On Wednesday, Feb. 17, Assistant Professor of Art and Luther Gregg Sullivan Fellow in Art Ilana Harris-Babou held an artist talk in the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery for her exhibition “Liquid Gold.” A multi-media installation that focuses on the history of breastfeeding for Black mothers, “Liquid Gold” gets its name from colostrum: a yellowish, nutrient-filled liquid that mothers produce for a short time postpartum before they begin producing breast milk.

To contextualize “Liquid Gold” among her oeuvre, Harris-Babou first introduced the audience to “Decision Fatigue,” a video in which her mother tells viewers about her “beauty routine” while applying makeup. As she walked through the steps of her absurdist routine—which involved covering her face in Cheetos—Harris-Babou’s mother discussed the toll of breastfeeding on the body.

“When you breastfeed, your life force is drained from you,” Harris-Babou’s mother said. “It’s drained. It’s being taken away. It’s metaphysical, in fact. Eventually I’ve been told that it doesn’t cause that much of a physical reaction on your part in terms of pain, but my personal experiences have been to the contrary. Your breasts become very, very swollen and hard, and tender. The nipples become crusted sometimes and they invert. It causes, for me, a frustration that I just can’t deal with.”

As a prelude to “Liquid Gold,” Harris-Babou also introduced “Long Con,” another project that examines how consumerism frames structural inequities as individual decisions. A video from the installation showed footage of Dr. Sebi, a controversial healer who claimed to be able to cure cancer and AIDs with herbs and an alkaline plant-based diet. By featuring Dr. Sebi, the artist highlights the false promises of the modern wellness movement which boils down a “healthy” lifestyle into a series of individual choices while ignoring persistent inequalities.

Individual choices as they relate to breastfeeding also lay at the heart of “Liquid Gold.” In the video portion of the installation, Harris-Babou’s mother and older sister discussed their differing experiences with breastfeeding. While the artist’s mother found the experience of breastfeeding to be painful and decided to feed her daughter formula, her older sister felt empowered, as doing so allowed her to save her daughter’s life.

“I sort of feel the decision-making was more about circumstances and it was more of her health condition made the decision for me,” Harris-Babou’s sister says in the video portion of the installation.

In the video section of “Liquid Gold,” the disembodied voices of Harris-Babou and her family members can be heard as milk bubbles and froths on screen. The foaming milk invites viewers into Harris-Babou’s surreal world, an intimate space she harnesses to explore personal anecdotes. In one particularly light-hearted moment, Harris-Babou’s older sister recalls adding chocolate syrup to her sister’s formula, after which the artist refused to drink it any other way.

Sound, specifically the singing of lullabies, plays a vital role in connecting family stories of breastfeeding to the stark history of Black maternal breastfeeding. When conducting research for “Liquid Gold,” Harris-Babou reached out to her mother and sister to hum lullabies they remembered. The artist’s mother hummed “All the Pretty Little Horses,” a lullaby her mother sang to her when she was young. During this time, Harris-Babou’s mother was growing up in a Connecticut mansion where her mother cared for the household’s white children. Many historians believe “All the Pretty Little Horses” originated in the South, where enslaved Black women sang this lullaby to white children in their care while they were forced to leave their own children uncared for. After learning about the song’s history, hearing Harris-Babou and her family members sing “All the Pretty Little Horses” was unsettling though still sweet. By humming the lullaby, the artist and her family evoke the song’s complicated past and honor Black mothers of the past and present.

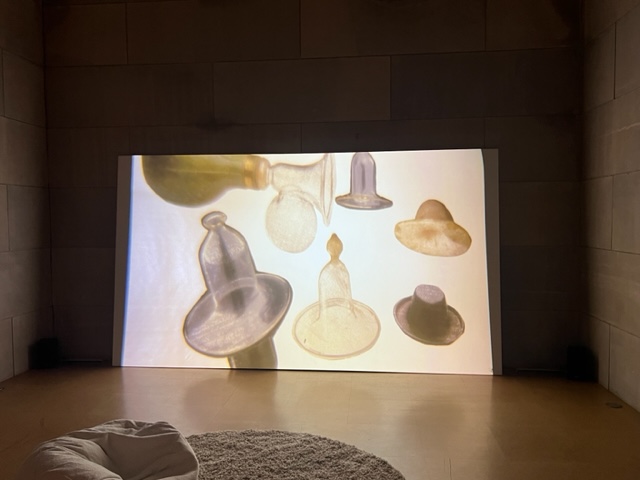

The sculptural portion of the installation only enhanced the surreal world Harris-Babou fashions in “Liquid Gold.” In a passageway leading up to the video portion of the exhibit, ceramic objects Harris-Babou designed gleam on a canvas-covered table. Among them were nipple shields, glass objects that mothers used to breastfeed in the Victorian era. Tubes snaking around and through some of these objects transport a white liquid that pumps in and out of a large reservoir on the table. In this evocation of breastfeeding, and throughout the exhibit, Harris-Babou demonstrated her great power as an artist: to elevate the ordinary into unreal and thought-provoking dimensions.

“I take a viewer along that journey with me and go from something seeming familiar and safe, to some kind of grand narrative seeming authentic, to realizing it’s totally weird,” the artist explains in promotional materials for the exhibit.

Ilana Harris-Babou’s brilliant exhibit is not to be missed. Go see it at the Zilkha Gallery before it closes on March 3.

Ben Togut can be reached at btogut@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply