c/o Wesleyan Bystander Intervention

It’s your first week on campus as a first-year student. Along with the excitement of a new adventure, orientation, and fresh Wesleyan merch, you’re also required to complete an online training course about bystander intervention training, after which you are given a magnet that lists sexual assault resources. The training, with its colorful slideshows, awkward reenactment videos of partying, and mini-quizzes has a clear purpose according to its organizers.

“Bystander intervention empowers everyone to intervene in situations involving sexual violence and high-risk drug and alcohol use,” the slides read.

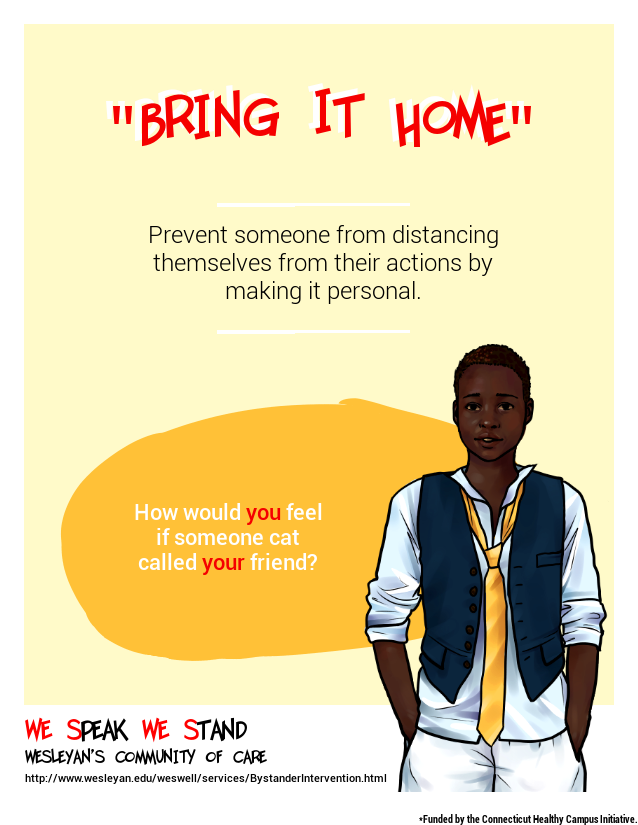

You have now been equipped with several intervention strategies, such as de-escalating potential aggressors by using distraction tactics or “bring it home” statements, like “what if someone said *your* girlfriend deserves to be raped or called *your* mother a whore.” Now, as an active member of the Wesleyan student body, you pledge to heroically swoop in to prevent the sexual assault or harassment of a fellow student. However, this feels like a lot of weight and responsibility to be putting on yourself, the potential bystander, and it is still unclear to you that you could change the situation for someone who may be vulnerable. You may also be wondering why there isn’t an online course for the future perpetrator whom you are supposed to “save” the victim from. At this point, that magnet on sexual assault resources feels like a tiny Band-Aid for an open wound.

As a member of the Title IX leadership, I’ve been collaborating with other coordinators to provide resources that are better aimed toward students and survivors, in the hope of making the process of reporting instances of sexual assault less daunting. As an athlete, I am also required to take bystander intervention training each year. However, I’m disappointed that the training ignores the fact that we live in a culture of violence; whether it be social interactions on the playground or the shows we watch on TV, there is simply no escaping it. Bystander training has long overlooked this reality. There is also the misconception that sexual violence will end if you see something and say something. But disrupting one assault is not the same thing as ending sexual violence altogether. We need to start acknowledging that sexual violence is a public health crisis and focusing on reducing violence at the population level, rather than the individual level. Indeed, the CDC released a document on preventing sexual violence that echoed these ideas.

“Brief, one-session educational programs focused on increasing awareness or changing beliefs and attitudes are not effective at changing behavior in the long-term,” the document reads. “These approaches may be useful as one component of a comprehensive strategy. However, they are not likely to have any impact on rates of violence if implemented as a stand-alone strategy or as a primary component of a prevention plan.”

Notably, bystander intervention training shifts the responsibility to a bystander who is supposed to use the tools they have acquired to prevent a situation from escalating. These “tools” don’t help solve the systemic and institutional behaviors that normalize both the violence and rape culture present across university campuses. The purpose of bystander intervention training wasn’t to end sexual violence, but was rather designed to help individuals intercede in emergency situations. The training began to spread after the Violence against Women Act was signed into federal law in 1994. The law came into effect after decades of activism around domestic violence and sexual assault and put pressure on institutions to adopt prevention initiatives. However, the goal of bystander training—to compel a bystander to intervene during an emergency—is not achieved on a large scale, because it fails to tackle our culture’s narrow perceptions of what classifies as sexual violence and harassment.

Our society does not view taking advantage of someone under the influence of substances, inappropriate grabbing, forced kissing, and even belittling or verbal sexual assault as an emergency situation. We have deemed these behaviors as excusable or normal when college students drink too much. The part of bystander intervention training focused around intensive drug and alcohol use actually relieves perpetrators of taking responsibility for their actions. At its best, bystander intervention is a last-ditch effort to remove someone from a dangerous situation. The program fails to acknowledge that these interventions are not one size fits all and that most bystanders who step in are women who can be at risk themselves. Tuğçe Albayrak was a 23-year-old college student in Germany who was murdered after helping two teenage girls who were being harassed by a group of men. Albayrak had simply followed the same instructions we pledged as Wesleyan students: to intervene. And it cost her her life.

If Wesleyan and other colleges are interested in reducing the rates of sexual violence, they should facilitate anti-perpetration programs for high-risk groups by targeting groups like fraternities or sports teams. The CDC even recommends a prevention program specifically aimed at sports teams; it is one of the only programs in the United States that has proven to reduce sexual assault on campus. The program, called Coaching Boys into Men, starts with using sports coaches to engage in conversations with young boys and men about toxic masculinity, intimate partner violence, and gender equity. Educational institutions in particular are responsible for creating a safe and equitable environment where perpetrators often go unchallenged. We need to take accountability for all of the factors that may have led perpetrators to think that their actions are acceptable, from small sexist comments to seeing what healthy relationships actually look like in everyday life. This does not mean that bystander intervention training should be scrapped altogether. Rather, we need to recognize that it is a small piece in the puzzle to ending sexual violence. A lot of this work starts internally; it takes recognizing how we have participated in this system and culture of violence to end it at a systemic level, to ensure that 20 years down the line, Wesleyan students may not need a magnet to locate sexual assault resources.

Avery Kelly can be reached at aikelly@wesleyan.edu