A polar bear pets a lab-grown chicken. Two soldiers fall in love and find out they are twin brothers. The Global Peace Conference is run by crying babies. The last man on earth hears a robotic voice asking him to repent. No, you’re not tripping: the apocalypse is coming.

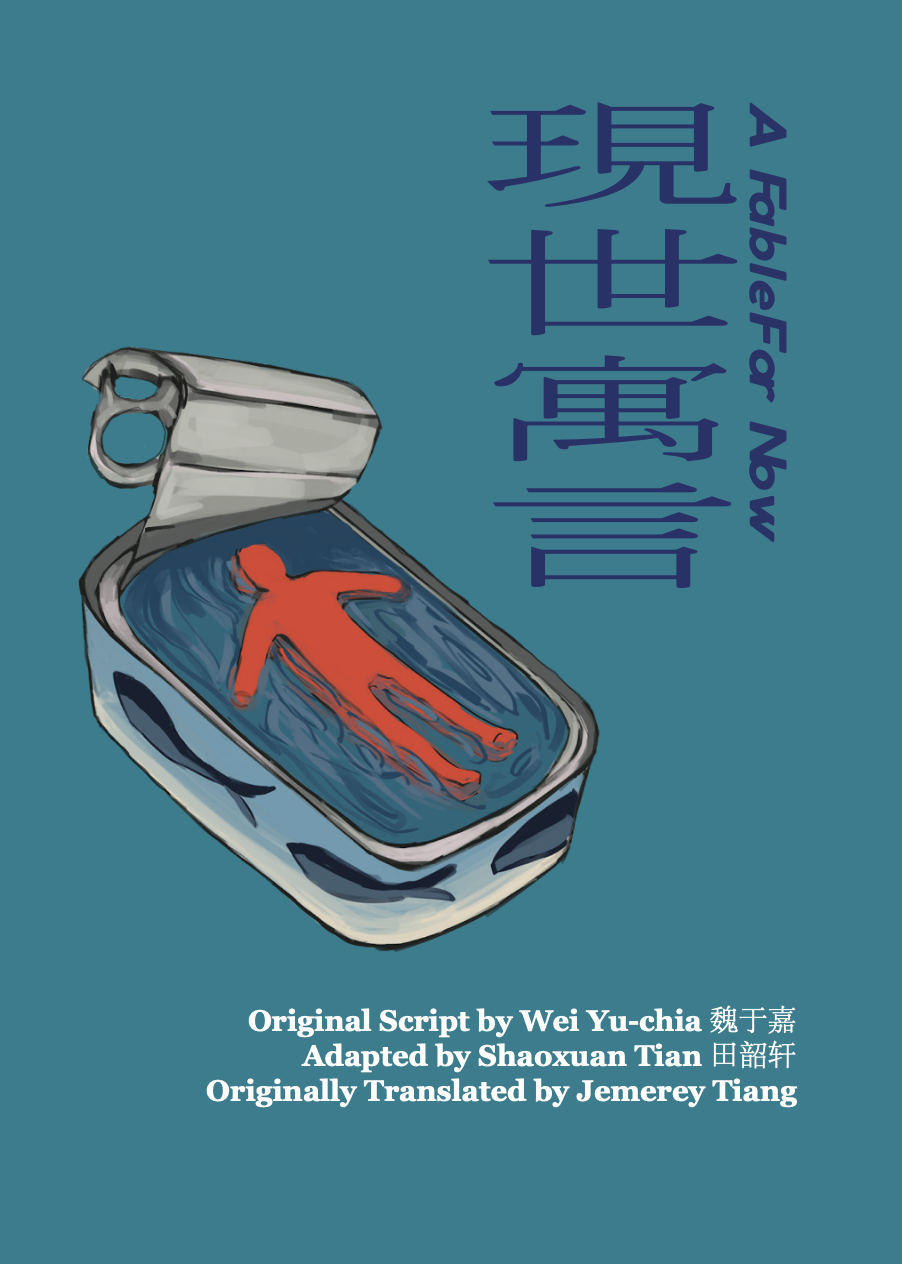

Or so it goes in “現世寓言” (“Xianshi Yuyan,” or “A Fable for Now”), a dark comedy written by Taiwanese playwright Wei Yu-Chia. Co-directed by Echo (Shuowen) Shen ’24 and Scarlett (Chenchen) Long ’23, the Mandarin play was performed in West College (WestCo) Cafe on Friday, April 7 at 8 p.m. and on Saturday, April 8 at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m., opening the Spring 2023 season of Spike Tape.

Written in 2013, the play imagines a world facing imminent destruction through seven wild, nonsensical scenes. The first scene, titled “Do you know that polar bears die of cold?” is a conversation between a man (Xingyan Guo ’25) and a polar bear (Hongyuan Yang ’23), who share a cigarette. The second scene, “The Bear and the Duck,” sees a panda (Liang Liang ’26) and a duckling (Tina Han ’24) lamenting their lives as zoo animals.

Further accentuating the absurdity, the following scene portrays political leaders as loud babies fighting incessantly in “The Summit of Infants.” Then, scene four takes place at the war zone between Beiguo (North Country) and Nanguo (South Country), where the two last remaining soldiers, one from each side (Spencer Jiang ’26 and Isaac Platt Zolov ’26), decide to call a truce and fall in love before discovering they are actually long-lost twin brothers.

Scene five, titled “Sodium Cyclamate”—named after the food preservative—brings us back to the polar bear, who is now the boss of a fish canning factory, overseeing unhappy workers and a lab-grown chicken. In scene six, “Zoo Story,” the animals attempt to escape the zoo. And finally, we hear a heart-wrenching monologue from the last human on earth (portrayed by Guo) in a culminating scene called “Great Harmony.”

It is not difficult to notice the real-world inspirations behind all these apocalyptic events on stage. In a note to Teaching Fellow in English Jeremy Tiang—who translated the play in 2020 and offered his translation to the student theatermakers—Wei explained why she wrote the play.

“[In 2013,] there were all the debates about same-sex marriage in Taiwan, tension over nuclear testing between North and South Koreas, food safety issues of China’s paper buns and fake eggs and Taiwan’s cooking oil,” Wei wrote. “Global warming has starved polar bears and made me ashamed as a human being, [alongside other problems like] migrant workers and low wages.”

Similarly, Shen also pointed to China’s sociopolitical context in late 2022 as the reason why she wanted to put up the play.

“We started this process because half a year ago, China was in a very chaotic situation [about which] I receive all kinds of information and translation every day from all kinds of social media,” Shen said. “And it gave me a good impulse to respond, or at least do something because I’m physically so far away from China, and there’s not much that I can do. And the sense of loss of this connection is something at that point I really wanted to change. That kind of discomfort actually drove me to this production.”

Doing a Mandarin production was also a way for Shen to reconnect with her mother tongue.

“I think part of this project is also creating a safe space,” Shen said. “I know Mandarin is like home to me, but I’m losing it. And it’s also a way of trying to get it back to me. Because before, I was very used to reading and writing in Mandarin. I felt like we were once good friends—me and the Mandarin language—but after coming to the States, things got a bit tricky here. It’s a way of trying to mend our relationship in a way.”

Long emphasized the show’s historic significance as the University’s first ever Mandarin theater production.

“I remember when I was a freshman, Eva Lou [’18] wrote somewhere that her biggest regret at Wesleyan as a theater major is that she has never had an opportunity to make a Mandarin production happen on this campus,” Long said. “And that, for some reason, just stayed with me throughout the course of my four years here.”

Long described feeling alienated while doing theater at a predominantly white institution. According to Long, theater spaces especially tend to be occupied by white students. They talked about their original play about an Asian family, “The Unwanted Siblings,” being denied funding by the now-disbanded Second Stage.

“Especially when I was an underclassman doing theater, I always felt othered and to some extent excluded from the main theater scene and that I didn’t have the power of telling my own story,” Long said. “[I felt] loneliness. Growing up as Asians, we didn’t have this habit of going to theater or making theater. Theater was never a thing back in China or for a lot of Asian students. So I wanted to create this space on this campus for Asian students or Chinese international students to participate in a theater production, to make theater, and let them know that it’s possible and actually not that hard to do.”

Echoing Long’s sentiment, Shen highlighted the challenges of being a Chinese international student and a theater major student at the same time.

“I often find myself in an eight-person class where I’m not just the only Chinese but also the only Asian in the class,” Shen said. “And we sometimes have to read our work out loud, but the people around you are all native English speakers. That can be very intimidating.”

The two directors met in Assistant Professor of Theater Katie Brewer Ball’s class THEA235: “Writing On and As Performance” last fall and decided to collaborate on something special. They reached out to Tiang, a translator of Mandarin plays, for script suggestions, before settling on Wei’s apocalypse story.

“We just liked the story itself,” Shen said. “Even though it’s a dark comedy, it’s approaching a lot of social issues in a very playful way. But at the same time, it’s very deep. And that’s something that I wanted to do, because I don’t want to be very serious. And this play would be a torture if it were all serious for two and a half hours. And I think there’s something important to make people laugh, but at the same time, knowing how terrible it is.”

Tiang also told The Argus about his love for Wei’s script and how he came across it in the first place.

“Literally, I was just going on the website [of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature], reading all the winning plays [in its annual Taiwanese literature competition], and [“A Fable for Now”] really jumped out to me because it was so inventive,” Tiang said. “It was like nothing I’ve seen before; it dealt with so many social issues, but not in a didactic way. Each scene jumped to a completely different thing. And yet, the whole play felt coherent to me. So as soon as I read it, I was instantly interested. It felt like something that I needed to translate, because it was something that was missing from the English language theater.”

Tiang then managed to get ahold of Wei’s email address and asked to translate her play. Upon hearing that Tiang would do it for free, Wei happily agreed. During the translation process, Tiang worked with a director to stage two readings of the play—one in London and one in New York—with a British cast and an American cast respectively.

When Shen and Long asked him for suggestions of plays to stage at the University, Tiang shared a few scripts that he thought would be interesting and also gave them his translation to use as a basis for the supertitles.

“After they had selected the script, they asked a few questions,” Tiang said. “And they also asked Wei Yu-Chia for permission to make some changes, which she was very happy to give because she is very open and collaborative.”

With a script in hand, the next task for the co-directors was to recruit Mandarin-speaking actors.

“When we walked on the street, we’d literally just go to someone that we thought that they speak Mandarin, or just be like, ‘Would you be interested in acting in this?’” Long said.

Although most actors in the show are native Mandarin speakers from China, Zolov, who delivered an electric performance as one of the brother lovers, is not.

“He is a Mandarin learner, which we are also very proud of,” Shen said. “I feel like another purpose of this whole project is to open up the conversation beyond Mandarin speakers. So we actually wanted to recruit basically people around the world with different backgrounds, as long as they are comfortable in speaking and performing in Mandarin.”

The directors also highlighted that the majority of the cast were first-time actors, emphasizing the goal of making theater more accessible to international students at the University.

“When I was a freshman, I felt a little isolated in campus-wide productions, so I wanted to reduce these obstacles as much as possible,” Long said. “I wanted to create this atmosphere for [our first-time actors] to get to experience the joy of making theater in an environment they can feel comfortable in, and therefore invite more and more Asian students and international students to do theater.”

According to the creators, the play was produced by Spike Tape and supported by the College of East Asian Studies (CEAS).

“I have to give full credit to Spike Tape, because they actually trusted us and believed us in doing this whole production, and the amount of support from them was incredible,” Shen said. “We gained a lot of support from [CEAS] as well.”

Shen acknowledged the challenge of working with new actors but expressed gratitude for the diverse perspectives they brought to the show.

“It’s a pleasure working with them, even though they are first-time actors,” Shen said. “Because they are human beings with their own insights and their own backgrounds, and also with different academic backgrounds, which helped us a lot. I know we have actors [majoring in] Environmental Studies, and this play—a large part of it is about environmental issues. There [were] problems, but I feel like the value they brought to us far [exceeded] the problems.”

Wei’s script is known as a closet play, which means it is not intended to be performed on stage. It features fantastical stage directions like “A chicken explodes and its meat is eaten” and a monologue that goes on for 50 pages. To complement the script, Shen and Long made extremely impressive directorial decisions in the performance, with the dreamy lighting and otherworldly set design, which gave the show a surreal feel that was not found in the original text.

“I’m pretty proud of the set,” Shen said. “The backdrop had this plastic-ish texture that collaborated with lightning really well, so there was this very fake-ish and dramatic atmosphere going on. And plastic itself is like a perfect symbol of modernization, and that was inspired by part of the script where the two characters are discussing how pretty the sunset is, but it’s actually due to the pollution. And another prop, the TV, is also a symbolic source of information.”

Shen also talked about the production team’s attention to detail.

“All the factory cans were ‘handmade,’ because we painted all the cans in white, and our costume designer actually designed the very specific can labels,” Shen said. “And we printed out stickers to [put on] the cans. And also there’s this whole bunch of clocks, symbolizing time, being attached to the shelf, because the following scene is the apocalypse of the world. I think of theater as a collaborative language, where all different sources and types of art should all contribute to storytelling in a way.”

Long brought up the tsunami scene of the script, which they were able to create with a very simplistic set.

“I’m just gonna say I’m very proud of the tsunami scene,” Long said. “That whole design of the visual image with only a chair.”

To highlight the open collaborative relationship between cast and crew, Shen mentioned the song “ff” by the recently deceased Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, used in the show upon Guo’s suggestion as a personal tribute to his work.

“There was a part in the show where the characters were talking about the aurora and also how beautiful the sky is,” Shen said. “And the background music is ‘ff.’ It’s a big part of Sakamoto’s music project, especially in experimental music, to explore this idea of modernity in Japan and how it affects the environment, which also goes back to the play itself.”

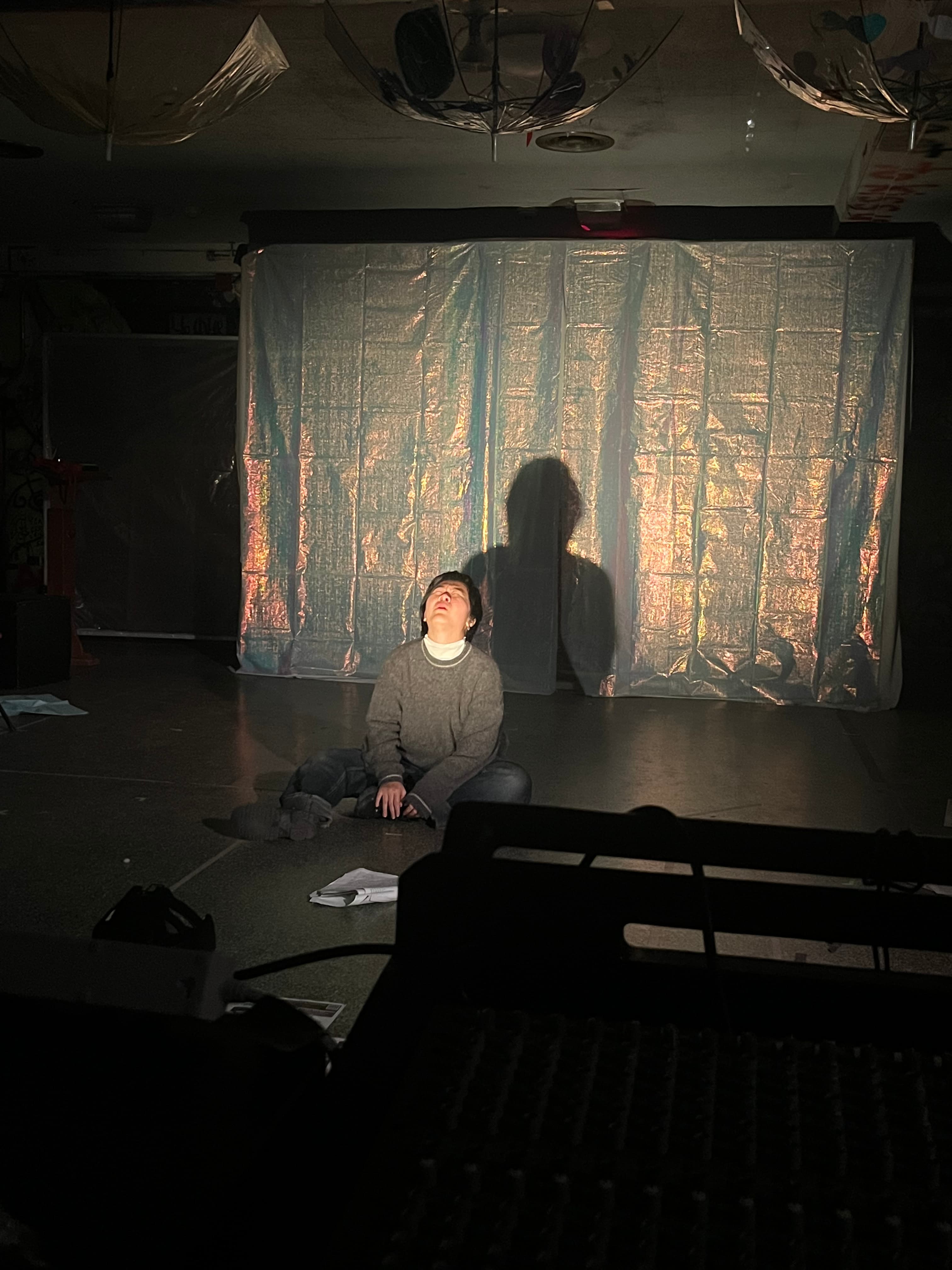

The final monologue, which is not accompanied by much stage direction in the script, was made much more compelling by the directors’ creative choices. To start off, they cast Guo, a woman, in the central role of a misogynistic man. The gender inversion reminded me of the crossdressing performance that is extremely prevalent in traditional Chinese theater and added a poignant critique on gender relations in Chinese society. The toxic projection of male desire in the original script was wittingly turned into an expression of female sexuality, as Guo enacted a masturbation sequence under dim lights.

“The last scene, a long ass monologue, was intimidating, I believe, to a lot of directors, but that was one of the reasons why I wanted to choose this play—because I was fascinated by this monologue,” Long said. “And because it’s so long, and the whole time it’s just [Guo] herself on stage speaking, how would the audience stay with us and distinguish between the beat changes? We had a long exercise just to analyze the beat. And then we had different staging. And also, I feel like the lighting creates a lot of dynamics in that scene. I also liked the design at the end, where the ensemble members came in to create that gay bar scene and also to create that circle where they say the lines together.”

The ensemble’s chanting in circles was reminiscent of a Greek chorus. Guo stood in the middle, leading everyone in saying the lines and creating a dynamic asynchrony, which Long was very pleased by.

“I actually liked how when they said the lines, [they were] not perfectly synchronized,” Long said. “Because it was all about that moment, the burst of emotions. All the frustrations are real, even when the lines don’t perfectly match.”

Furthermore, the hilarious lovers-turned-brothers scene capitalized on the language barrier between Zolov and Jiang to present a relationship that transcends differences.

“At one point, we asked [Zolov] to speak English, just for a bit,” Shen said. “Because [the characters] were from different countries but were actually developing a very strong relationship and a genuine bond between each other. So even though sometimes [Zolov’s] manner and language could be a bit off, I think it’s their attempt to actually come together.”

The two evening shows were accompanied by English supertitles, created by Hao Fu ’26 with input from Zirui Zhang ’26 and Jiang based on Tiang’s translation and Shaoxuan Tian ’23’s dramaturgy. Both Shen and Long expressed their gratitude for the hard work of the supertitle designers.

“All the credit goes to [Fu],” Long said. “It was a lot of pressure on just herself, one person, to run two hours of the show with over 1300 slides. So I really appreciate her. She’s our superhero on this. Otherwise, I don’t know what we would do.”

Shen agreed, echoing Long’s sentiments.

“The reason why we had [supertitles], after all, for the two night shows was we didn’t want the audience to be intimidated by not being able to understand anything, but it was actually so hard to do it,” Shen said. “We had run crews creating these PowerPoints for a whole week. It was much harder than I thought it would be just because of the length of the script.”

However, even without the supertitles, the language of theater was universal. The directors shared that there were non-Chinese-speaking audiences at the matinee show, some of whom even came back to see the show twice.

“[Some of my American friends] called it ‘the best student production they have seen at Wes,’” Long said.

To Shen, it was very important to have the matinee show not subtitled.

“I’m tired of treating English as the default language in this country,” Shen said. “I feel like they should maybe have a taste of what our lives look like. Like, we don’t have this obligation to translate everything for you. I think we were aware of submitting to this hierarchy.”

Reiterating the transcendental power of theater, Shen alluded to her theater experience in high school.

“In my high school, we had this theater festival, which was in Mandarin, but I had foreign teachers who came in and were able to understand most of the stuff,” Shen said. “I think there’re so many things that transcend language itself, which is also part of the purpose, because even though all these social issues are grounded in Taiwan—and after our dramaturg’s adaptation, maybe grounded in mainland China—they still apply to everywhere. I don’t think Americans would have trouble understanding the critiques and emotions we were trying to present in the production because it’s just so universal.”

Long agreed on theater’s universal appeal and expressed their wish for more non-English productions on campus.

“Definitely, there should be more,” Long said. “I don’t want to be the only one. Because we’ve proven that it not only worked, but people loved it. We proved that there are so many talented Mandarin speaking actors on this campus who are eager to do more theater. And second of all, we found that we don’t actually need the subtitles to present it. Theater itself is an excellent universal language. And subtitles work, right? So, either way, people will be able to understand. We’ll definitely add more diversity to the theater scene on this campus.”

Tiang also hopes for more Mandarin shows to come.

“I’m surprised it took this long for a Mandarin-language production,” Tiang said. “I’m glad it’s finally happened, and I hope it’s not the last.”

The turnout exceeded the creators’ expectations. Not common for student theater on campus, amongst the audience were Assistant Professor of Theater Katie Pearl, Associate Professor of History Ying Jia Tan and his family, Associate Professor of Music Su Zheng, Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies Scott Aalgaard, Japanese and Chinese foreign language teaching assistants, several alumni, and friends of the creative team, some of whom came all the way from New York City to see it.

According to Shen, the final show sold more tickets than the number of seats available, so they had to add more chairs and rearrange the layout of the space. She also gave a shout-out to the audiences who came to see the show happen.

“I need to credit our audiences so much, because you actually need to be brave to step into this space and commit your time to this production,” Shen said. “I’m so happy to bring my professors whom I’ve never seen outside of the classroom into WestCo Cafe, which is a very Wesleyan space, instead of a standard proscenium stage like the [Center for the Arts] Theater or Patricelli ’92 Theater. It’s a space that is very intimate and very interesting. And I’m also glad to bring a lot of Chinese international students who weren’t so engaged with the campus at all to WestCo Cafe for the first time.”

For the directors, theater is all about creating space and memory for community building.

“I feel like there is a purpose, and it’s valuable to create collective memory,” Shen said. “The memory itself will be so powerful as well, because after 20 or 30 years, we can still talk about the experience of being in the space together watching the production. The experience is so important for everyone, basically, regardless of nationality, whatever.”

Long similarly mentioned the importance of sharing a space with other Mandarin-speaking theatermakers and bonding over shared cultures.

“A lot of times, when I was in other shows, I sometimes didn’t even know half of the pre-show music or the curtain call music,” Long said. “But this time [we could play] a lot of great Mandarin songs. It just makes me feel like, this time, we’ve got this chance to do something that we understand, and it speaks to us.”

Shen shared how touching it was for her to see the audience mingle every time the show ended.

“I think this whole production itself is trying to promote conversation, which I’m so glad that it actually did,” Shen said. “Because after each production I see professors and friends lingering around the space, talking about either the acting or the content of the play. It goes back to the point about community building. This is how theater brings people together.”

As a graduating senior awarded with a full-tuition scholarship to pursue a Master’s in musical theater at New York University, Long is determined to make the theater scene more inclusive for all.

“In my musical ‘Crush! Crush! Crush!’, we’ve already started to incorporate Mandarin elements,” Long said. “There is one scene about language barriers where we have a fair amount of Mandarin. I definitely see a lot of potential in multilingual theater productions, but I also see there will be a lot of potential obstacles that we might face. The K-pop musical, for example, already received criticism for using too much Korean lyrics. But still I feel like multilingual theater is the next big thing.”

“It goes back to the idea of theater as real-life performance, and this art itself has a vitality and life inside of it,” Shen said.

Guo shared a similar sentiment.

“I [once] wrote to myself: ‘I have an instinct, that I can trust theater like how I trust my lover. Inside a space, a story, a human, I could be vulnerable and alive,’” Guo wrote in a message to The Argus. “This time living in ‘A Fable for Now,’ my trust in theater has grown and branched out. I trust my mother language dancing on the tip of my tongue in my alienated body. I trust friendship and collaboration that transcend where we’re from and lead us to imagine futures. I trust audiences who listen deeply and carry the moment we spent together in the theater out to life.”

And to me, this life is all we need in a world where everything goes wrong.

The staged reading of Long’s original musical “Crush! Crush! Crush!” will premiere in the Ring Family Performing Arts Hall at 8 p.m. on Monday, May 8.

Echo Shen is a Layout Editor for The Argus.

Sida Chu can be reached at schu@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply