An anonymous group of students hung a banner outside of Usdan University Center in the early morning of Friday, Oct. 14, protesting the authoritarian regime of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The banner replicated two banners hung on an overpass in a rare act of political protest in Beijing, China on Thursday, Oct. 13. The original banners spurred a wave of activism worldwide, as Chinese students used posters, flyers, and banners—including the one in Usdan—to spread the message of dissent on hundreds of university campuses across the United States and around the globe.

“No more COVID tests, we want food. No more lockdowns, we want freedom. No more lies, we want dignity. No more cultural revolution, we want real reform. No more glorious leader, we want suffrage. We are not slaves, we are citizens,” the banner read, replicating the message of the original protestor.

Hours after it was first hung, the banner was removed. According to the anonymous group, the Office of International Student Affairs (OISA) also received a report about the banner. OISA Director Morgan Keller referred the group to Associate Vice President and Dean of Students Rick Culliton, who then approved a proposal for the banner to be displayed inside Usdan until the following Friday, Oct. 21.

Associate Director of Auxiliary Services Rachel Prehodka-Spindel explained that the banner was initially removed because it violated a University policy.

“It is a violation of Usdan and University Policy to hang banners on the outside of buildings (or anywhere without approval),” Prehodka-Spindel wrote in an email to The Argus. “Later that afternoon, I received communication that the banner had been approved by Student Affairs via a Symbolic Structures Request resulting in the indoor location. It was approved to be displayed for one week, at which point it was removed.”

On Monday, Oct. 17, an unknown student cut down the banner from Usdan’s second-floor balcony, but Usdan student staff were able to retrieve it. The banner was rehung in Usdan for the remainder of the week until Friday, Oct. 21.

The original protest in Beijing happened days before President Xi Jinping secured a third term in power in a Party Congress session in the same city. China’s online censorship quickly moved to restrict all references to the protest. The group involved in creating and hanging up the banner said that the protest was an unimaginable moment that inspired them to be able to take action. The group spoke with The Argus together and requested that quotes be attributed to the group as a whole.

“For me, in my whole life, I’ve never seen any banner back home, or any rally at all,” they said. “It’s never occurred to anybody that [such an act] is possible, it is unimaginable. We always wanted to speak up, but we never imagined how, or imagined anyone doing that. But [the original protestor’s] action gave us the power so that we can imagine doing this too, here or anywhere else in the future.”

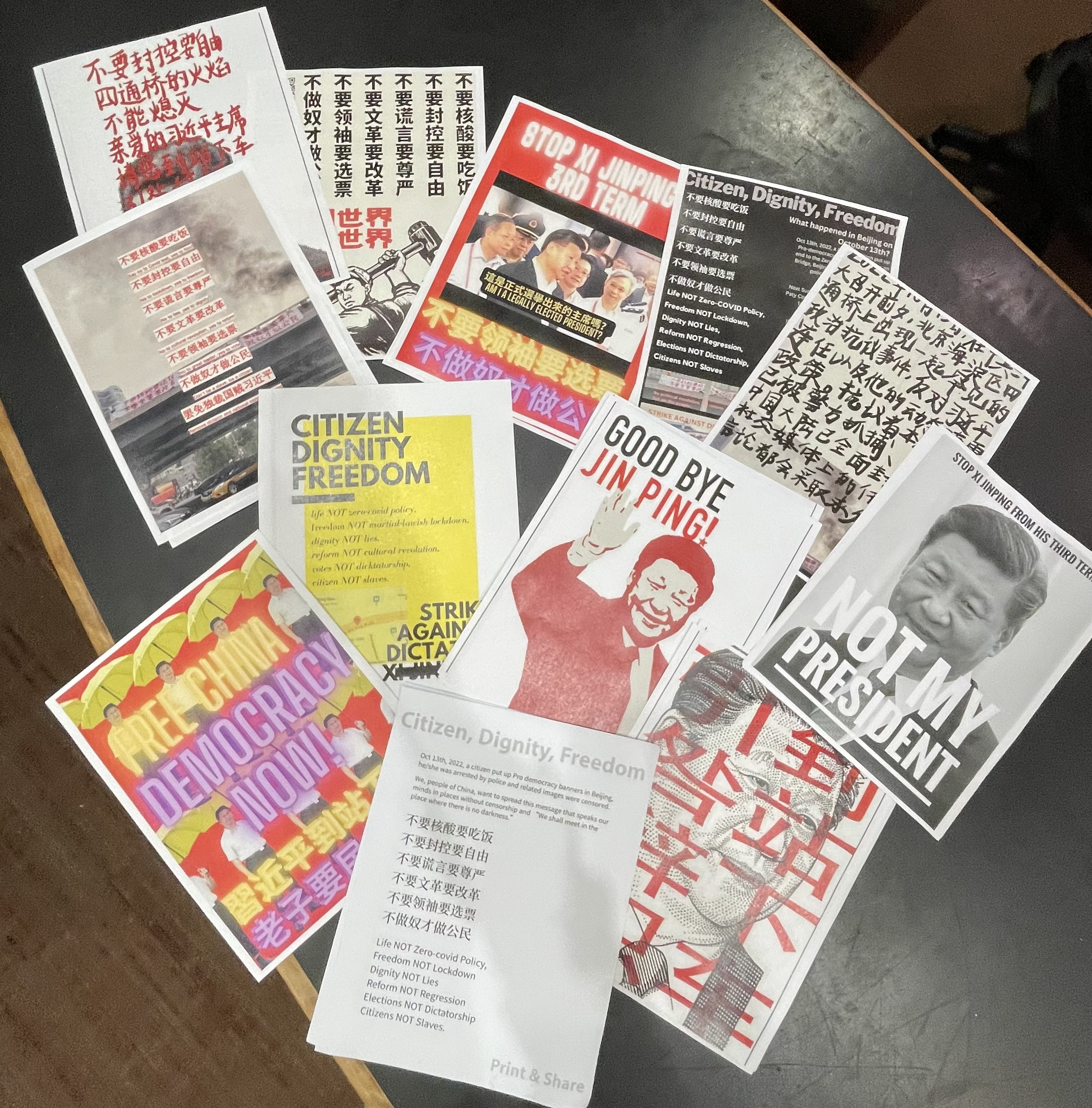

Other students who were not a part of the same group also began to up posters around Wesleyan’s campus, alluding to the original banner, explaining its context, and advocating for transnational resistance to dictatorship, oppression, and violence. The group said that while they did not know the identities of the other students who put up posters, they resonated with their shared feelings.

“It’s not like a unified [group of] us did everything on campus related [to the banner], and I honestly don’t know who put up a lot of those posters,” they said. “I guess it’s better that we don’t know each other, but [we are] also supported and encouraged by each other through this flow.”

One anonymous student who put up additional posters, but was not affiliated with the group, echoed their sentiments.

“It’s just safer to remain anonymous, considering the possible persecutions that we might face back home if the [Chinese] authorities found out that we were part of these anti-government protests abroad,” the student said.

The group reflected that seeing similar actions on other university campuses helped them feel like they were a part of a bigger movement led by Chinese students around the world.

“That’s the moment that I realized it’s not just us doing this,” the group said. “[It was] huge in the Chinese international student community.”

While creating the banner, the group grappled with the tension between copying the words from the original banners in Beijing and their desire to connect the protest to transnational action and oppression, along with advocating for other marginalized groups.

“It’s someone else’s language that we are borrowing here to express or to narrate what’s happening, and I just felt, on the one hand, I want to [spread their message], but on the other hand I felt like I was alienated in a sense by the [same] words,” they said. “The question was how to repeat someone, replicate something others said, but also put your own voice in. So later on we did some…posters that use the same grammar or the syntax as the original protest banner but include additional topics of concern, like ‘we want to be queer.’”

The group shared that the hanging of the banner sparked conversations within the Chinese international student community at Wesleyan. In particular, they noted the reaction of first-year Chinese students, many of whom are still adjusting to life outside of China.

“Before [coming to Wesleyan], they all lived in China their whole life, and the firewall definitely is the reason for the information gap,” they said, referring to the Chinese government’s censorship effort that blocks access to selected foreign websites. “Amongst the freshman community of Chinese students, the majority of them don’t talk about it at all, even though they’re just sitting down under the banner and it’s such a huge thing happening in the country. Some of them said: ‘We’re so used to self-censorship and I can’t think of any other option.’ [I don’t blame them] for indifference…. It’s not a negative [thing].”

The original banners hung up in Beijing called out of the Chinese government’s “zero COVID” policy, which has enforced strict blanket lockdowns across the country, disrupting residents’ daily activities and access to essential goods and services, including food. The policy has taken a toll on the Chinese economy, affecting households and small businesses. The group spoke about how the original banners’ reference to COVID-19 policies likely served as a shared point of concern that also captured other frustrations among Chinese citizens.

“I think that the zero tolerance [COVID-19] policy—this is just my speculation—but I feel it’s something that accelerates or [is] a more condensed manifestation of the state violence in recent years, about which many people had very strong feelings for the first time in their lives,” the group said. “I guess people can identify with that [frustration] more, but I don’t think the problem is only with that one policy. It’s frustration and trauma built up from before.”

The group shared that ultimately, they hope to create space in the University for students to reflect on their experiences and the intent of the protests through the banner.

“It doesn’t matter, at least to me, what specifically is on the banner,” they said. “I want it to occupy space, to create a space that makes Wesleyan at least a little bit safer for people, not for them to change their political views, not for them to just say ‘I’m now anti-CCP,’ but to have a little bit [of] sensitivity and empathy to reflect on their experience, reflect on this unspeakable, uncomfortable moment.”

One major part of the group’s intentions in hanging the banner and raising awareness of the original protest in Beijing was to draw attention to international students who are displaced from their homes, highlighting the transnational nature of their identities and experiences. After hanging up the banner, they recounted meeting and talking to other international students who have also had experiences with living under authoritarian governments outside of the United States.

“One thing I wanna bring in is to just highlight the kind of liminality of diasporic students here, how they carry the weight from back home and then also experience the state violence here in the U.S.—colonialism, racism, and how to navigate that space,” they said. “People assume, ‘Oh, everybody has the same academic freedom, I don’t even know why people care so much about stuff in China.’ And by diversifying the narrative, I also hope to include people from other regions, because…problems of authoritarianism and patriarchy, those kinds of violence are transnational, and we used this instance to make friends with people who are impacted and identify with this bodily experience of dealing with state violence.”

Following the hanging of the banner, a Transnational Support Space was organized for students to share and discuss their experiences with these issues. The event was held from 7 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. at the Resource Center on Thursday, Oct. 27, and marked the first of what organizers hope will be a gradual building of transnational solidarity among students on campus, especially among international students.

“We were talking about this common experience of us international students,” the group said. “We feel alone and isolated and [ask ourselves], ‘Why [are we] doing stuff in the US [when we should be] dealing with [events] back home?’ I feel like a lot of international students do resonate with that, but because our social circles were separated, we never had that conversation before.”

Reiterating the idea of experiencing being away from home as a liminal space, the group highlighted the struggles they faced in wanting to take action while being in a place that is entirely different from their home country.

“For me, often when I call my parents, they would say, ‘Why would you care? You are not in China. You are privileged and you go to the U.S. and you study there and you don’t have to wear a mask and you don’t have to stay home. Why do you still care?’” they said. “It sometimes hurts and kind of sanitizes me as a Chinese person, [and] it probably also ties with a lot of discussions on the identity struggle of overseas students, certainly Chinese students, studying in a country which has the totally opposite ideology or political stance from their home country.”

The group hopes to keep the momentum of the wave of protests around the world going.

“I wish [this] could be part of an organizing effort in that we could keep the conversation going, we could open up space to include more people, we could keep the momentum going,” they said. “During the process, we support each other, care for each other, or even just provide food for each other. That is also part of the momentum for me.”

Jem Shin can be reached at jshin01@wesleyan.edu.

Sida Chu can be reached at schu@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply