In 2012, after a bank foreclosed on her mother’s home, Heather Cassell ’23.5 found herself living at her best friend’s house. What at first may have felt like an extended sleepover soon came to an end when Cassell and her mother were suddenly asked to leave. With the small amount of money she had managed to save, Cassell’s mother purchased a fifth wheel—a type of trailer that can be attached to a truck. For the next seven years, the family moved from campground to campground across southwest San Diego, until Cassell was admitted to Wesleyan University, which promised food, WiFi, and a permanent roof over her head.

However, just one semester into Cassell’s undergraduate degree, COVID-19 swept its way across the world, forcing the University to close its doors. The lack of feasible housing alternatives left Cassell with no other option than to make a long journey back to the West Coast.

Once there, Cassell became tied to a cycle of couch surfing, spending months moving among family members, friends, and her 2009 Mazda 3. By the winter of 2020, the constant movement as well as the University’s insufficient attempts to provide stable housing had failed to provide the kind of life and healing process that Cassell, who had previously lived with an abusive father, needed.

“I am tired of doing this,” Cassell recalled saying to herself while driving around San Diego. “I will not live like this anymore. I have decided.”

It was around this time that Cassell stumbled across a series of tweets from fellow Wesleyan students and QuestBridge scholars Jess Burks ’23 and Mo Andres ’24. Not only were they, like Cassell, seeking stability as first-generation, low-income (FGLI) students, but they were also looking for someone to live with them in an off-campus apartment.

After a series of online exchanges, the group composed an email to Jennifer Wood, the Dean for the Class of 2023, and informed her of their intention to live off campus. She referred them to the Office of Residential Life (ResLife), which, on Monday, Feb. 1, 2021, rejected their petition for permission. This was the first of many such rejections.

The group decided to launch a campaign under the hashtag #reformResLife, calling upon the administration to acknowledge their extenuating circumstances and excuse them from the University’s requirement that students live on campus for all four years. Support for the three students intensified within the student body, as many other students began to reach out and share that they had faced similar challenges while navigating University housing.

Meanwhile, reports of inadequate and unreliable year-round housing, the administration’s adamant refusal to let students find independent housing solutions, breaches of privacy during the petition process, and even threats from University personnel made it clear that the University’s housing process was in need of drastic reform. In its current state, many felt that the system could not meet its students’ physical and psychological needs and did not provide the kind of long-term stability that students like Cassell, Burkes, and Andres desperately sought.

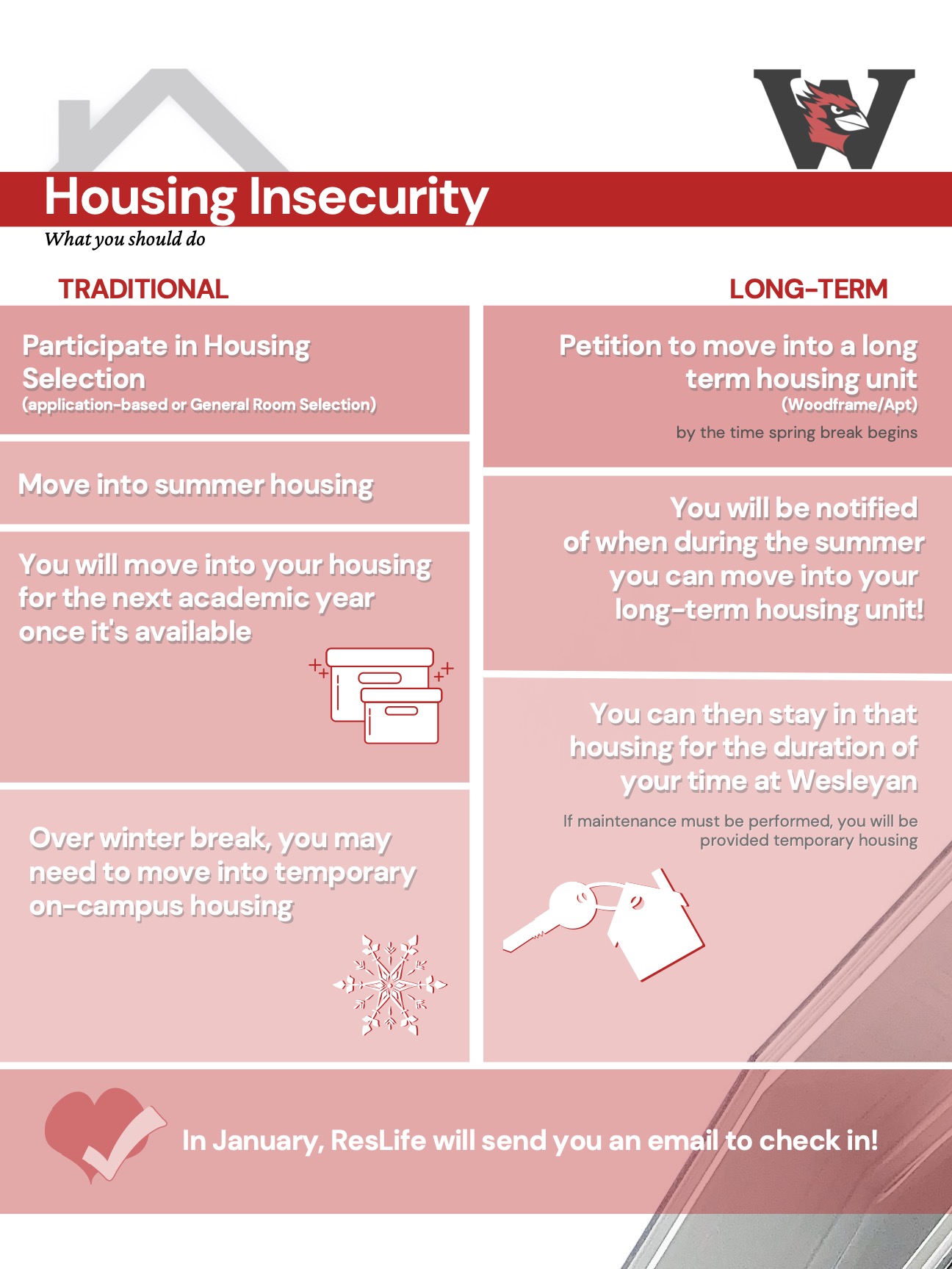

Now, almost two years later, Cassell’s and other impassioned students’ efforts have helped to radically transform the University’s housing policy. These changes include allowing housing-insecure students to receive year-round lodging; providing an option where students can petition to move into a long-term residence, such as an apartment or house, where they may remain throughout their time at Wesleyan; granting access to previously off-limits storage space in the attics and basement of long-term housing; and making it possible for students to live off campus based on their individual housing needs.

According to the Director of ResLife Maureen Isleib, the majority of these changes were developed in collaboration with students who have served in WSA leadership positions. Cassell, for example, was appointed as the most recent Chair of the WSA Equity and Inclusion Committee (EIC).

“The Office of Residential Life worked closely with WSA leadership to codify the different housing options available to students experiencing housing insecurity,” Isleib wrote in an email to the Argus. “The WSA leadership has been very helpful in getting the word out to students, and we’ve noticed more students who are being proactive in trying to secure break housing well in advance.”

In addition to improving its housing policies, the University has sought to modify the way it tackles issues regarding housing insecurity.

“We have identified the class dean as the point person for a student experiencing housing insecurity,” Dean Patey wrote in an email to The Argus. “The student can reach out to the dean to share information, and the deans will collectively consider each request. When a student has been determined to be housing insecure, they do not need to go through the process with any other office. The goal of the dean serving as a point person is to ensure that the student does not need to share their story with multiple people on campus in order to get their needs met.”

The University hopes to establish this individualized approach from the beginning of a student’s time at Wesleyan.

“The process starts with first-year students, who are asked on their preference forms if they anticipate needing housing over the break periods,” Isleib wrote.“Of course, students’ circumstances change, and they can reach out to their class deans at any time, not just [in] their first year. When a student is identified as having housing insecurity, the class dean will make a note on that student’s record, and they are directed to indicate that they have circumstances that prevent them from leaving campus on their break housing application.”

ResLife’s new policies and practices are the result of continuous interaction between students and the administration. These channels of dialogue have helped ensure that changes to the housing policy are effective and reflect students’ needs. For example, the University has deliberately refrained from creating a single, narrow definition of housing insecurity. This gives administrators discretionary power to dictate who is housing insecure without excluding certain students.

“The University recognizes that housing insecurity exists…and that it’s nuanced,” Cassell said, “And that [students’] needs may change over time.”

For Cassell, engaging with the University through her role on the WSA has been eye-opening.

“After working with these people for a while, they are just people,” Cassell said. “We are all genuinely on the same team. It’s not a fight, it’s a ‘hey this is the problem and you and I are working together, you and I, as in student body and administration, to solve it.’”

However, many challenges remain for students seeking to secure stable, and—in Cassell’s words—dignified housing.

“There’s no real centralized system of communication [in the housing process] at all,” Cassell said. “There’s just such a splintering of communication paths.”

Housing petitions and requests are often time-sensitive and therefore require prompt responses. This is particularly important for international students, who may need to move into their housing unit early or remain in their residence during break periods due to changes in flights or travel guidance.

In addition to these problems, Wesleyan’s four-year residential campus raises questions about how adult college students, seeking greater independence and freedom, are supposed to live and interact with an institution that controls almost all aspects of their lives. In other words, because the University has more or less unrestrained access to students’ homes, and the power to establish its own set of rules, how much autonomy do students actually have?

“Being a student on a campus means that you’re being surveilled,” Cassell said. “Constantly having my house checked for things that are legal by any other standards, but are illegal on a campus, and not being able to just work with one person who is going to be working on my house, is not fun. There are a million different outside contractors.”

ResLife says that it is working with the Facilities staff on space and policy issues that may impact its students. It is imperative that the University strives to provide housing that is appropriate for each individual and leaves students feeling safe and respected. As the world begins to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, so too do the students of Wesleyan, many of whom have turned to the University for increased support and assistance, especially where housing is concerned.

“[Housing insecurity] has been growing over the past few years, and COVID created a number of situations in which students were unable to secure housing away from campus during the break periods,” Isleib wrote.

Currently, 75 students have been identified by the University as housing insecure. This past summer, 30 students submitted petitions to ResLife based on individual needs and were granted authorization to move back to campus early without penalty.

Previously, those who arrived on campus without the University’s permission were issued a monetary fine. In an effort to remove the financial inequities this created, ResLife, in conjunction with the Community Standards Board, altered this policy and instead began issuing one disciplinary point per day that a student moved in early. According to Isleib, eight students were given points for moving in early. Of these students, three reportedly came to campus despite being told they could not move in early; the other five arrived on campus without communicating with the University beforehand.

ResLife said that all students who met the criteria were granted permission and therefore did not receive judicial points. Nevertheless, issuing points for early arrival remains contentious and may exacerbate existing problems.

“[The University doesn’t] see that if you have an exorbitant number of points, then you are more in danger of not being at Wesleyan,” Cassell said. “Therefore your entire future and your immediate housing is jeopardized.”

While grateful for the progress made thus far, Cassell remains acutely aware that the University’s housing policy as well as its treatment of those who improve and sustain residential life on campus are by no means perfect. Recently, Cassell decided to resign from her position on the WSA.

“I joined the WSA so that I could continue to do the work I was doing with a bit of credibility and money,” Cassell said. “I wanted to get paid for the intellectual and emotional labor that I was doing in changing policy. And if you are on work-study, you receive a stipend for being on the WSA.”

For Cassell, however, this stipend did not reflect the amount of time and effort that she had dedicated to her role on the EIC.

“I have still been constantly thinking about housing because it is just like ‘Okay, then what am I doing next semester?’” Cassell said. “And I wanna focus on school so badly. I love school. It’s how I got here.”

It’s about more than just balancing time. For the past two years, Cassell has spent countless hours negotiating and reforming complicated policies, almost all of which has been entirely unpaid.

“At the moment, [the stipend is] only like $300,” Cassell said.“During the reform, I got paid nothing.”

After leaving the WSA, Cassell expressed that she hopes to find fulfillment in other projects.

“Now I can go, ‘Okay I can give my energy to something that actually gives it back to me, something that I derive joy from and something that will pay me, quite frankly,” Cassell said. “Because, especially when you are in a leadership position on the WSA, it becomes a lot more work.”

Cassell is not alone in her frustration. Several student groups and individuals have pushed for the University to better acknowledge and compensate them for their contributions to campus. On Sunday, Dec. 4, the Wesleyan Union of Student Employees, which represents close to 100 Resident Advisors (RAs), Community Advisors (CAs), and House Managers (HMs), held a rally on the steps of North College. The union sought to drum up support for more equitable compensation and greater recognition for the University’s student employees.

Cassell is now stepping back from her duties on the WSA with the knowledge that her efforts have provided an invaluable framework for others to enact change. She hopes that the University not only adapts to meet the housing needs of all its students but also recognizes the hard work of those who keep ResLife going day in and day out.

“The reason why they put me through everything that they put me through is because they were holding fast to this label of [being] a residential university,” Cassell said. “If they want to hold onto that so tightly, they need to make good on that promise and house their housing-insecure students in the least stressful way possible. And they need to pay people who make it a residential institution because the only reason why this is a residential college is because of the RAs, and the HMs, and the CAs.”

Tiah Shepherd can be reached at tshepherd@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply