As fall turns to winter, leaves in myriad colors migrate from the heights of their display cases to the earth below, leaving behind bare limbs reaching to the sky. It is becoming the season of sticks, a bleak and desolate time in New England that I have been, funnily enough, looking forward to for months—not because I love the cold, but because I love a song.

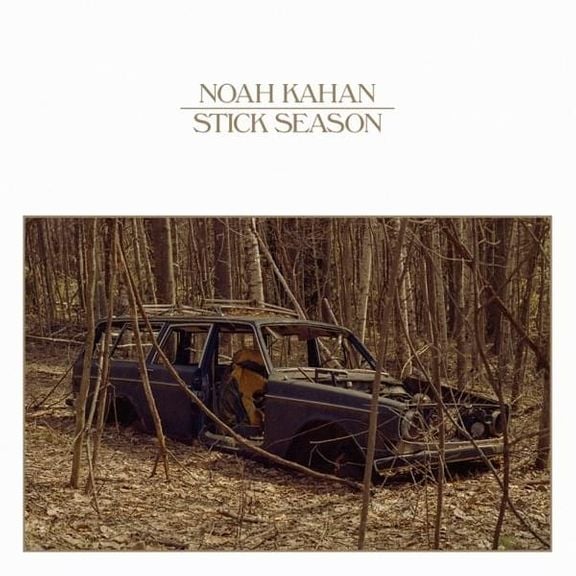

Singer-songwriter Noah Kahan released his single “Stick Season” this July and somehow got an entire friend group of Californian boys sweltering away in un-air-conditioned living rooms hooked on a desperate folk song about November in New England. Knowing that I would actually be experiencing a stick season of my own, I patiently waited for the leaves to fall and the landscape to become as bleak as Kahan’s sentiments. And on Oct. 14, just before the landscape transformed, Kahan gave his single companionship in the form of his third full-length LP, also titled Stick Season.

Kahan’s most vulnerable record yet, this masterpiece marks a shift away from Kahan’s previous indie-rock heavy sound, diving deep into the world of acoustic folk music. A strong awareness of place and time carries the album forward and carries listeners with it into Kahan’s New England. And for us lucky listeners who already reside in this world, Stick Season provides a perfect soundtrack to our remote lives on the eastern seaboard. So let’s take a track-by-track look at the stories it tells.

“Northern Attitude”

The muted pickings that open this track are deceitful. Beginning as a deceptively quiet ballad, this cinematic masterwork blooms into one of the most raucous and booming choruses of the album. Kahan asserts his New Englander identity firmly from the first verse of this first track, ushering readers into the setting that will be the backbone of the rest of the album. The lyrics are bleak and honest, lamenting the caution with which the broken-hearted enter new relationships and the ease with which they slip away. Kahan is profusely apologetic, even self-deprecating at times; he will remain this way for most of his album. Poetic, personal, and ripe with details and anecdotes, this track introduces us to Kahan’s poetic style with a narrative slightly less emotionally taxing than many of the others on the record.

“Stick Season”

In many ways, this is the album’s thesis. Not only did it introduce many listeners to Kahan and his new style and entice them to hear the rest of his tales, its heartbreaking lyrics and firm sense of time and place drive the rest of the record. Though considerably quieter than the previous song, “Stick Season” has an unrelenting pulse that pushes it forward where its predecessor stagnated. Lyrically, we see Kahan lament a loss—of a person, or perhaps a place or moment in time—in one of his most self-aware performances of the album. He seems to understand the desire to victimize himself that he expresses throughout and sees how the world and its inhabitants can easily move past his stagnant, old-timey self. If we are looking at this album as a single story, as perhaps we should, this seems to be the context or the aftermath of the opener; either the loss that prompted its self-deprecating wallowing or a moment of reflection some days after the initial pains of separation have taken root.

“All My Love”

Though Kahan may not really know how to be happy without strings attached, we see him in a more optimistic and hopeful avatar here. The folksy, bluegrass-inspired gem is one of my personal favorites; its use of dynamic contrasts between the verses and choruses is reminiscent of classic Americana and seems to hit the listener with sharp turns whenever they begin to feel comfortable coasting along. Of course, this track also deals with loss, but it is more so as a celebration of what once was and what still remains, and less of a lament of all that is gone.

“She Calls Me Back”

This pop-infused track is the album’s emotional high point; we see Kahan crossing into somewhat happy territory! A bit of a break from the folk-heavy sounds of the rest of the album, this song stands out in its style, but not its tempo—it remains at roughly the same pace as its three predecessors. It also tends to resolve in a major key—true of every song on the album, more or less. The use of similar tempos to start the album creates a sense of cohesion that binds these first four tracks together, perhaps to group them as a single narrative or to drive the album’s opening forward with a collection of uncharacteristically fast-paced works.

“Come Over”

The album’s first waltz, this ballad marks a clear shift from the first four songs. It is both significantly slower and much quieter, giving listeners a moment to breathe and soak in Kahan’s lyricism. Status becomes central to his self-ridicule, and he places himself at the bottom rungs of his town’s hierarchy. He continues to lament the loss of a loved one, and is as self-deprecating as ever here, but he begins to introduce metaphors of place into the equation. We are left with gems such as, “And my house was designed to kinda look like it’s crying / The eyes are the windows, the garage is the mouth / So when they mention the sad kid in a sad house on Balch street / You won’t have to guess who they’re speaking about.” On the surface, Kahan likens himself to his house, but the personification of the house here raises questions of who Kahan lost and what he is lamenting—a lover, or a home or a sense of place.

“New Perspective”

This is one of the moments where Kahan gets closest to performing in a minor key; the resolutions on this track tend to jump from major to minor, giving it a certain uneasy instability that leaves listeners unsure where the melody may travel next. Place is once again personified; this time, rather than a house, it is a town. Kahan’s mourning of the changing nature of his hometown leaves listeners with a new idea—that the supposed lover that was the subject of the preceding five songs is actually his town, not a person. Echoing the tensions between the resolutions on this track, Kahan introduces thematic tension between his desire for his memories to be preserved and the modernization of the place he writes about. This tension alludes to the conflict between stagnation and forward motion that appears in the first three tracks; Kahan continues to stay in place while things whizz by.

“Everywhere, Everything”

This second waltz features some of the most beautiful crescendos of the album. Beginning just as quiet as the last, its choruses are accompanied by meteoric rises in energy and volume. Cymbals crash as Kahan croons over the swirling major chords of the sonic landscape. A rare moment of happiness, this song is simply a love song, with very few strings attached. Though Kahan leaves it ambiguous whether his love is reciprocated, the lack of self-deprecating comments and hopeless metaphors is welcome.

“Orange Juice”

This intensely cinematic composition is probably my favorite on the album. The use of two tempos and a clearly delineated slower intro is reminiscent of many jazz and classical compositions—an almost obsolete technique in today’s pop. This song, just like the album’s opener, builds from a quiet lament to a rousing, symphonic story. This vignette is told from two perspectives, adding character and depth to Kahan’s poetics. Recurring themes of staticity, time, place, and change remain, but this time in the context of a story about a friend’s alcoholism and subsequent sobriety. This break from material solely about love and loss gives Kahan’s collection—and the listener’s ideas of his town and world—new depth; we are beginning to know more about his town and its inhabitants.

“Strawberry Wine”

Once again we are met with the joy of a song in two tempos, this time with an even more unorthodox structure. The chorus of this song, if you could even call it that, never repeats. Kahan gives us a poem, free-flowing and without refrain. The seemingly incomplete nature of the song mirrors the incomplete feeling Kahan is left with as he ponders the loss of the relationship he laments throughout this song. This necessary change of pace comes at a perfect time and shows Kahan’s mastery of a listener’s cravings. Speaking of cravings, what is strawberry wine? Sounds yummy.

“Growing Sideways”

Upon first listen, it was hard to tell if this was a new song or not; the deliberate choice to have back-to-back songs in the same key with similar instrumentation provides listeners with satisfying continuity. These are some of Kahan’s most utterly devastating lyrics, including (but not limited to) “But I ignore things, and I move sideways / Until I forget what I felt in the first place,” and “Oh, if my engine works perfect on empty / I guess I’ll drive.” Noah, I hope you are doing ok.

“Halloween”

This third and final waltz shows changes in Kahan, finally ready to move on. As he writes about leaving his home, we see glimmers of growth—a new willingness to move with the times and an ability to move past heartbreak and make a life for himself. The self-deprecation is replaced with new confidence. While I am happy for Kahan and this growth, I am left longing for some of the heartbreaking details of the rest of the album.

“Homesick”

This alt-rock anthem is perhaps the most similar track on this LP to Kahan’s previous work. Unorthodox structure rules again, this time with a clearly defined chorus that repeats twice, back-to-back. The double meaning and conflicting nature of ideas surrounding being “homesick” here is worth dissecting; though ideas of homesickness usually allude to a desire to be at a home one is far from, in this instance Kahan is literally just ill with grief at home. And yet the title alludes to a desire to be at home and remain in that home, and “die in that house that I grew up in.”

“Still”

I am not the biggest fan of this song.

“The View Between Villages”

One of the album’s sparsest moments, this final vignette sees Kahan finally at peace. He is neither here nor there, but he is at peace with his liminal status. In transition, from one place to another, from one love to another, from heartbreak to acceptance, he finds stillness and solace. Meditative, structureless, and ambient, the track is a satisfying conclusion to this masterpiece of an album.

Ahkil Joondeph can be reached at ajoondeph@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply