c/o Social Science & Medicine

Last week, when I ran into one of my housemates at the gym, I realized that before this, we had never worked out in the same space as one another. Most mornings, as I make my way out the back door, I notice her exercise mat spread across our living room floor, catch a whiff of a freshly lit candle, and hear the calming voice of an online yoga instructor. It’s a sharp contrast to the sight of scattered dumbbells, the smell of sweaty bodies, and the sounds of crashing weights that I encounter when I arrive at the fitness center every day. Yet the chaos and disorder that comes with working out at a public gym—particularly one as overcrowded as Wesleyan’s—has never really bothered me. If it did, I probably wouldn’t spend as much time as I do lifting weights or tidying them up while on shift. But the fact that I enjoy being in this space so much doesn’t necessarily mean everyone else does.

Upon reflection, I know that much of how I feel toward the gym is tied to the way I was first introduced to it. My transition from working out in my room to working out in front of complete strangers was more or less a smooth one, something that I owe in large part to my older brother. I was around 15 years old at the time and desperately craving a break from the world of competitive sports. This just so happened to coincide with the beginning of my brother’s own journey into health and fitness. So with my mom’s approval and under the guidance of my brother, I took the pocket money that I had spent months saving and purchased a membership at my local leisure center—think of it as the British equivalent of your local recreation center. To begin, I started working out at the gym just a few times a week, on the days when I didn’t have netball practice. For a while, I was my brother’s gym buddy who spotted him on difficult sets, imitated his lifting form, and encouraged him to lift heavier. But I was also his student—a gym novice who quickly learnt the ins and outs of gym etiquette, the nuances of strength training, and the truly transformative effect that working out has on both the mind and body. It’s thanks to him that I appreciate what it means to push myself to failure, that I know to always put my weights away—if you’re someone who doesn’t subscribe to this, it would be great if you could start—and perhaps most of all, that I feel confident and safe within this space. Had my first interactions with gym culture not been so positive, maybe I wouldn’t be the “gym rat” that my housemates jokingly describe me as today.

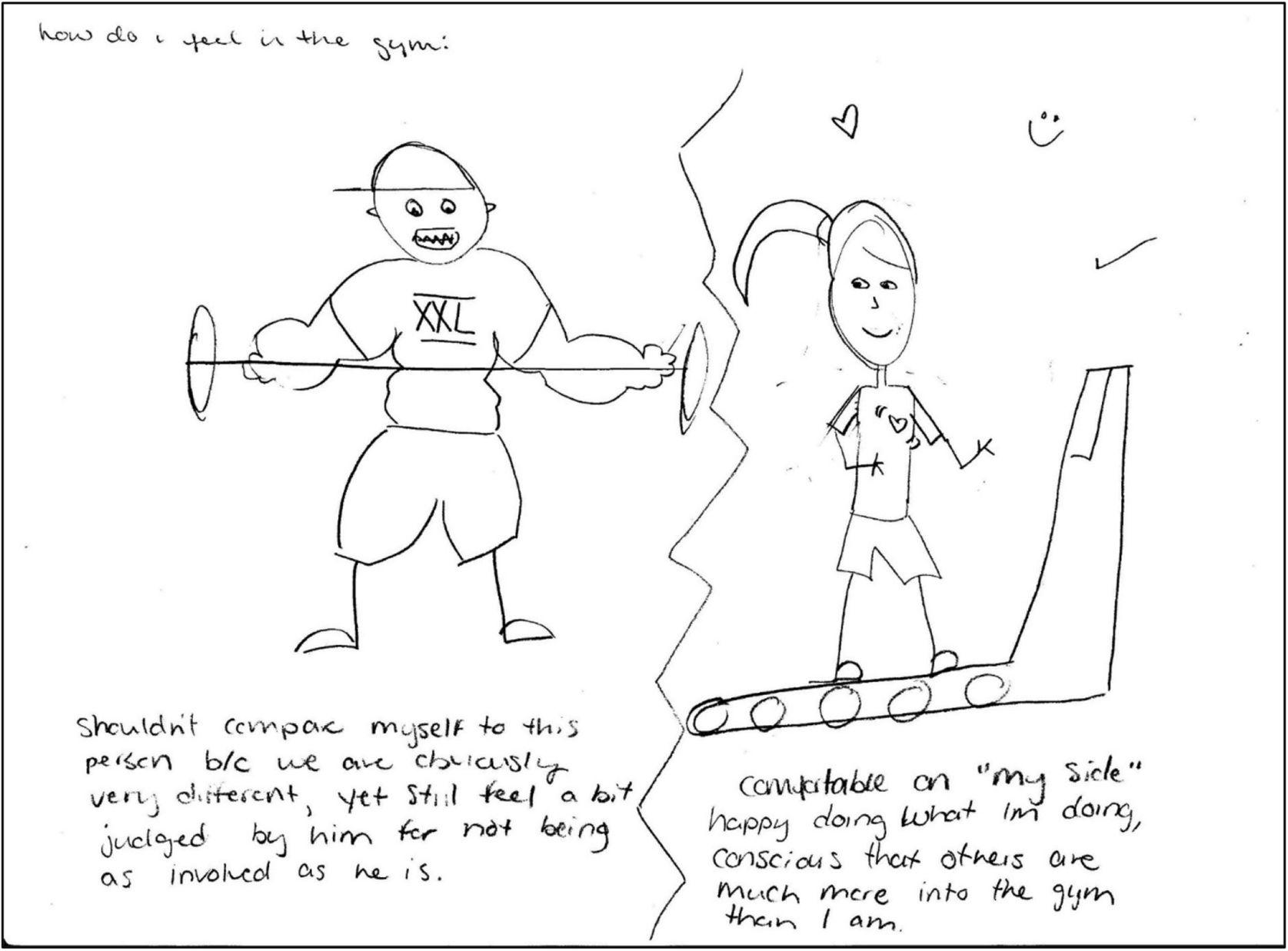

However, I know that exercising at the gym, or even the very prospect of it, is far from a confidence-boosting experience for many women. Instead, more often than not, women find themselves restrained by rigid and harmful gender norms which seem to permeate these spaces. In one recent study, conducted on 1,000 people across the U.S., roughly 65% of the women surveyed said that they avoid the gym out of fear of being judged, compared to just 36% of men. I have many friends, including my housemate, who share these sentiments, and to be quite frank, it makes a lot of sense. When you enter a space like the gym, full of people who appear to know exactly what they’re doing and have the physiques to prove this, it is very easy to feel like you don’t quite match up. Add the pressure that women are now under to have the biggest ass, the most cinched waist, the thickest (but not too thick) thighs, and the most toned arms (but not “too bulky”), and lo and behold what you end up with are stats like this.

Even if women aren’t completely put off from going to the gym, how they act within this space is telling of just how deep and embedded gender conventions run. According to health geographer Stephanie Coen in a report discussing the role that gender plays in shaping social environments such as the gym, an overwhelming number of women report that they “self-police” their behavior in gyms in order to stay within the confines of what is perceived as “normal” for their gender. Indeed, while male gym-goers may avoid using certain equipment deemed to be “too feminine,” their female counterparts are often concerned with “taking up too much space” or making too much noise.

“What was so embedded in the environment of the gym was that a lot of women talked about ways they would minimize their consumption of time and space in a way they didn’t want to get in the way of someone else,” Coen said in an interview with Phys.org.

Despite the surge in body-positive fitness social media accounts that encourage women to push back on the idea they should stick to cardio, a long history and culture of men dominating these spaces and setting the standard for what it means and looks like to be fit and strong has either pushed women out of gyms entirely or left them feeling like they don’t belong. Now, by no means do I believe that men shouldn’t work out at the gym, nor am I necessarily in support of segregating fitness centers. It was only two years ago that the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled that dividing gyms in such a way would violate state law, which prohibits discrimination based on gender. Maybe I’m being naive or blindly idealistic, but I am also not convinced that we are—or rather should be—at the point where men and women can’t exercise comfortably and safely alongside each other.

However, as a woman who once lacked any understanding of how to lift correctly or what to do and not do in a gym, I know how crucial it was for me to realize, over time, that I had every right to exercise in the same space as those who clearly had the expertise I sought to gain. Perhaps having my brother by my side as I was thrust into what is fundamentally a hypermasculine world equipped me with the ability to look past the condescending stares, to ignore the critical comments, and to politely reject offers of “training support” from opportunistic male gym users.

But just because the negative interactions and experiences that I’ve had haven’t kept me from returning to the gym altogether, that doesn’t mean they haven’t left me feeling extremely uncomfortable. When I was abroad in Paris, there was one occasion when a man took it upon himself to add plates to my barbell while I was resting.

“You can go heavier than that,” he said.

I laughed nervously and carried on with the rest of my workout. Five minutes later, and after he had watched me complete my entire set of squats, he returned and began probing me incessantly on my ethnicity. During another workout, this time at my gym in the U.K., a stranger approached me as I moved some equipment across the gym floor. Before I could even say no, he’d taken the bench from my hands and was asking me where I wanted it.

“We should train together some time,” he said, nearing closer to me.

I took some very blatant steps back, declined his suggestion, and put my headphones back in.

The fear of harassment and intimidation is a shared one among an alarming number of women who exercise in public spaces. In 2021, Women’s Running UK reported that 76% of women surveyed felt uncomfortable exercising in public due to harassment. These concerns led many to avoid going to the gym at night, to only train their lower bodies when they weren’t alone with men, and to modify their clothing depending on what time they went to the gym and who was there.

Women who want to exercise in a space like the gym shouldn’t have to take these kinds of worries into consideration. The most that anyone, regardless of their gender, should really be focused on when they enter the gym is getting in a good workout that leaves them feeling great. At least that’s my aim when I walk into the Wesleyan gym on a Monday morning, often sleep-deprived and unprepared for my first of five lifts that week. Maybe some part of me adopts this mindset because it’s easier to pay attention to training hard than it is to worry that my body is being scrutinized, that my form is being analyzed, or that I too am taking up too much space. But if I’m honest, I think that there’s an even larger part of me that refuses to concede to the implicit boundaries placed upon my femininity, and it is because of this that I will keep on lifting weights and I will carry on taking up as much space as I feel like.

Tiah Shepherd can be reached at tshepherd@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed