c/o Everybody Instagram

To summarize the plot of the fall semester department show in two words: Everybody dies!

To offer more nuance: “Everybody” by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is a show that explores the themes of death, love, and interpersonal relationships through an unconventional and format-breaking approach. Five people—Isabelle Chirls ’23, Evan Sullivan ’23, Mo Andres ’24, Max O’Hare ’23, and Skye Figueroa ’26—play Somebodies. These Somebodies roll the dice each night (literally) to determine the roles they will play, underscoring the randomness of death. As the Usher (played by Michayla Robertson-Pine ’22.5) tells the audience, each show has a totally random assortment of roles, and actors will not always play people: if they are not Everybody, the Somebodies will roll Friendship, Cousin, Kinship, or Stuff, roles that reflect ideas than personalities or named characters.

The plot of the show is difficult to summarize quickly, but I’ll offer context so my commentary can make as much sense as possible (which might be difficult when I’m talking about characters such as Stuff, which is literally all of the material wealth Everybody has accumulated over the course of their life).

The Usher introduces the audience to the show before seizing on-stage and being possessed by “God,” a seamless if unsettling transition from pre-show ritual to show that is the first indication that this show does not want to conform to the boundaries of traditional theater.

And no, I’m not putting “God” in quotation marks to be cheeky; Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, the author of the show, wrote the role this way. “God” asks Death (played by Luciel Sanchez ’24) to bring Everybody ASAP and give “God” a sense of why they lived their life the way they did in order to understand the imperfect experiment that is humanity.

Death then finds the five Somebodies, who have been sitting in the audience up till now. After realizing that they are going to die, the Somebodies beg Death to allow them to find someone to take with them to “God” to help with their presentation about their life. Death reluctantly agrees before the Usher returns to facilitate the rolling of the dice.

I had the pleasure of watching all four official performances of “Everybody,” which ran from Nov. 10 to Nov. 12, so I saw four of the five main actors play Everybody. I also saw them rotate through the other chance roles, which gave this show incredible re-watch potential. Every time was a brand new experience and a brand new story for me to watch.

The nature of the show, where the five Somebodies have to memorize the entirety of the script and many roles are double-cast (the Somebody who plays Kinship later on in the evening performs as the Five Senses, one of Everybody’s virtues), gives actors an excellent playground to show off their range of skills.

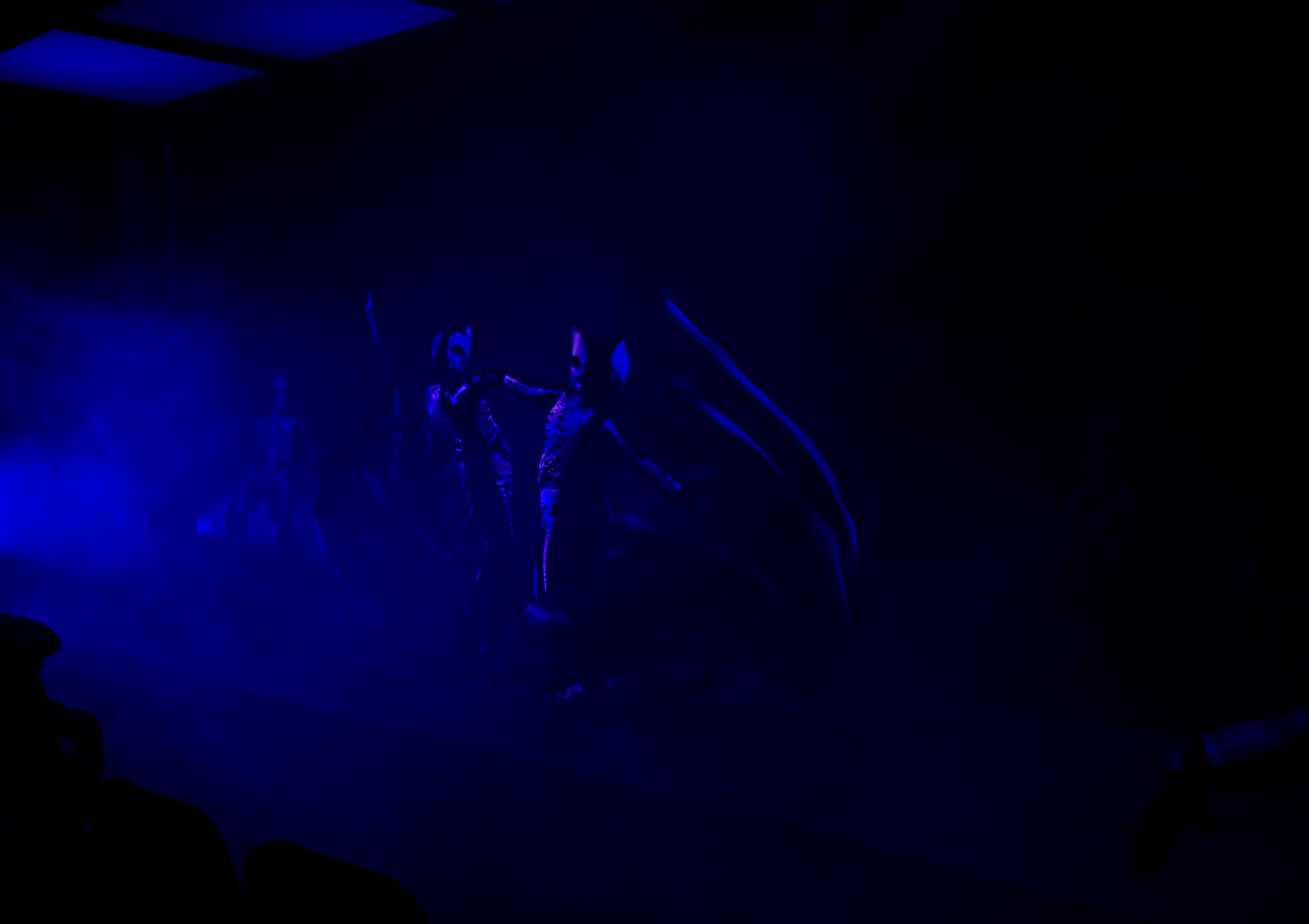

c/o Sam Harris

“Everybody” is a fever dream of a play. Its narrative is predominantly monologues during which abstract concepts speak to Everybody during their dreams that are interrupted occasionally with commentary from voices that are only heard, not seen. Its dream-like quality is enhanced by the watery lighting (designed by Sam Harris ’23) and clever use of sound design, making an audience feel just as submerged in the bizarre dream. Everybody is experiencing the end of their life as they are.

After begging Friendship in one scene, Kinship and Cousin (their cousin) in another (during which Kinship attempts to steal a Little Girl played by Chiara Naomi Kaufman ’24 from the audience so she can die with Everybody), and Stuff in a third to come help deliver their presentation to “God” and getting rejected each time, Everybody becomes desperate. Representations of their friends, family, and material wealth have been denied to accompany them on a journey to the afterlife, and they begin to fear that their lives were spent in pursuit of meaningless connections with others and their possessions. This is where the play’s traditional format breaks further: an audience member stands up and starts to leave the performance before confronting Everybody and telling them that he’s not happy with how he’s represented.

It’s Love (played by Marcos Arjona ’26). Love demands that Everybody humiliates themselves by taking their clothes off and running around while screaming about how they’ve been disappointing to themselves because they hate that their body is changing and that they cannot control it. During some performances, people started laughing. I felt dawning horror each time I watched this climatic scene. It hurt to watch Everybody come to terms with existentialism every time, even though it meant they were coming to terms with the eventuality of their death.

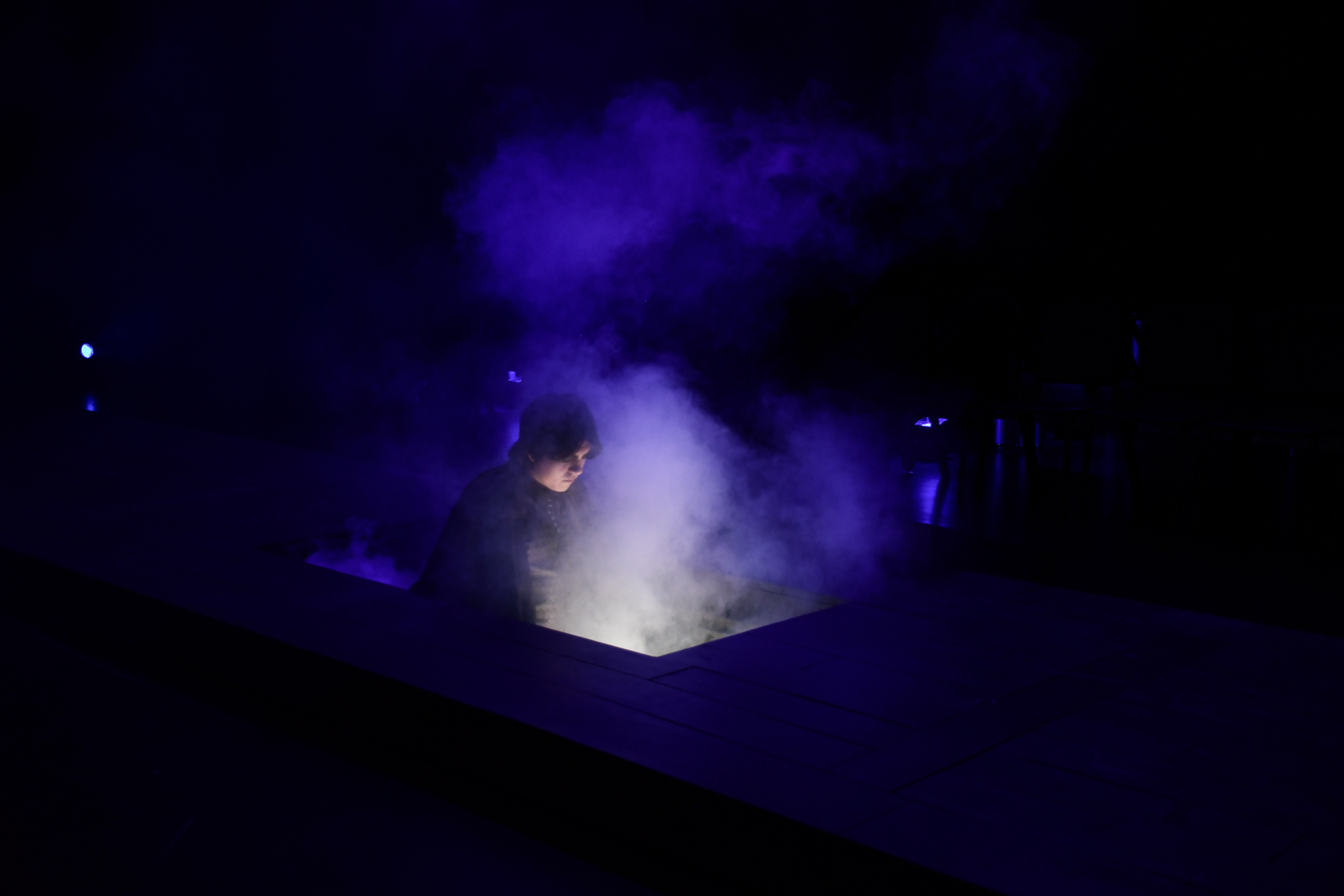

c/o Sam Harris

The usage of the space and the writing’s constant acknowledgment of the medium of the play makes “Everybody” feel electrifying. The actors know how to make you laugh and they know how to make you feel like your lungs collapsed, and they can transition from hilarity to tragedy in a split second. In some moments, you’re too busy laughing to remember that Everybody is in the process of dying.

After the humiliation, Love agrees to die with Everybody, and skeletons take to the stage to dance. At each performance, I found myself baffled by this section. I know it stays in line with the rapid flips from comedy to drama and back again, but I found myself wishing that the show’s interpretation of the dance had stuck closer to the original text of the script, which reads simply “Skeletons dance macabre in a landscape of pure light and sound.” It was a favorite for the audience as evidenced by their uproarious laughter, but I would have preferred if they had chosen to sustain the heavy moment between Love and Everybody through a more somber dance.

Death returns, perplexed by the fact that Everybody has found someone to die with. The Usher returns as Understanding and brings with them their crew of Everybody’s virtues: Strength, Mind, Five Senses, and Beauty. These virtues initially agree to come with Everybody to present to “God,” but change their minds when they realize what that actually entails. As each virtue departs Everybody’s side, they lose that aspect of themselves: first, their looks fade when Beauty runs off, then their body goes when Strength fails, then their Mind, and finally their Senses, leaving them blind.

c/o Sam Harris

Just as they start to enter the grave that leads below the stage and is belching fog, Evil (played by Miranda Derossi ’23, who was also a Somebody swing) runs into the theater and grabs Everybody’s hand to tell them that all the “shitty evil things you did” will be dying with them, too. The group of four departs into the grave, with only Death returning to discuss wrapping things up with Time (played by the same actor as the Little Girl) and Understanding.

At the end of the show, Understanding morphs back into the Usher, who reminds us that this, after all, is a morality play, and to take away a moral. Perhaps be better about recycling, they tell us. And be nicer to (drumroll please) Everybody.

Speaking of being nicer to Everybody, here are my thoughts on everybody’s Everybody:

While I couldn’t see Chirls’ Everybody, I did have the opportunity to see her as each of the concepts. She offered a grounding presence to those around her while boasting her capacity for impressive variability in her acting. Her range was evident from her fluid transformation within and between shows. Everything from her posture to her minute facial expressions changed when she shifted from role to role, and her choices were unique and bold.

The first Everybody I saw was Sullivan’s, and they say you can never forget your first. Sullivan blew me away with the narrative arc he drew with his steady speech and strong positioning on stage. He had the audience in stitches up until it dawned on us that he really, truly was about to die. As his Understanding left him, he sobbed, and it was a noise that ripped through me. I don’t think I’ll forget the feeling that settled into my chest when I left the theater.

Andres’ Everybody held that sad energy throughout their performance, which felt like such an interesting parallel following the hilarity of Sullivan’s from the night before. It felt like the fact that they were dying and the existentialist nature of the play never totally left their facial features, even during the comedic peaks of the show. Their death felt like the culmination of a tragedy you could see coming for a long time, but that didn’t make it hurt any less.

The Sunday matinee had the most boisterous audience, and their enthusiasm was paired excellently with the high-strung Everybody that O’Hare presented. O’Hare’s anxious Everybody kept the energy level high throughout the show. While it was made clear that all of the Everybodies were afraid of the fate that awaited them, O’Hare’s was genuinely terrified throughout the show with the dawning realization that they would die alone. Audience members had tears in their eyes at the crux of the show, when O’Hare’s Everybody collapsed after Love’s brutal humiliation and finally came to terms with the lonely fate that awaited them.

Closing night offered Figueroa’s Everybody, who was desperate and funny and deeply tragic at all the right moments. I had to double-check that Figueroa was a first-year with how comfortably she owned the stage as Everybody. This Everybody was just as lonely as they were ridiculous, which heightened the tension between the comedic and dramatic themes of the show in a way that was supremely rewarding to an audience member.

The personal touches and the love that these actors put into the show and into their characters were evident from what a joy it was to watch four times over. My biggest regret is that I can’t watch each and every possible combination (of which there are 120). To wrap this review up simply: Everybody in “Everybody” was exceptional.

Cameron Bonnevie can be reached at cbonnevie@wesleyan.edu.