I’ve found that semi-autobiographical works tend to be pretty hit or miss for me. That’s not to say that the genre hasn’t produced films I like; Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari” and Lulu Wang’s “The Farewell” are some of my favorite movies of all time, and both are semi-autobiographical works. Steven Spielberg’s latest film, “The Fabelmans,” is also a hit for me, personally.

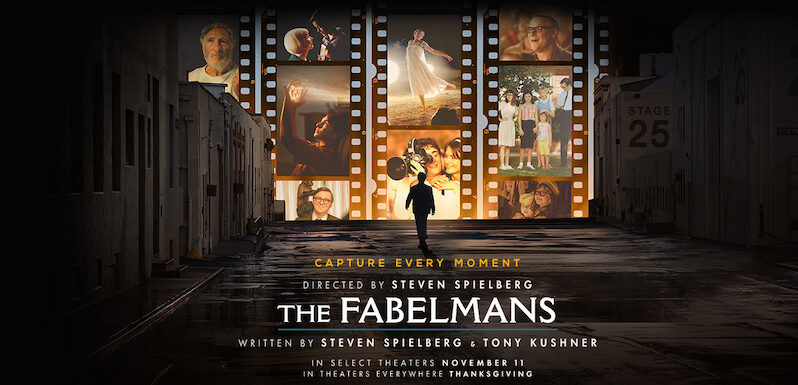

I was lucky enough to catch this movie at the Film Series’ Super Secret Special Screening on Nov. 11, but I also went back to rewatch it with a small group of friends once it premiered in theaters on Thanksgiving. After quite a few recent misses—2021’s “West Side Story” and 2019’s “Ready Player One” come to mind—Spielberg manages to create something fairly fresh and new with “The Fabelmans,” all while drawing from an all-too-familiar source: his family.

This movie follows a young, aspiring filmmaker, Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle), through most of his childhood up until young adulthood, with Spielberg drawing heavily from his own life. Spielberg invites viewers into his family home and his family dynamics as he takes us through Sammy’s journey as a filmmaker. It’s a fairly simple premise, but Spielberg does it well. There are strong dramatic throughlines in “The Fabelmans,” both as Sammy learns to walk the line between his love for his craft and his love for his family and as tension grows between his parents, Mitzi (Michelle Williams) and Burt (Paul Dano). Both collide in the very last scene of “The Fabelmans,” which perhaps best shows Spielberg’s (and Sammy’s) complex feelings on family, filmmaking, and love.

There’s an intense negotiation at the heart of “The Fabelmans”: the tension between seeing and being seen, and between portraying and being portrayed. Spielberg fashions a deliberate distance between Sammy and those in his life, and LaBelle’s performance helps drive home the question Spielberg asks his audience: how can you dedicate yourself wholly to capturing the little nuances and moments of life, when doing so requires you to always be separated from them? Perhaps even more central to the drama unfolding within the Fabelman family: how do you reckon with the incredible selfishness it takes to dedicate yourself wholly and completely to a craft, when you know it means everything else will come second to it?

Spielberg gives us a handful of different answers to those questions in the shape of Mitzi, Burt, and Sammy himself. Williams gives a show-stealing performance as Mitzi, Sammy’s ephemeral mother. She’s a waifish, ditzy sort of character, who we learn has set aside her artistic passion—the piano—in favor of family. But that sacrifice is killing her; much of “The Fabelmans” follows Mitzi’s slow, steady decline over the years. She’s increasingly miserable in her marriage, unhappy with her life, and in love with her husband’s best friend, Benny (Seth Rogen). Mitzi is one half of a warning sign—a sign of what could happen to Sammy if he does what his father wants and gives up on filmmaking entirely. Mitzi is a ghost in her own home, floating and slowly fading away, even as she steals the camera’s attention every single time she steps in front of it.

In contrast to Mitzi, Spielberg gives us Burt, Sammy’s emotionally distant father. He is a computer genius whose first priority is work, as shown by the way he continually uproots his family as he moves up in the world, from New Jersey to Arizona to Silicon Valley. We’ve seen Burt’s archetype before in plenty of Spielberg movies, but Dano brings a humanity to Burt that sets him apart in a long canon of Spielberg father figures. Burt is the other extreme answer to Spielberg’s questions about balance, craft, and dedication. He’s dedicated himself wholly and completely to doing what he loves: engineering computers. But this has been at the cost of his interpersonal relationships. He loves his wife, but his marriage is failing. He leaves his so-called best friend Benny behind in search of better opportunities. He and Sammy seem to be constantly at odds with one another, as Burt tries to push Sammy into leaving his dreams of filmmaking behind for a more stable career path. But, and this is a big but, at least Burt is doing what he loves.

Sammy, then, is probably meant to be a middle ground; able to do what he loves, while keeping the people he loves in his life. But Spielberg shies away from this easy, pithy Hollywood-style solution. Rather, Spielberg doubles down on the competing ideals of selfishness and sacrifice. In what might be the most memorable scene in “The Fabelmans,” featuring Judd Hirsh as Sammy’s great-uncle Boris, Spielberg lays down a truth: to love your art, to dedicate yourself to it, is the ultimate selfishness. There’s no such thing as a happy medium. Your art will come first, and everything else—yes, even the people you love—will be second.

But despite that truth at the center of “The Fabelmans,” it remains a fun movie. There’s heart to it, helped immensely by the cast’s brilliant performances (with Dano’s and Williams’ performances being the absolute standouts for me), and the fact is, at the end of the day, “The Fabelmans” is undoubtedly Spielberg’s love letter to the art of moviemaking. Every little shot, every scene, every moment in this movie is dedicated to the art of it all, and I think that’s probably what I appreciate the most about it. It’s hard to hate a movie that’s so honest about what it loves, and I think this might be my favorite Spielberg movie yet.

Nicole Lee can be reached at nlee@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply