Every week, the Features Section publishes an interview with a particularly active, interesting, or notorious senior: the WesCeleb. But where do these people go after they graduate? In our WesCelebs Revisited series, The Argus is checking in with alums who got the special designation in the past to hear about their time at Wes and see what they’re up to now. And as always, we’re taking WesCeleb nominations for current seniors.

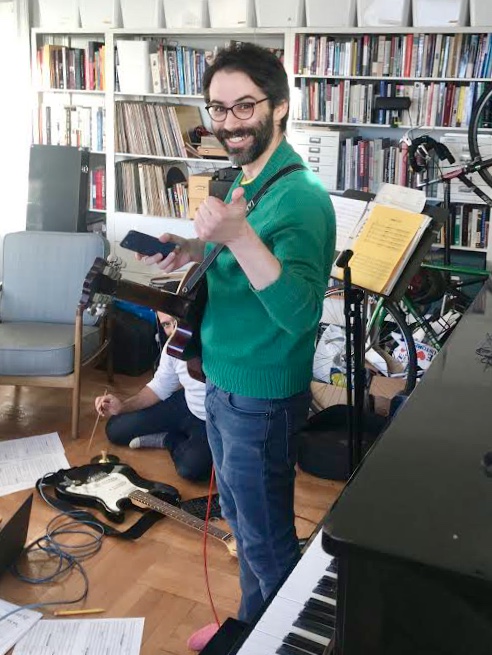

c/o Aliza Simons

In his 2004 WesCeleb interview, Dave Ruder ’05 discussed being a little self-centered, “Boogie complacency,” and the music scene at Wesleyan. Back then, Ruder was the large-bearded Program Director of WESU. Now, he’s a musician with a day job at a non-profit who’s involved in several groups and also runs a record label. We caught up recently over Zoom to hear Ruder reflect on days gone by and talk about his life now.

The Argus: First of all, what’s your memory of this interview?

Dave Ruder: The person who did the interviewing [was] Ari Brostoff [’07], I think they were the Features Editor at the time. It was October, towards the beginning of the fall semester. They were like, ‘Who should I talk to?’ and I not very subtly suggested myself.

The thing that made me cringe maybe the most was the degree to which I was very upfront in the interview and thought I was being cute to talk about being self-centered. You know, Ari is still a friend. I lived with them for a couple of years after college. I haven’t mentioned this [interview] to them, and I don’t remember the interview that much itself. I was spending a lot of time at the radio station. I think I just walked through the door and was in the Argus offices. That was maybe the only time I was ever in the Argus offices.

A: What was the music scene like back then?

DR: It was great. I mean, it was lovely. It was super formative for me. It’s still something that I draw on a lot. It was very easy to put together a show with people from campus in the Westco Cafe and Eclectic and Russian House.

I mentioned it in the interview, but God, my standards were so warped because through [the Student Budget Committee] there was a series called the Campus Center Concert series. This was in the old campus center in a really charmless room called the multi-purpose room. We got five or six thousand dollars for a concert series for the year. The people who had been doing it for years before I was paying people a thousand dollars a show. I had not done any touring as a musician myself, and so I was just like, okay, I guess three people are going to come from Boston. A group of people are gonna come from Providence or from New York or from Philly, and I guess we’ll just pay them a thousand dollars. This is what was presented to me as normal.

I would call musicians I was interested in and they would be like, ‘You want to pay us what? Oh my god, great.’ Cause usually getting paid that much, it’s something where if the music department’s inviting you if the CFA’s inviting you, then maybe you’ll make that much money. But a student concert series rarely was paying that much money.

A: You mentioned something called Boogie Club in the interview.

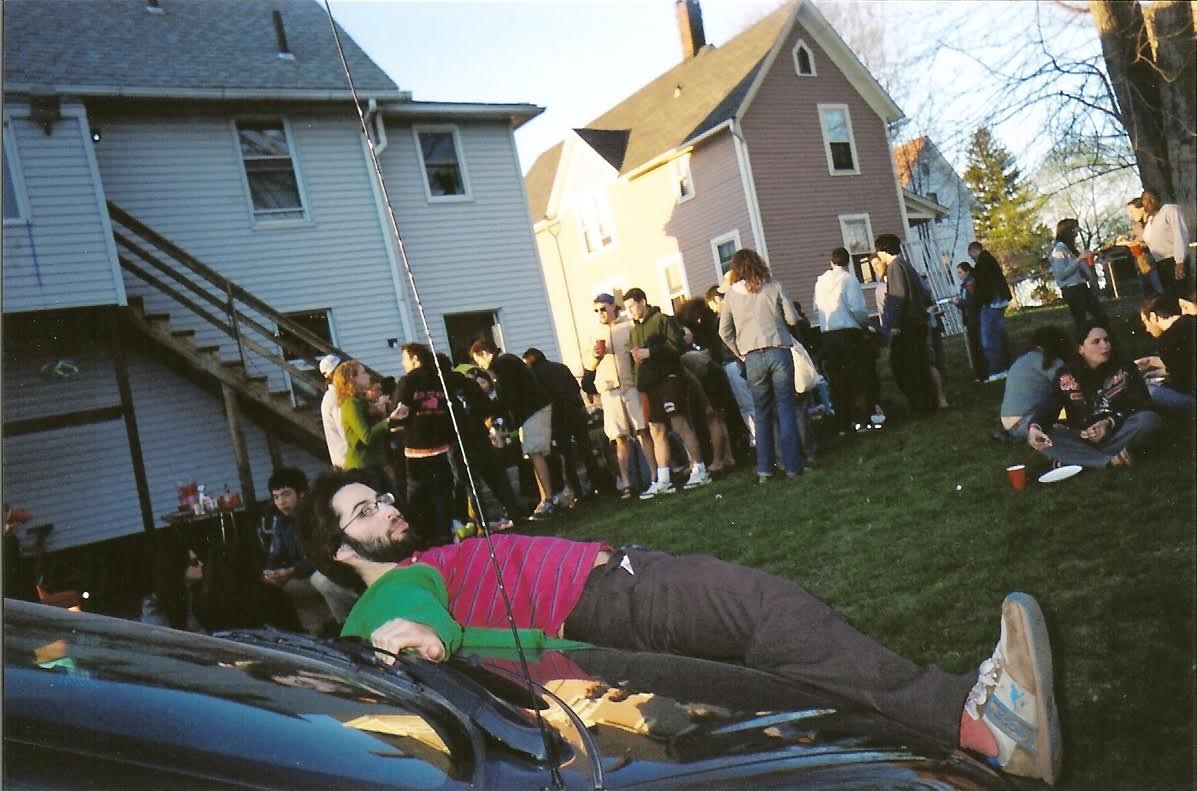

c/o Robyn Schroeder

DR: This is a very involved story. Boogie Club was started in 2001 by a guy named Tim Dutcher, who is Class of 2002 and grew up in Middletown, and Tim’s brother Jamie [’05]. I don’t know how to describe it, other than basically we would meet once a week, Saturday afternoons usually. We would eat a lot of very dense baked goods, like apple cake, and hang out at Tim’s house right by the science center [Exley]. We would bring a little boombox into Tim’s backyard and dance usually to ’80s computer game soundtracks or novelty synthesizer music from the ’60s or whatever. And then we would often fan out around campus and make these weird games or tableaus where it was people jumping. It was on one level very innocent and fun and exploratory, and also it was very useful for me—it was my freshman year, and there was a real [sense that] we were the coolest, we were like really cool. There was a certain obnoxiousness to it, which maybe you can get from the interview. Something that I very quickly tried to shed after graduating and realized about myself [was] how susceptible I had been at that age to trying to do something that seemed odd or obscure just because it would make me seem more interesting or whatever. Boogie Club was on one level really fun and innocent and on, on another level kind of more not.

A: One thing that I’m curious about with the Boogie Club thing is that you say you get put off by what you see as “Boogie complacency.” I’m not sure if you just meant that as a joke or if you were speaking to something actually in the club, but I’m really curious as to what that means.

DR: Oh my God. So I was friendly, but not like super close with a lot of people who did it my freshman year. And then it was a totally different group of people starting sophomore year when my friend Bess Thaler [’04] took it over. It became much more nice and kind and pleasant and supportive and less macho. And I think I missed it when it was more competitive or…I don’t know. I was much friendlier with the people who were involved for a couple of years after that, but there was some kind of magic that it had that first year. It became this much more fun, upbeat, positive thing. I was maybe somehow lamenting that it had less of an edge to it. Which in retrospect is ridiculous.

A: Now, you have your own record label. First question, where does the name [Gold Bolus] come from? Second question, what led you to create that?

DR: I will give you the most honest and direct answer, which is that originally it was called Small Bolus, in reference to a stool sample that I had to give to a doctor when I was 16 years old. And upon having to figure out how to shit in a cup, and then having a hard time doing it, and then driving to the hospital and giving this doctor my stool in a cup, he was like, ‘That’s it?’ waited a beat, and then was like ‘No, no, no, this is fine. It’s fine.’ And I just remember that as this particular moment of me being totally horrified. So I liked the word bolus.

It’s actually incorrect because feces isn’t a bolus, whatever. I just like internal—is that assonance? It’s not a rhyme, I know, but gold bolus, it’s the same vowel. Gold bolus sounded more optimistic than a small bolus. And I liked the idea [that] a bolus of food is not food anymore. It’s moving in your esophagus and your stomach. It’s being worked on, it’s still being digested. But it’s golden. It’s this wonderful thing, but it’s still sort of in the process. That was eventually the name.

The process of [creating the label] was I was putting out my own stuff and I was like, ‘I don’t think anyone else would ever want to release this. Nobody knows who I am. Nobody cares.’ I had done that maybe four or five times, including a couple of albums. One of my closest friends is another Wesleyan alum. We didn’t actually overlap—she’s Class of 2009. But we met through a friend. Her name is Aliza Simons. I’d put out the stuff that Aliza and I were doing together and put out some of my own stuff. In 2011/12, some of the groups that I was in started actually getting press and notice and I started actually getting paid for making music for the first time really. I had recorded something in a studio for the first time. I thought, ‘Oh, this is actually a real record. This is the first real record that I’m putting out. I should get more serious about this. And if I’m going through the process of learning how to do this, then I can tell other people around me and if they want me to try—not really knowing what I’m doing—to put their records out then great, I’ll do it.’ And now seven, eight years later I’m still doing it and I’ve actually gotten a little better at it. I sort of view it as a sort of channel of community support. There’s a lot of musicians who are kind of allergic to spreadsheets. They just want to make a thing, and then it should just go out there.

I’ve been finding particularly since the pandemic hit that my capacity to do it is lower. And that’s in part because my job is also more emotionally intense. I mean, I still work once or twice a month at a music venue in Brooklyn, even now that is just…I really value something that I had kind of started doing at Wesleyan, which was being a support person in an artistic community. Whether I’m the one making the art or not, being able to provide concrete assistance to people who are trying to do things.

A: You’re also in two other group projects. Can you speak a little about those?

DR: Sure. The Gold Bolus bullets archive is right here [gestures off-screen]. This is the main messy shelf. We have Thee Reps, which is a kind of repetitive, rough band that is somewhere between something that you could dance to and something that would be like concert music. That group’s been around like six years. And then Varispeed, which also features Aliza Simons. Actually, there are Wesleyan people and all of these groups. Varispeed is best known for performing the music of this composer Robert Ashley. We worked with him the last few years of his life and we’re performing music of his that no one else had ever performed other than him.

We also have just done a lot of bigger interdisciplinary projects that are maybe a little harder to define. We were working on a piece that we were supposed to perform a more finalized version of last year, which got canceled. There’s an artist, Peggy Weil, out of LA who made a chatbot years ago. It was just like conversations people have with a chatbot trying to convince the chatbot that they are humans. It’s a reverse Turing test. She called it a blurring test. We do sort of big, more conceptual projects.

c/o Aliza Simons

A: You work in non-profits for your day job, can you speak a little bit about what you do, what that’s like?

DR: I work at a place now called Footsteps, which is a resource center for people who have left, or are in the process of leaving ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities. I myself do not have that background, but I had heard of Footsteps and basically, my progression through working in non-profits was initially I [thought] maybe I want to run a venue someday. The first place that I worked after college was a place called Issue Project Room in Brooklyn, which is a venue. I built up a lot of experience from it. All these places where the staff was like one to five people where I was like, ‘What’s fundraising stuff, can I figure out how to do the website? Can I do all of the roles, like stage manager, house manager, tech manager?’ I wore all those hats, and I went to grad school in the middle of that for composition.

I came out feeling [that] what I want to do is, rather than just be attached to one ensemble or one venue or whatever, just to be a public resource. I worked at a library for three years. I really liked that feeling of “I have the information and I will share it with you and it’s free.” I worked at a place for four years that was about giving people resources to put on free outdoor concerts. What I wanted to be doing was directly being of more tangible service and more direct help. I realized I can’t do that in the arts, or I can’t do that with the sort of training that I have in the arts, but [I wanted] to find a social services organization that’s doing good work, where I can use these skills that I’ve developed in non-profits over 14 years.

I work on this team that does economic empowerment for people who often have the equivalent of a third or fourth-grade secular education as adults. And you know, [they] might need help with housing, might need help with financial literacy or emergency funding or help with careers. I am extremely happy working there. It’s my favorite job I’ve ever had. It’s the most supportive workplace that I’ve ever had too. In the last 11 months, I think the degree to which a lot of those kinds of workplaces have been tested, it’s great to work at a place that was supportive before and continues to be really supportive. It was really great for me. I was sort of pessimistic for a couple of years that I was ever going to be able to find a job like what I was looking for not in the arts without going back to school. And so far I have done that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sophie Griffin can be reached at sgriffin@wesleyan.edu

1 Comment

paydayplus.net

Before that, I thought that articles on this topic were not interesting, but now I have changed my opinion!