Content Warning: This article contains references to crime and murder.

Welcome to Office Hours, a series brought to you by the Features section! In these articles, Argus writers speak to faculty, staff, and administrators about their interests, classes, and lives on and off campus.

Assistant Professor of History and East Asian Studies Ying Jia Tan knows the importance of using his work to expose the truth. Fresh out of college, Tan covered the crime beat for a Chinese-language newspaper in Singapore. He visited crime scene after crime scene, but one case stood out. A woman was found dead in her home, and while the police presumed that she died from suicide, her neighbors suggested otherwise. After speaking to the undertakers who had dealt with the woman’s body, Tan was sure it was a murder case. He wrote the story and published it.

“The official authorities don’t always tell you the whole story; they have every incentive to hide and conceal,” Tan said. “The person who provided us with the most important piece of evidence was the undertaker, and this person, we never give a second thought to.”

Through his investigation, Tan literally found a “body of evidence” that undermined the story authorities maintained. Now, as a professor, this experience of finding and sharing the truth remains central to his work. Whether he’s investigating a murder or diving into historical research, Tan knows how to dig for the truth.

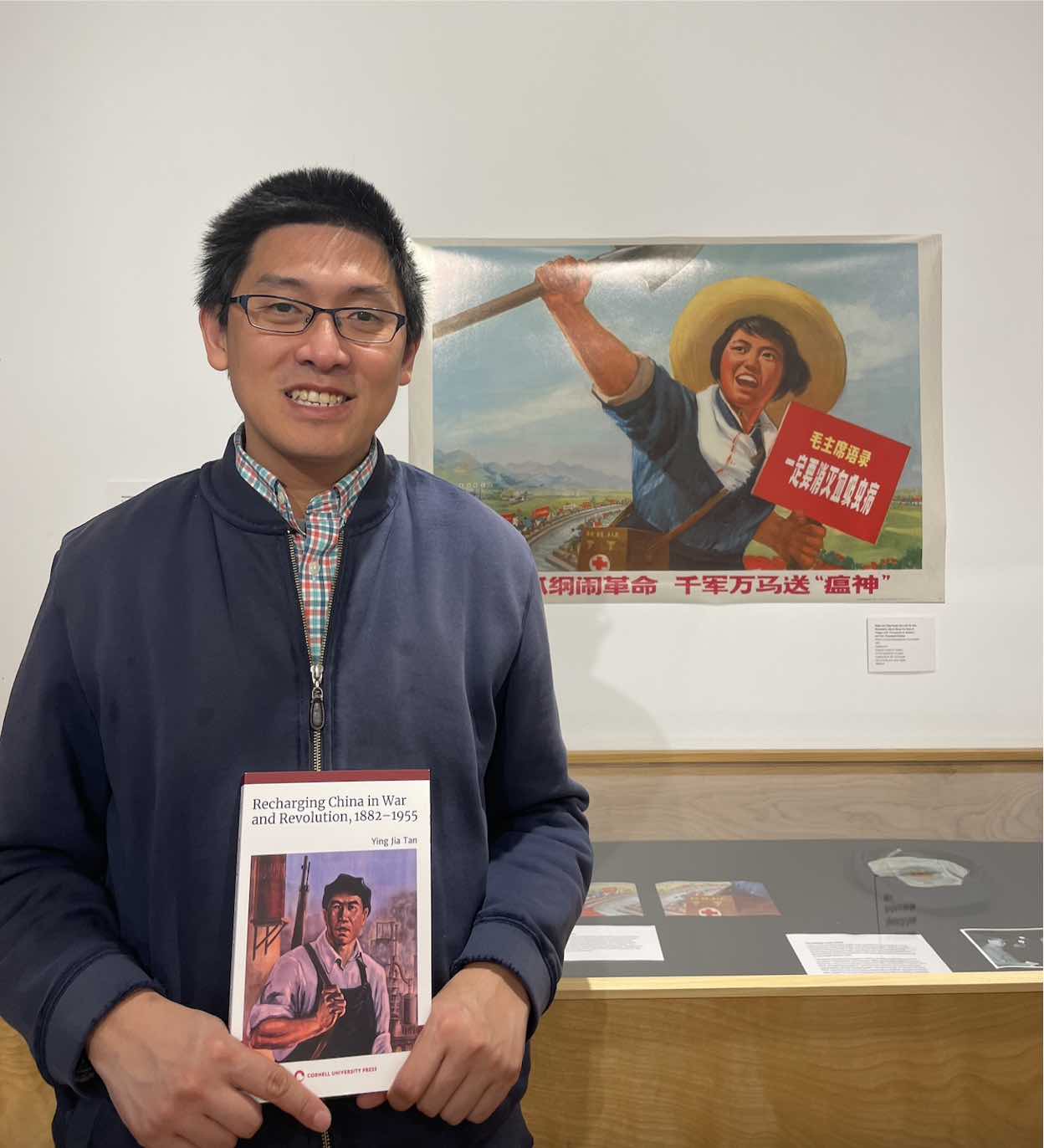

Tan began working at the University in 2015, concentrating his research on the history of energy (and energy disruptions) in modern China. Just last year, he published his first book, “Recharging China in War and Revolution, 1882–1955.” He continues to teach classes on the topic, such as “China as a Scientific Powerhouse,” “Modern China,” and “Pirates, Traders, and Colonial Settlers in Maritime East Asia.”

This semester, Tan spearheaded an exhibit called “Strong Bodies for the Revolution: Pursuing Health and Power in the People’s Republic of China,” which is on display in the CEAS gallery until Saturday, May 21. Despite his busy schedule, Tan found time to sit down and talk about his career, passions, and life outside the classroom.

The Argus: What drew you to become a professor?

Ying Jia Tan: As an academic, I feel that I’m learning something new every day. This is not something that I could say when I was a journalist.

A: What is the number one thing being a professor has taught you?

YJT: Be ready to be proven wrong.

A: When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

YJT: A chemistry teacher. There is always something magical about the laboratory and mixing up stuff.

A: What was writing a book for 10 years like? How did you stay motivated?

YJT: It felt important to write a book about electricity in China—there were earlier reports written in the fifties and sixties, largely intelligence reports—but it’s a topic of great importance if we think about the role of energy and geopolitics. The other thing that largely motivated me was students at Wesleyan. I was really excited by the questions they were asking me.

A: What is one thing that students don’t know about you?

YJT: I’m teaching a Mandopop (Mandarin popular music) class next semester. I enjoy singing, going to karaoke, and my favorite songs are songs in the Taiwanese dialect. I actually can sing better than I speak the dialect.

A: If you could live in a time period of the past, when would it be?

YJT: Hands down, 11th-century Kaifeng, so Song Dynasty China. This was a time of great political freedom, a time when intellectuals played a very important role in shaping official discourse. This was also a time of great luxury. It was a time of political crisis and a time to challenge the political order.

A: Tell me about “Strong Bodies for the Revolution.”

YJT: Two years ago, I was leading a class visit for Professor Smolkin’s class [“The Communist Experience in the Soviet Union”] and we brought out the original posters in the College of East Asian Studies. It was a really engaging experience. I think students got a lot out of looking at these posters up close, and we thought that the poster exhibition was something we absolutely had to do. As things opened up by Fall 2021, we started planning for the exhibition. The title for the exhibition came to mind when students were falling ill, and there’s a Chinese revolutionary slogan which is quite literally “the body is the seed money for the revolution.”

The exhibition is a teaching collection. It is designed in a way that we could actually teach a class there. The posters are not just objects on the wall. We’re actually supposed to engage and speak with it, and we’re supposed to criticize it.

A: Do you have a mantra?

YJT: This is something I tell all my thesis writers: “Embrace your subconsciousness.” There are things that are always lurking in our minds that we’re not aware of, and we’re being exposed to all these things, and our minds are subconsciously latching on.

A: What is on your bucket list?

YJT: Drive coast to coast.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Halle Newman can be reached at hnewman@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply