c/o imdb.com

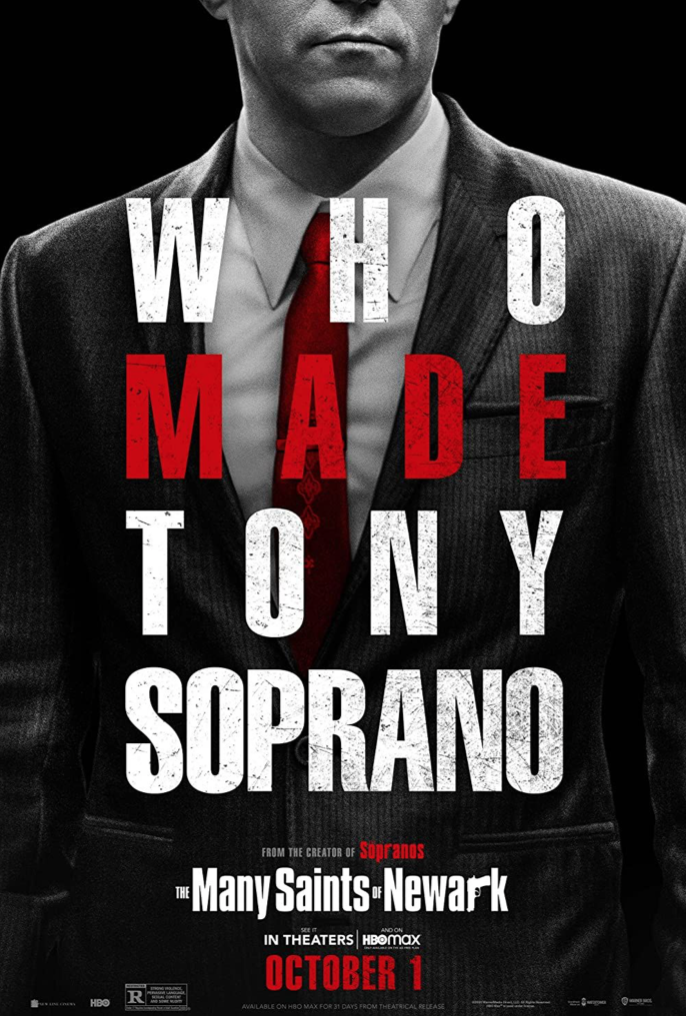

“The Sopranos” defined modern television, ushering in the era of prestige TV: shows with shorter seasons, tighter stories, and higher budgets. In essence, “The Sopranos” showed that television could be as good as the movies. Now, the show, which aired its last episode in 2007, has a prequel film, titled “The Many Saints of Newark,” which was released in theaters and on HBOMax on Oct. 1.

The plot follows Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola) and his operations within the DiMeo crime family. His father, Hollywood Dick (Ray Liotta)—the Sopranos world always has bizarre names—brings home a woman named Giuseppina from Italy (Michela De Rossi). Conflict builds between father and son as Dickie falls in love with Giuseppina.

Meanwhile, a Black associate of the family named Harold (Leslie Odom Jr.) grows angry toward the racism and exclusion that define his dealings with the Italians. Some of the movie is set against the backdrop of the 1967 Newark riots, five days of civil unrest sparked by the arrest and beating of a Black cab driver. Harold starts his own rebellion, setting up a Black crime ring to compete with the Italian mafia.

The tension between Harold and Dickie carries most of the story, while a younger Tony Soprano (the protagonist of “The Sopranos”) lurks in the background. Tony looks up to Dickie, while his father is largely absent and his mother (an accurately paranoid Vera Farmiga) succumbs to mental illness. As a child, Tony is played by William Ludwig, until Michael Gandolfini (son of the original Tony Soprano, James Gandolfini) takes the stage to portray adolescent Tony. Like many teenagers, Tony plays football and wants to go to college, but he also runs a betting ring for sports with kids in school. The last half of the movie plays with the dramatic question: where will Tony Soprano end up? Will he become a gangster?

The audience, of course, already knows the answer to this question, and there’s a powerful idea at the core of all of this: can a mobster truly repent? Dickie is trapped in his own crimes, desires, and sins. Young Tony has some hope, but we know he’s destined for the same life. It’s not the American Dream; it’s the American cycle.

Nevertheless, each of these ideas was explored better in the show than in the film. Some moments are visually powerful, but they never have enough time to breathe and give them weight in the story.

A scene from the first season of the show, in which Tony witnesses his father shoot a man, is recreated in the film. In the show, the scene is gut-wrenching because it’s given an entire episode’s worth of context. In another scene, young Tony watches as his father is taken to jail. Present Tony talks about it with his therapist, Dr. Melfi. We learn about his father. We see how Tony’s son might be repeating his entrenched behaviors. In the movie, the same scene and sequence of events is barely given a moment to land with the viewers before the film cuts to a scene of the Newark riots.

During the riot scenes, viewers are treated to moments of sincere horror as the characters watch their city burn. These moments in the film are fascinating and have rich symbolic connections to the present, but they feel untethered from the rest of the movie’s narrative. Buried beneath this disjointed plotline is a movie about the struggle of Black characters, which has always lingered on the edge of the show. However, since the movie doesn’t have room to flesh out any complex themes, the topic of relationships between Black and Italian communities is left under-explored.

Younger versions of many Sopranos regulars pop up, but they never play too much of a role in the story. The thing that most tethers the movie to the show is a narration from Christopher (Michael Imperioli). The narration, however, doesn’t feel effective since Christopher’s character is so peripheral to the movie.

The creative team that brought “Saints” to life is largely the same as the team that created “The Sopranos.” The film was written by David Chase, the show’s creator, and Lawrence Konner, a regular writer from the show, and directed by Alan Taylor, a frequent director on the show. But despite this continuity, it never quite captures the highs of “The Sopranos.”

The film’s writing is its weakest point. It feels like television: it’s loose and hops between storylines. There’s never the present and evolving dramatic hook of a movie and, instead, the viewer is left with the sense of a writer juggling half a dozen thematic arcs with little idea of where they’re going. This style of writing works well on television—look at any season of “The Sopranos”—but it’s too much, too fast when crammed into two hours.

“Saints” is smart enough to be more than just an homage to “The Sopranos,” but it’s not well-crafted enough to hone a story of its own. The movie has something to say and some powerful visuals, but it doesn’t know how to be a movie. While “The Sopranos” made television cinematic, “Saints” falls short of translating the same world onto the big screen.

Jacob Silberman-Baron can be reached at jsilbermanba@wesleyan.edu