been thinking and talking a lot about what this all will mean for us young people in the coming years. In the case of the entertainment industry, getting a job and working in production will never be the same. The way we consume content is ever-changing, and the growing amount of high-turnover, short-term projects, coupled with society’s short attention span, spell an ultra-competitive field, not to mention the looming destructive potential of artificial intelligence. For people my age, it is an extremely turbulent time to be launching a career in film and television.

The point of this article is not to argue that unions are going to soon become more popular than ever before. Despite a union membership surge amid record-low unemployment rates, the percentage of union membership nationwide has actually been in decline for decades. Instead, what stands out to me about “hot strike summer” has to do with why I started talking about remote internships in the first place. The world is changing the way we interact with work, and while this might ultimately be beneficial in the long run, for now it means that it’s up to our generation to set boundaries and implement the systems that we want. This is a tricky position: the more inexperienced an employee, the less negotiating power they have. So what do we do about it?

There is good news and bad news. The bad news is that we will be the demographic most affected by the current changes taking place. The good news is that the recent spread of on-campus labor mobilizations means that we are already recognizing that these changes are going on and are willing to put in the work needed to improve our situation. But to me, the most important thing is that we remain aware of what is happening. It is not normal to try and get to know a mentor simply through Zoom group meetings once a week. It is also not normal to have a bunch of empty office buildings sitting around that remain the property of companies, but never get used. And it is certainly not normal that the whole country is owned by three gigantic corporations, and that the rest of the world will soon be taken over by Amazon.

The American labor market is in a state of transition. My generation has long been characterized (sometimes unfairly) for being lazy, selfish, and wanting to obtain whatever we desire without having to put in the work to get it. And there is some truth in this: after all, we are often primarily concerned with our short-term circumstances. But this issue has greater implications for our future careers and future communities. We have to appreciate the value of our labor and how it fits into the greater, evolving puzzle that is society.

Emma Kendall is a member of the class of 2024 can be reached at erkendall@wesleyan.edu.