c/o Jonathan Daniel, Getty Images

Major League Baseball (MLB) has once again fallen flat on its face due to a crisis of its own making. On Dec. 2, the league’s Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA), which governs the league’s relationship with the player’s union, the Major League Baseball Players Association, expired. As a result, the league, representing the owners of its 30 franchises, imposed a lockout, effectively barring any contact between teams and players until a new CBA is negotiated.

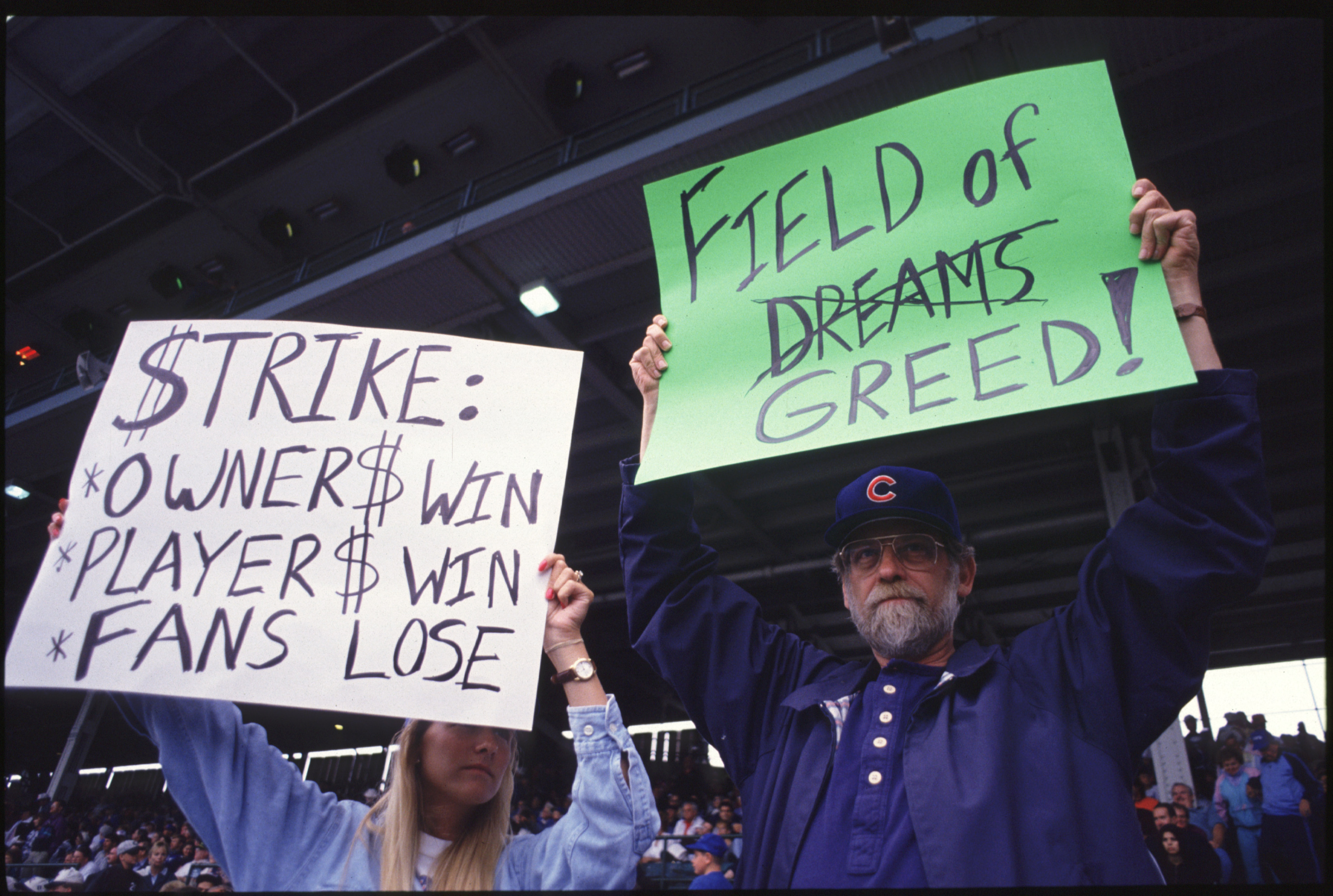

In the meantime, however, what is now the ninth work stoppage in the history of professional baseball has the potential of turning very ugly, very fast. With players and owners gripped by years of residual tensions and grievances, this lockout shows no signs of stopping soon. At stake is the interest of millions of fans, who may finally have the motivation to leave behind this floundering sport for good. In a fight that pits millionaires against millionaires over millions of dollars, the biggest losers won’t be the players or the owners, but the fans that are forced to deal with the second jeopardized season in three years.

The biggest sticking point between the league and the union at this point centers around service time and free agency. Currently, most players reach free agency after six years of service time, often leaving them around the age of 30 before they can first enter the open market. As a consequence, however, most players have reached their statistical peaks in their mid-to-late 20s before they ever get a chance to seek a market-value contract. Savvy, analytics-focused teams have begun to exploit this system by increasingly choosing to replace all but the most talented stars with young players on team-friendly deals, rather than offering veteran players a second or third contract. Naturally, to a union where older, established players are overrepresented in sway and stature, the continued existence of this trend is non-negotiable.

Players are also frustrated by service-time manipulation, in which younger players are strategically sent down to the minor leagues in order to deny them additional service years. Under MLB rules, a player must be on an MLB roster for 172 out of 187 days in order to accrue a year of service, bringing them closer to the pay raises that often come about as a result of arbitration and free agency. A common practice among teams, however, is to delay free agency a full year by keeping talented rookies in the minor leagues for precisely 16 days, keeping them locked under team control on an affordable salary for a greater period. The players present legitimate grievances when it comes to the way in which the league manipulates contracts and restricts player choice all to save the owners, many of them already billionaires, a few extra dimes.

It may be true that players have been getting the short end of the stick recently, with analytics helping to displace veterans that typically would have enjoyed a long (and profitable) career in the league. It’s also true, however, that the players have far from cooperated in any sort of meaningful way with MLB’s desire to modernize the game. In addition to economic concerns, any new CBA will likely have to address the ballooning time that games have begun to occupy. Last season saw a new record for the average time needed to complete a nine-inning game, with over 3 hours and 10 minutes needed between the first pitch and final out. Keeping in mind the already limited periods of intense activity in a baseball game (in 2013, the Wall Street Journal estimated only 18 minutes of actual action per game, and that’s before the analytics-guided movement toward true outcomes reduced the number of balls in play even further), and baseball games can become drowsiness-inducing slugfests. As a result, baseball has steadily ceded its status as America’s pastime to other sports, ranking a distant third behind football and basketball as Americans’ favorite sports in Gallup polling, and is in real danger of dropping behind soccer in the coming years as well.

MLB is certainly aware of the peril its monstrously long contests pose to the future of the sport; that’s why, over the past few years, the league has proposed a slew of innovations, such as a pitch clock, reduced mound visits, and automatic intentional walks to speed up the pace of play. Aside from the changes to the intentional walk rule (which is highly situational in the first place), the players have refused to accept any changes, either due to an excessive commitment to tradition or spiteful obstinance with regards to the league. If players want to receive a bigger slice of the financial pie, then winning in the court of public opinion is vital; focusing on relatively low-salience issues like service time, rather than a problem affecting every fan of the game today, is a bad place to start.

All of this labor strife takes place against the backdrop of the 2020 season. Unlike the National Basketball Association (NBA) and National Hockey League, which were in the middle of their seasons when alarm over COVID-19 first began to spread in the United States, MLB was still in its offseason, with regular-season play typically not beginning until April. As an outdoor sport that can be reasonably adapted to accommodate social distancing, baseball seemed as likely a candidate as any to herald the return of live sports in the United States. Naturally, given the preexisting acrimonious relationship between players and team owners, this failed to come to pass. Owners, seeking to protect against lost revenue from hosting games in empty stadiums, wished to limit the number of games played, while players, who faced prorated salaries for each missed game, were set on playing as many games as possible. Secondary to both parties was the reality of a global pandemic that most certainly gave fans more important things to worry about than the pocketbooks of wealthy fanboys and grown men participating in a recreational activity for their job. MLB was only able to salvage its season when Commissioner Rob Manfred unilaterally imposed a 60 game season with play beginning on July 23, 2020. Despite using pre-existing facilities, professional baseball only returned a week before the NBA managed to do so itself in a newly-constructed sealed “bubble” in Walt Disney World.

Neither MLB nor the players’ union have done much to ingratiate themselves with fans in the past few years, and a work stoppage is hardly an effective solution. The last time the league failed to secure labor peace, a players’ strike wiped out the 1994 World Series and forced the National Labor Relations Board to seek an injunction against the owners (one that was ultimately granted by current Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor). The 1994 strike did significant damage to the game, arguably beginning the downward spiral that has left more members of Gen Z fans of esports (35%) than baseball (32%).

When it comes to the 2021 lockout, fans may not realize the intricacies of the issue with labor negotiations. All the average American will see is filler content on their television screens where game should be playing, and no service time or pace of play adjustments are going to undo the lasting harm an extensive work stoppage will do to professional baseball in the years to come.

Drew Kushnir can be reached at dkushnir@wesleyan.edu.