One of my first memories in the kitchen is from when I was two. Too tiny to reach the countertop, I’m standing on a step stool, hovering over the pizza dough that my dad has rolled across the counter. He’s spreading tomato sauce and I’m shoving handfuls of shredded mozzarella into my mouth. I’m not sure if I contributed anything to the final result other than my enthusiastic presence, but it’s the first time I can recall being a part of producing a meal from scratch.

I grew up in a house with two parents who cooked and baked and generally enjoyed spending time in the kitchen. For birthdays, we decorated cakes and adorned them with as many candles as possible, and for Valentine’s Day, we cut out heart-shaped cookies and dumped a probably unhealthy amount of sprinkles on top. One Thanksgiving, my dad made cranberry sorbet in the ice cream machine we had recently acquired, and we all oohed and ahhed over the result. But more than that, I remember my parents cooking together on a regular basis, listening to music while they stirred risotto on the stove, swaying in each other’s arms while their food baked in the oven.

Food has always been an integral part of my family. Throughout my childhood, every time my grandma came to visit from New York, she filled half her suitcase with boxes of brownies and lemon shortbread that she always made a show of unpacking for me and my brother, much to our unceasing delight. She never came empty-handed. My grandparents on the other side drove to our house every year to help my parents prepare for Passover, and every year my grandma, mom, and I peeled and grated apples to make charoset while my grandpa, dad, and brother rolled matzah balls and dropped them in boiling broth.

Our kitchen was rarely empty, and our house always carried the scent of whatever recipe my parents or grandparents were trying next.

Flash forward to the age of ten, and we’re eating frozen meals every night—often the same one for three or four days in a row. My dad died earlier in the year after an eleven-month illness, and any energy or passion for cooking my mom once had was gone. Feeding two children became a burden rather than a joy. I wish my brother and I knew enough then to stifle our complaints when we saw defrosted lasagna on our plates for what felt like the hundredth time.

For a while during my dad’s illness and then after his death, we had friends dropping off full meals on our doorstep several times a week. When the people around us felt helpless as they watched my dad deteriorate from the cancer spreading through his body—and then even more so as they watched us mourn—they cooked. They poured their care and compassion into the dishes they delivered to us. While I now largely associate casseroles and broccoli quiches with feeling like my family is falling apart, the older I’ve gotten, the more I can appreciate the love they tried to transmit through their food. But during that first grief-filled year, the sympathy meals slowly stopped and my mom became increasingly responsible for putting food on the table. Even now, I can still taste that defrosted Costco lasagna if I think about it too much, despite eleven years having passed since it made regular appearances on our plates as clumps of cheese and meat drowned in tomato sauce.

When I was in middle school, my mom got a new job that required her to commute into Cambridge by train. I started prepping meals per her instructions so that dinner would be ready when she got home. Throughout middle school and high school, I slowly learned to make pasta, rice, and chicken, in addition to mastering the skill of following the directions on pre-packed food (shoutout to Trader Joe’s).

Then, when I was in high school, my mom began printing recipes from Bon Appétit and The New York Times Cooking and leaving them on the counter. At first, they just built up into a stack of pristine white sheets of paper taking up valuable counter space, but eventually, she took the top one off the stack and bought the necessary ingredients. Over time, the print-outs became splattered in oil and covered in her pencil notes. I began staying in the kitchen while she cooked. At first, it was so we could listen to music together, but slowly I began chopping ingredients or running the mixer while she consulted her instructions. Her single pile of recipes became two, then four, and soon we were testing out new meals several times a week.

In the past few years, I’ve watched my mom regain her love of cooking. I’ve seen the determination in her smile every time she tries out a new recipe and the pride in her eyes when she serves it on the table. But when the pandemic hit and my brother and I were home all the time, meal prep began to feel like a burden again. Partly out of a desire to help and partly out of sheer boredom, I found myself wandering into the kitchen between Zoom classes in the endless empty hours that seemed to blend into each other.

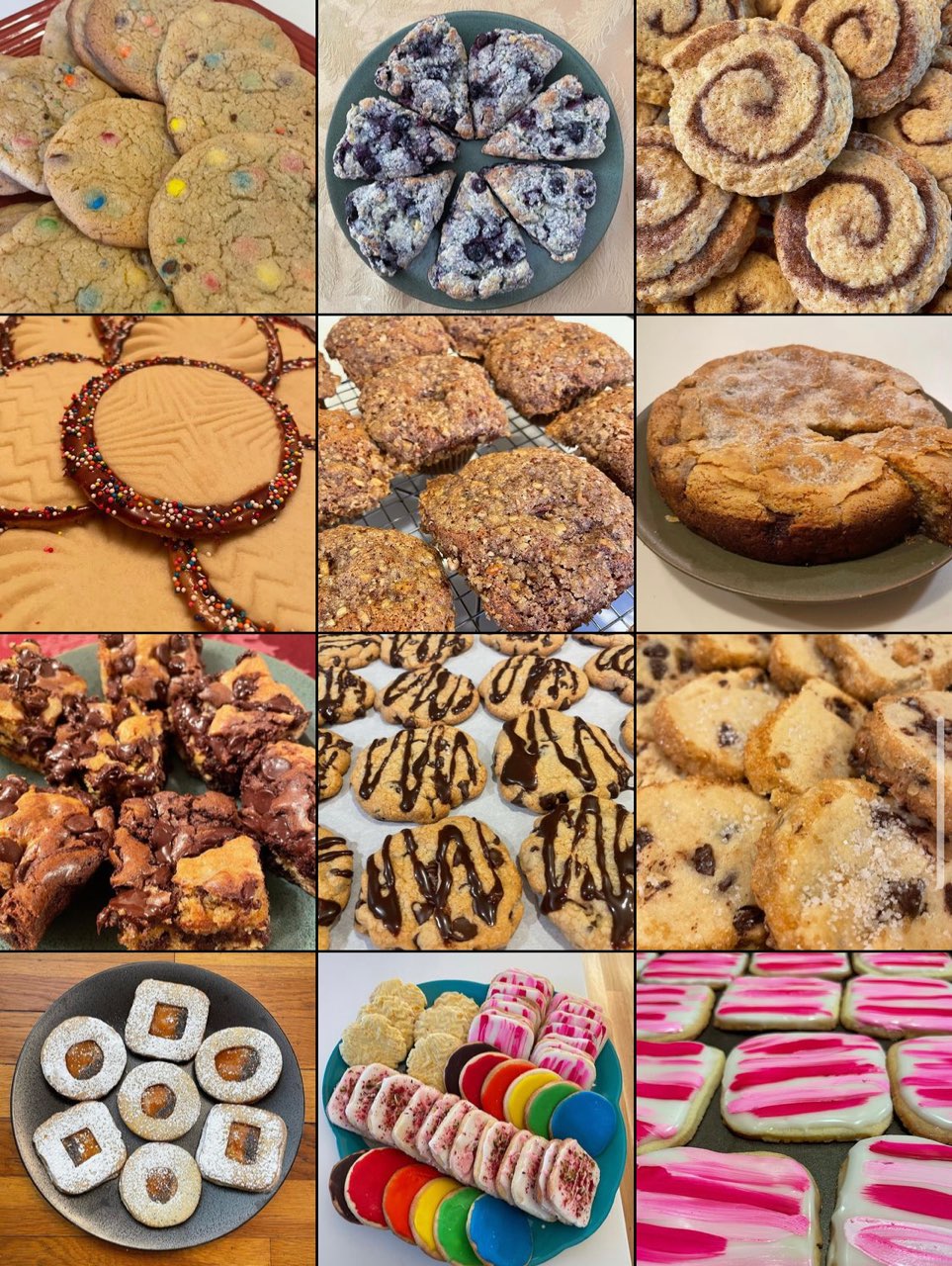

It started with chocolate chip cookies and my lifelong adoration of our KitchenAid standing mixer. One day early on in the pandemic, I could tell my mom was stressed by her remote work, and our house felt too still, too quiet. I took the mixer out of the cabinet and spent an hour rolling dough into balls and sliding parchment paper-covered trays in the oven. The whole house smelled of chocolate chip cookies by the time I had finished. If the warm aroma wafting throughout our home wasn’t enough to make the endeavor worth it, my mom’s grateful smile surely was. I could tell how much the cookies had cheered her up, so a few days later, I wandered back to the kitchen and tried a different cookie recipe. From then on, it was like I had tapped into my inner cookie monster. I could not stop baking. The process of mixing sugar, butter, flour, baking powder, and salt into dough became addictive. I loved watching the ingredients come together into something cohesive, and I loved the potential to use baking as an opportunity to create art.

Eventually, I moved from cookies, cakes, tarts, cupcakes, and crumbles to trying to cook more savory foods. I attempted eggs Benedict, tomato mozzarella pie, quiche, stir-fry, and so many other recipes that I can hardly keep track. I burned my arm on the inside of the oven (there’s still a scar!) and singed my hand on the stove-top burner, not to mention spilled ingredients on the floor more regularly than I’d like to admit.

The food I made eased the dreariness of staying at home and provided me with an outlet for my stress, my creativity, and my unquenchable thirst to learn—all while making a mess, of course. Mostly I baked and cooked to share with those I love. Leaving cakes or tarts on my friends’ doorsteps and mailing chocolate chip cookies to my great aunt in Philadelphia became a way to bridge social distancing and bring me a little closer to those I wished I could hug.

As the pandemic restrictions eased up, and I went off to college, I found myself returning to the kitchen for comfort whenever I needed it. When I’m stressed after a long day of classes, I chop vegetables and make risotto. When I notice a friend feels down, I pull out the red KitchenAid mixer my mom gifted me for my 21st birthday and whip up a batch of cookies. When I simply feel the urge to create, I scroll through The New York Times Cooking app and bookmark all the recipes I want to try, then I choose one at random and hope Weshop has all the ingredients.

Now, I bake wearing my dad’s old apron, and I think of my mom every time I turn on the oven.

Rachel Wachman can be reached at rwachman@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply