Since March 28, The Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery has featured this year’s Art Studio Senior Thesis Exhibitions. The fifth and final week of solo exhibitions took place from Tuesday, April 25 through Sunday, April 30, featuring the work of Michael Eustace ’23, Stella Guggenheim ’23, Harrison Haft ’23, Julia Kaubisch ’23, Leah Levine ’23, Nélida Samara Zepeda Mendoza ’23, and Savannah Russo ’23. The gallery showcased a variety of enchanting uses of space and objects, each striking on their own and yet tying the space together.

Upon entering Zilkha, I immediately turned right into a room featuring Zepeda’s installation, “Ezkotin Tlalli,” where photographs lined three of the walls, and five leaves hung on the fourth. Inspired by her dual passions in art and the environment, this series of photographs evoked an emotive sense of natural beauty through the interplay of the landscape’s interaction with natural light or the rawness and contrast of the human form. In one, the waves of the water glimmer across the wake, framed by an outcrop of branches along one corner of the frame. Another features the back of a person, crouched with their spine protruding outwards of the skin against a backdrop of darkness. While some provided a clearer, sharper subject, other images were more abstract.

“Photography, for me, is a powerful tool for reflecting and processing” said Zepeda. “I think the photographs themselves…reflect that aspect of my artistry…. The photo making process, because I shoot in film, is very much a slow [intentional] image making process that reflects the feeling or the emotion of the land or the place or the person that I’m with. So I think overall, it’s about the emotion of that moment.”

Another photograph in the series, titled “Water Women,” was particularly visually striking.

“I took this photo [when I] went on this beautiful hike and it was very spiritual and we’re connected with the land and singing songs and connecting with the water” Zepeda said. “And my friend, she’s a beautiful singer and she was singing these water songs, she calls them moment songs and it was just in the moment whatever was happening or coming through her, and I saw…my favorite little waterfall at this place we went to. I just love sitting back there, behind the water. It’s like really tight. Basically, you can sit like this, behind the waterfall that falls over your head and there’s a rock right here. And it’s so beautiful. I had her sit inside and she was singing these songs. And I took a picture. And it looks almost like, my professor was like, ‘Is this a double exposure?’ Because it just doesn’t even seem real. I think that’s one of my favorites, but I just love the ones that are kind of like hyperrealistic or kind of fantastical. Like, is this real?”

In crafting this series, Zepeda took interest in the process itself, seeking the depth provided by the darkroom without the harshness of the chemicals. In searching for an alternative printing system with a similar quality, Zepeda found an analog: making their own recycled paper.

“I had to start developing alternative ways of printing that would also give the same kind of feeling that darkroom photography does,” Zepeda said. “I feel like there’s just more depth to the image as opposed to a digital print. I don’t know, having looked at so many images, I feel like I can just feel the difference. But anyway, I wanted to kind of keep that like depth through a different process. And so I was like, what if I make my own paper? And somehow I successfully managed to make paper that can go through the printer. And the way that the ink goes into the paper was something I was not expecting because it has darker blacks and it’s more saturated…it’s very immersive in that way.”

Moving into the next section of the gallery, the entryway presented Haft’s “Acmesthesia.” In this area, I was particularly taken by two paintings along the wall: One which featured a portrait of face, with the face’s interior continuing within itself—an effect like seeing a mirror through another mirror—until a small complete image of the face resides in the middle. The other painting took on a different color tone, darker and less bright, the grid of bars in the foreground and person in behind them provide a sense of entrapment and imprisonment. This essence is further felt through the surrounding colors and streaks of red, mixing a rawness into the piece.

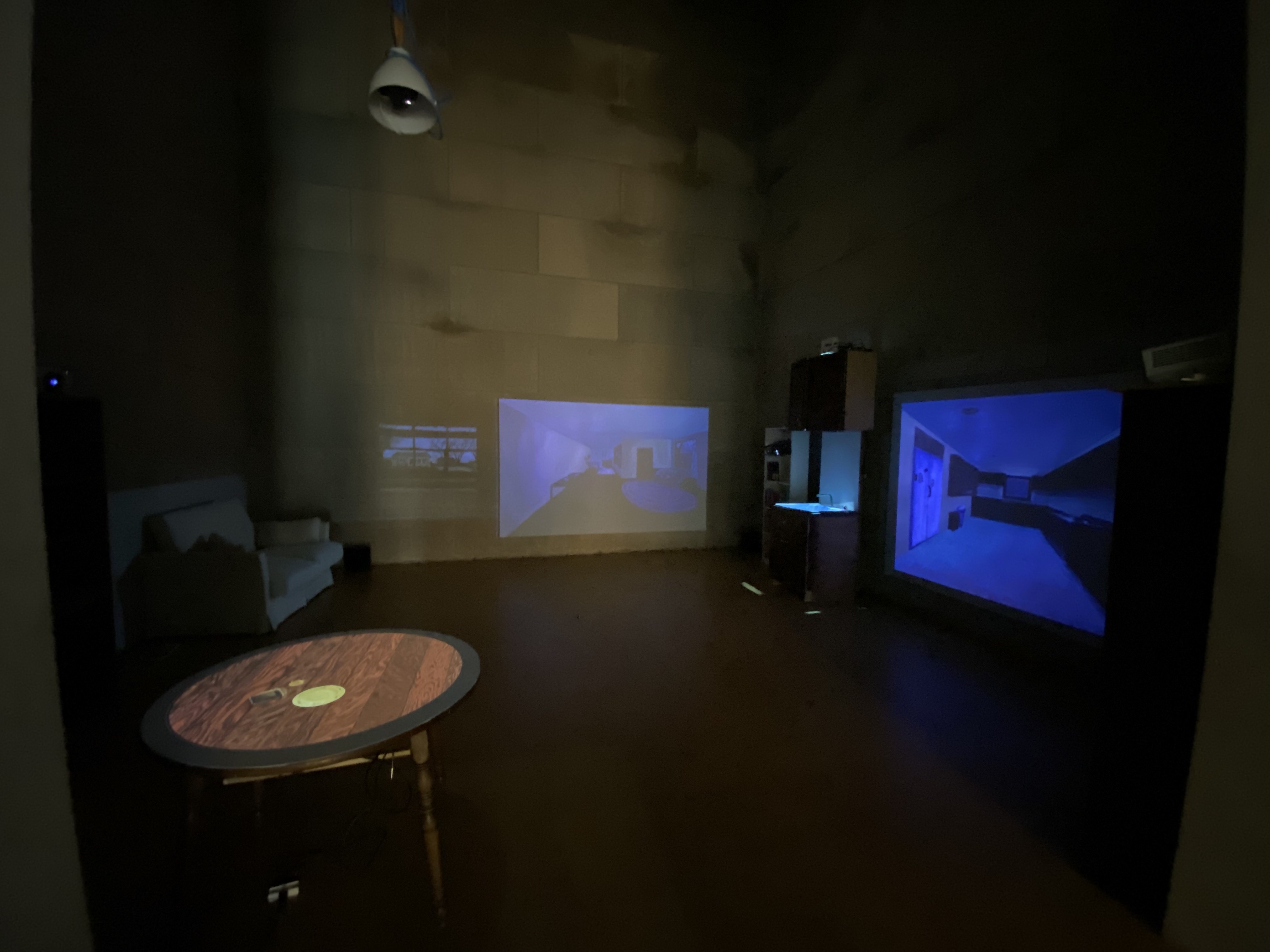

Continuing forward, the brightness from the windows gracing Zilkha’s halls darken on approach to the outcrop featuring Guggenheim’s “Dwelling.” The space took the form of a living area, a couch in one corner, a table on one end, and a sink and cabinet in another. Against the walls were projected videos, allowing one to see through a window as well as extending the room itself to see other adjacent areas of the house. Another two projectors resided above the sink and table. The eerie aura of the space, supported by the dark lighting, sounds, projected video, and emptiness provided a sense of familiarity with the objects and layout of the room, but without a filling liveliness. The lack of presence—or rather the past presence—infused in this space a sentimentality of memory, a reflection on recollecting who was there, and to an extent still remains.

“I met my friend Elke a couple of years ago and hung out with her a little bit, but I was initially drawn to this story, [as I got] to know her mother after Elke died, and her connection with her daughter was just so strong still—and that was it, I wanted to express that,” Guggenheim said. “I feel like I was really drawn to this whole sort of relationship we have with memories, where memories are very powerful and real to us. And hold so much and yet, like we can’t really access them or experience them because they’re not real—well, they are real, but they’re just they’re not here and we can’t interact with them like we [used to or] that we did with objects around us or people around us. So I was really interested in sort of trying to express that relationship that we have with memories.”

As I walked through the room, my attention was drawn to the objects and then to the projections. After some time, my eyes spotted movement in another projection. While there may be a feeling of emptiness, the movement and images across the different surfaces provide an added dimension and that perhaps there is something existing here out of my view.

“I wanted it to feel like a space–I didn’t want it to feel like you weren’t not absorbed in this new reality,” Guggenheim said. “And so that’s why I wanted to have objects and I wanted people to sort of move around in the space. And the decision to not make one film, but to have one timeline with different projectors, was to make sure that it felt like a space so that multiple things were happening at the same time and there are multiple things that you could interact with moving around.”

In building this space to illustrate memory, Guggenheim found the ability and characteristics of projection and animation to render memory’s realness, and its fictional and fleeting qualities.

“I was really wrestling with how to portray it for a while, but it just seemed like projections [were] such a perfect vehicle because projections aren’t really there, but you’re seeing it,” Guggenheim said. “And I was also really drawn to her relationship with objects when she was…telling me stories. Because I interviewed her for a really long time and her stories that she told me were always surrounded by objects. She’d be like, ‘Oh, like, we’re sitting around a table, we’ve sat around the table so much. This is what happened at the table.’ And so I knew that I wanted to incorporate objects and building an experience, and I wanted to create…a room for memory that is kind of loose and abstract. And then animation. It felt really important to me to have things move, and change. Because how I always picture memories, there’s a temporality to them and it was important to me that things were gone, and then they appear, and then they’re gone again. You just can’t do that with paintings, or drawings, because you’re the one who leaves but the drawings and paintings always stay there. And I wanted what you’re seeing to leave before you do.”

Returning to the gallery’s entrance, and moving into the right section, I encountered bunches of blue and black oyster shells lining against objects within Russo’s “Hiraeth.” On one podium, these blue and black objects sit attached to what may have been some large rocks, buoy, or object along the sea floor. Against the wall, these crafted oyster shells were strewn across the vertical plane, forming a line reminiscent of wave’s swash limit on the sand, and the oysters having been carried by the wave and left onto the shore in cloisters. In making this project, Russo found inspiration from her personal experience growing oysters and her environmental science research.

“In the fall, I conducted a capstone research project for environmental science, where my group mates and I…connected with the Billion Oyster Project in New York,” Russo said. “And we basically tested to see if oysters are effectively filtering out potentially toxic elements from the water in New York waterways, and if they’re actually helping to clean them. Through doing all that work, it really inspired me in my artwork, and I thought it’d be cool to do an art thesis based off of my science research. So that’s kind of where I ended up. Through that whole process, I got really into the idea of repetition that we see in the environment, and this concept of aquaculture and how humans are intervening in natural processes. And so I tried to make my thesis look very organic and real and repetitive, but with a little twist—so everything [has] been made [and] that nothing is really organic, but it looks like it is.”

While initially envisioning a project in the 2D medium of printmaking, through trial-and-error, Russo found sculpture to be more fitting.

“I started out making a lot of prints and stuff. But using 2D spaces didn’t seem strong enough. So I randomly stumbled across [some] old Crayola Model Magic in my stuff. I ended up using mostly that for the project, and I would mix different paint into each little bit. Each shell that ended up on the wall is individually handmade, and then stuck together to make the whole creation. It was a very methodical process, very slow—it was just a lot of like mixing paint into clay, making little bundles. I also used a lot [of] ropes that I wove together myself. And there’s a bunch of different creatures. I also had like some wax corals that didn’t make it and some resin oysters.”

Moving onward, the forest came into view, with Eustace’s “Trees” featuring these large tree trunks hanging from the ceiling, split into sections, yet positioned as if almost still whole; the outer bark remained raw and the inner surface was stripped and empty, coated with metal. While walking between these trees, the light from the window reflected off of the metal interior, providing a reflective glow around the gaps between the sections.

In initializing their thesis project, Eustace wanted to find a way to imbue their passion for the environment in their sculpting.

“I wanted to find something that I thought reflected things that are really important for me in life, or, like reflect how it feels to exist,” said Eustace. “And one thing that’s always really prominent for me is just broadly the environment. And the problem was…that it’s such a broad issue; it’s kind of impossible to just make sculptures about environmental…degradation, catastrophe, climate change, global warming, whatever. In a broad sense, it’s hard to like, find one thing to make sculpture about. So what I narrowed it down to is…how can I talk about the loss and change that’s occurring, that’s tied to human existence or tied to the human hand. And I’m also an environmental studies double major, and I took a class in which I learned all about the forests around Wesleyan and Middletown, and there’s this process, mesophication, in which oaks and pines which are cultural and ecological keystone species are being outcompeted and are losing their ground in our ecosystems—and that’s because of both human [intervention] and lack of human intervention. So it’s…to me an issue tied to the human hand and the environment, and I wanted to make sculpture about that.”

Eustace remarked on the difficulty of the process, learning how to fulfill his vision, and finding the right sources, materials, and people to help bring them together and install them.

“This type of this way of processing lumber in…the sawmill industry [is] called a cant cut,” said Eustace. “It’s when they take the outside of the tree. And each of those trees, those sections that are hanging are the sections that were going to be sliced for lumber. They take these live edge slabs off of the section of tree and then you’re left with a huge rectangle of lumber that they then cut down—and that’s what you would see at Home Depot or that people use for building…. And so I had to go and find a sawmill that would do this cant cut and give me the live edge slabs.”

Beyond the forest, a constructed form of black rope divided the space. Kaubisch’s “delimiter,” featured a few long strings of rope that darted around in sharp right angles to outline the air. These divisions were across the ground as well as the vertical area, allowing me to see an apparent barrier, despite there being none, and questioning whether one should, or could, move under, or through it.

At the end of this section were the backdrops and puppets used in Levine’s “Tender Tales of the Doublerealm.” Spread out across the back three walls, the elements of the puppet performance were placed around the given space: on one side, a painting had an interactive shadow puppet show projected onto it, along the back wall hung other painted backdrops, and other puppets and poetry filled the corners. Beyond these elements, a video screen played a recording of the actual project, the puppet show itself.

In creating this puppet show, Levine found a way to blend their background and interests in poetry, puppetry, and fantasy to build a narrative production and a world for these pieces to interact, carry her message, and spring to life.

“When I started to come up with the idea, I was looking for a way to ideally combine the poetry and weird fantasy stuff,” Levine said. “I thought that just doing paintings was a little bit boring to me and didn’t feel like it would be fun enough to carry me through the year…. I wanted to make a project that was really for me, and what I enjoyed doing because…if you’re spending all of this time and energy on something, you want it to be something that’s really enjoyable. When I was younger, I worked at this theater camp, where we learned to make giant puppets, which I thought was really fun. I think the most fun thing about making art is problem solving, and coming up with creative solutions and stuff. Whether I’m doing a drawing or painting and figuring out how to represent something realistically, or figuring out how to make something move, or something stand up, I really like being able to make things that are functional. I feel like puppets are the epitome of endless opportunity to just make weird things. There’s just so much freedom and everything.”

While Levine had made puppets previously, this project required added complexity through new methods to construct the puppets to look and function as desired, as well as to organize their story and the live performance.

“I decided I wanted to make puppets and then I was trying to figure out what kind of story there would be. And I initially didn’t even really want to do a puppet show,” Levine said. “I just wanted to make the puppets and have them be able to move. And then my professors were like, ‘well, if you’re making puppets, then you have to have a puppet show.’ And I was like, that seems like a little outside of my comfort zone because I’m not a performer or a director, I’m just a writer and a visual artist. But that was where all of the other people came in…. I made all the puppets and stuff, but I just, I have no idea whether it would have come together without them. And it definitely wouldn’t have come together as well.”

While watching the puppet show, I found it striking from the mix of the backdrops, the roving puppets of human-faced fish and birds circling around during many of the scenes, to the fantastical design of the wolves and the double mother (two women connecting through a shared pregnant belly). The artistic style, the visual performances, a fantastic soundtrack, and the abstraction of poetry read during the sequences fostered an absorption into a new world I entered as a viewer, and yet this surreality remained grounded and connected to the tangible experiences within my mind.

“I wanted to make art to make people understand, or make myself understand, what it is to leave reality,” Levine said. “I wanted to be able to throw people into another world by force, and have them experience what was going on in my head.”

As I left Zilkha, I reflected upon the art I just viewed, finding myself connected to these pieces as each student’s exhibition absorbed and brought me to a different place and allowed me to meditate on personal experiences with loss, memory, nature, and imagination. While each solo exhibition was neatly sectioned within the gallery, there was an interesting interplay between them due to this commonality of environment and space—whether in the natural world or the fantastical. This solo yet shared exhibition was as much about this community of artists behind the work as the pieces themselves.

“It doesn’t necessarily feel like we’re artists randomly placed in a gallery,” said Levine. “It feels like these are people I’m really close to and we have built a project together. And like we all get to stand in this giant room and be with our life’s work.”

Andrew Lu can be reached at ajlu@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply