Homecoming weekend is an opportunity for alumni to return to the University, reconnect with old friends, and reminisce about their college days. For Kyle Shin ’20, a San Francisco-based rapper who performs under the name Son of Paper, it was a chance to reflect and engage with two of the intertwined identities that shaped his time at Wesleyan: his identity as an Asian American, and his identity as a musician and performer.

Asian American History and Community with AASC

Shin’s weekend commenced with the weekly meeting of the Asian American Student Collective (AASC) meeting at 5 p.m. on Friday, Nov. 4. Shin was deeply involved with AASC during his time at the University, having served as the club’s co-chair and helping to originate its current organizational structure. He also noted the key role AASC had in connecting him to the University’s Asian American community, and his pleasure in seeing it continue.

“[AASC is] crucial for a lot of Asian and Asian American students, to help them understand what identity means to them on a college campus,” Shin said.

That meeting, held in room 110 of the Usdan University Center, featured three Asian American alumni: Former Board of Trustees member Tom Wu ’72 P’25, AARP Vice President of Diversity Equity & Inclusion, Asian American & Pacific Islander Audience Strategy Daphne Kwok ’84, and Shin. The three discussed their time at the University and how the experience of being Asian on this campus has changed.

Shin discussed his pride in the persistence of AASC and extolled attendees to stay in touch with the people they meet there.

“This is a vast network that will greatly help you in ways you can’t even imagine right now,” Shin said.

Kwok spoke about her work in politics and civil rights organizing, as well as her current role working in Asian American outreach for the AARP, and with the University’s Asian Pacific American Alumni Network.

“I use [my] position to advance Asian American students, faculty, and alumni,” Kwok said.

Wu revealed that he was the only Asian student in his graduating class at the University.

“Wesleyan was very different 50 years ago,” Wu said. “There wasn’t really a sense of Asian community. There were maybe five of us across four years.”

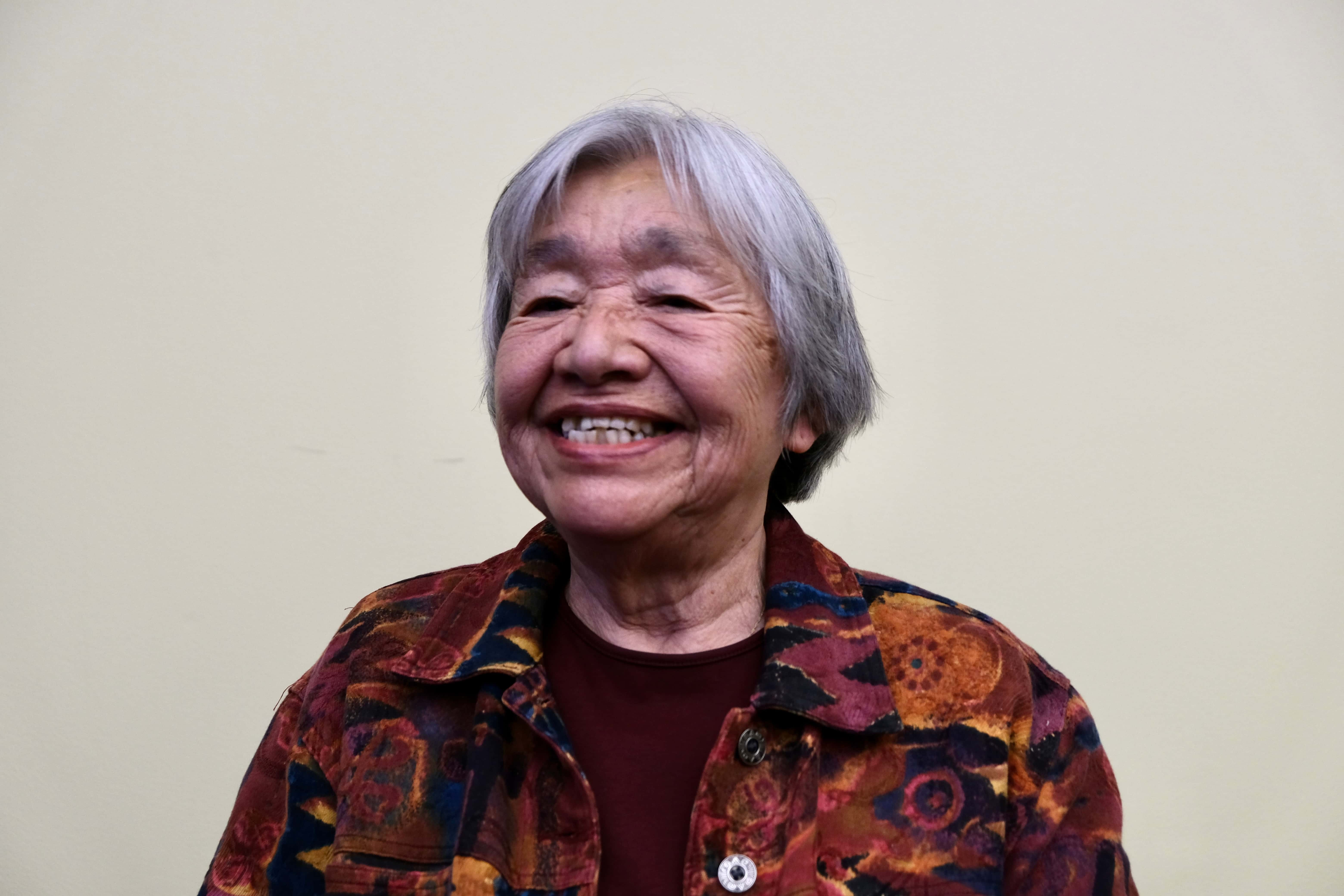

Also joining the discussion was Professor Emerita of Asian Languages and Literatures, Yoshiko Yokoichi Samuel, who joined the faculty in 1979 and went on to become the University’s first Asian tenured professor.

“One of the reasons I began teaching here was the Asian American students,” Samuel said, explaining that the first night she arrived, a group of Asian American students prepared her dinner. “They really helped me feel at home, to feel that I’m welcome and will have a place on this campus.”

Samuel also discussed the Boon Tan phenomenon. A campus joke from the 1970s, Boon Tan was allegedly the name of a Malaysian student who never arrived on campus, though his name-tagged luggage did. The mystery of Tan’s whereabouts turned him into a mythic figure on campus, with students making jokes about the absurd situations in which they claimed to have encountered Tan.

However, this fad also had an ugly, racist side: students tagged “the Boon Tan face” across campus, a slant-eyed smiley face image based on anti-Asian caricatures. Samuel described feeling shocked and threatened to see a Boon Tan face on the chalkboard on her first day of teaching at the University, understanding it as a racist taunt. She then became outspoken about the racist nature of the “joke,” despite defenses from non-Asian students who characterized it as a beloved campus tradition, including, Samuel said, the then-Editor-in-Chief of The Argus.

Exploring Self-Expression at CEAS

The first of three events Shin appeared at on Saturday, Nov. 5 was the 11 a.m. homecoming event at the College of East Asian Studies (CEAS). With attendees seated in the wood-paneled lecture hall in the Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies, Associate Professor of East Asian Studies and CEAS Chair Takeshi Watanabe introduced Shin and the K-pop Dance Crew (KDC) who kicked off the event, performing the routines of several K-pop hits.

Following KDC’s performance, Shin spoke briefly about his experience as a CEAS major. Shin traces his ancestry to two East Asian cultures, his mother a fourth generation Chinese American, his father a second generation Korean American. Growing up in San Francisco, Shin said, he often felt closer to Chinese culture, but at the University, he also got in touch with his Korean roots, learning the language, and studying abroad in Seoul. Beyond that, Shin simply found CEAS welcoming and engaging.

“My favorite class at Wesleyan was Professor Watanabe’s samurai class [CEAS217: ‘Samurai: Imagining, Performing Japanese Identity’],” Shin said, which elicited a smile from Watanabe.

Shin then introduced and performed his 2020 song “Soju Over Ice,” which mixes Korean and English lyrics. A laid-back party anthem, “Soju Over Ice” humorously laments the fact that the titular Korean liquor, quite cheap in South Korea, is far more expensive in the United States.

At 3 p.m., Shin joined an intimate group around a table in the CEAS lecture hall for a creative writing workshop. Shin began the event by distributing copies of the lyrics to his new song, “OVERCAME,” a raw track whose instrumental blends the guzheng, a traditional Chinese instrument, with trap beats and lyrics that discuss racism and anti-Asian violence. Shin then played the song and opened up the room for discussion.

Joy Rhoden ’92 P’25, who attended the event alongside her son Nolan Lewis ’25, questioned a lyric in the song where Shin raps that he was once “fearful of the Blacks.” Shin explained that that lyric reflected the prejudice he had to overcome, having internalized advice he received from family members as a child to be wary of Black, low-income areas. He went on to share that this was far from his current viewpoint, and that his upcoming album would trace his personal evolution on understanding racism.

“As an Asian American rapper, I recognize that I’m a guest in this space [of hip hop],” Shin later wrote in a text to The Argus. “I do my best to show that gratitude by studying Black history, music, and culture and also stay in touch with these communities. With that said, many in the Asian community and some of my own relatives hold prejudices against Black and Brown people…. I try to show people [both] my problematic high school self but also the progress that I made. My hope is that this raw honesty will invite others to be real and show empathy for each other’s complicated, nuanced stories.”

Shin also explained what he sees as the connection between anti-Asian and anti-Black racism, and what he views as an opportunity for these communities to come together.

“Anti-Asian hate is despicable and I’m angry as hell about it,” Shin wrote. “And yet, it has provided us an opportunity to find common ground with those that we’ve been pitted against since the founding of this country: Black people. I intend to make the most of this moment to shift the culture to being a more tolerant one through my voice in hip-hop.”

Shin also expressed his intention to explore his own flaws, and find the good even in grim situations. Some of the lyrics in “OVERCAME” discuss an incident from when Shin was only thirteen, in which he was beaten by a white man, the father of a girl he was seeing at the time.

Shin’s lyrics explore moving towards a perspective based in love and forgiveness, as he closes “OVERCAME” by moving past his grudge towards that man:

“To the man who tried to break me, as crazy as it sounds, I’ve gathered enough love for you, too.”

Shin also spoke about the more technical details of how he writes lyrics for songs, sharing a humorous detail about a critique his mother, a writer herself, would give his lyricism.

“She would always tell me to stop swearing in my songs, because [to her,] that’s being a lazy writer,” Shin said.

Lewis, who, like Shin, is a rapper, singer, and songwriter, expressed a similar point of view, sharing that, while he isn’t opposed to profanity, sometimes one can be more creative when writing around it.

“[Growing up,] I liked clean versions of songs that had different lyrics,” Lewis said. “That requires more effort and energy.”

Shin and Lewis also swapped contrasting perspectives on the therapeutic value of art. Lewis noted that for him, writing is therapeutic in nature, while for Shin, therapy helped him get in touch with his emotions, allowing him to tap into them while writing songs.

A Fiery Finish at Mic Check

Shin’s last event of the weekend was an appearance at the sixth installment of Mic Check, a student-run concert series organized by Leevon Matthews ’23. A rapper himself, Matthews organized the first Mic Check in February, with the aim of creating space for hip-hop and R&B artists at the University.

Held at Malcolm X House, the bill featured performances from DJ DoubleA (Abbi Abraham ’23), Tiah Shepherd ’23, Black Raspberry, a large ensemble led by Neo Fleurimond ’24 that describes itself the University’s first all-Black music group, Matthews, and performers from the X-Tacy group of FXT, the university’s hip-hop dance organization, including Brianna Johnson ’24, one of the group’s leaders.

Shin was the penultimate artist of the night, beginning his performance at around a quarter to midnight. Following a set from Matthews, Shin kept the energy going, beginning with the upbeat track “Sky is the Limit,” performed alongside fellow musician and producer Tyler Fabian, who provided fiery ad-libs.

Shin shone during his eight-song set, performing with charisma and feeding on and channeling the crowd’s energy. While his talent was already evident from the performance earlier in the day, at Mic Check, Shin was truly in his element, complimented by the booming sound system, colorful lighting, and enthusiastic audience. After Shin wrapped up his performance with recent single “MR. CHINATOWN,” which featured assists from Fabian and Sebastian Chang, a singer, rapper, and producer who worked with Shin on multiple recent tracks, the crowd cheered for more. Though Shin didn’t do an encore, another high-energy performance from the dancers of FXT was a strong way to close the night.

Shin learned about Mic Check through his efforts to learn about the current music scene at Wesleyan, and reached out to Matthews, wanting to share a stage with a current student artist. Shin was the first alumnus to perform at Mic Check.

“I wanted to reach as wide of an audience as I could and have people who were just really big fans of the genre, of hip-hop and rap,” Shin said.

“Coincidentally, Mic Check was planning to put on an event the day of his show, so we decided to bring him on,” Matthews wrote in an Instagram message to The Argus. “Having him come to Mic Check really expanded our mission, only reinforcing our commitment to connecting artists from different cultures, mediums, and even graduation years. He had an amazing performance and we would love to bring him back!”

Shin’s presence at homecoming involved an array of events that took me from a sunny lecture hall to a sweaty basement, inviting reflection on the history of Asian American life at the University. Shin began his weekend at AASC, discussing feelings of solitude alongside Wu, the sole Asian American student in his graduating class, and Samuel, the first tenured Asian professor at the University. He ended the weekend at Mic Check, in a room packed with dozens of students of different backgrounds all jumping along to lyrics celebrating Asian pride. Continuing this reflection, Samuel’s anecdote regarding Boon Tan was a sobering reminder of The Argus’s complicated legacy, one that prompted me, as an Asian American Editor-in-Chief of The Argus, one of many to hold that role in recent years, to look back on how this very paper’s relationship to the University’s Asian American community has shifted.

It was a truly meaningful homecoming weekend, which, though things today are by no means perfect, served as a reminder of the strides Asian Americans have made on this campus.

Oscar Kim Bauman can be reached at obauman@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply