c/o wesleyan.edu

Students and faculty gathered in the Zoom-scape on Thursday, March 4 to hear a talk from journalist and memoirist William Finnegan, the latest guest in the College of Letters’ Nonfiction Speaker Series. Over the course of an hour, Finnegan addressed questions of self-awareness in journalism and discussed the unavoidable tension between expectations and truth in the field.

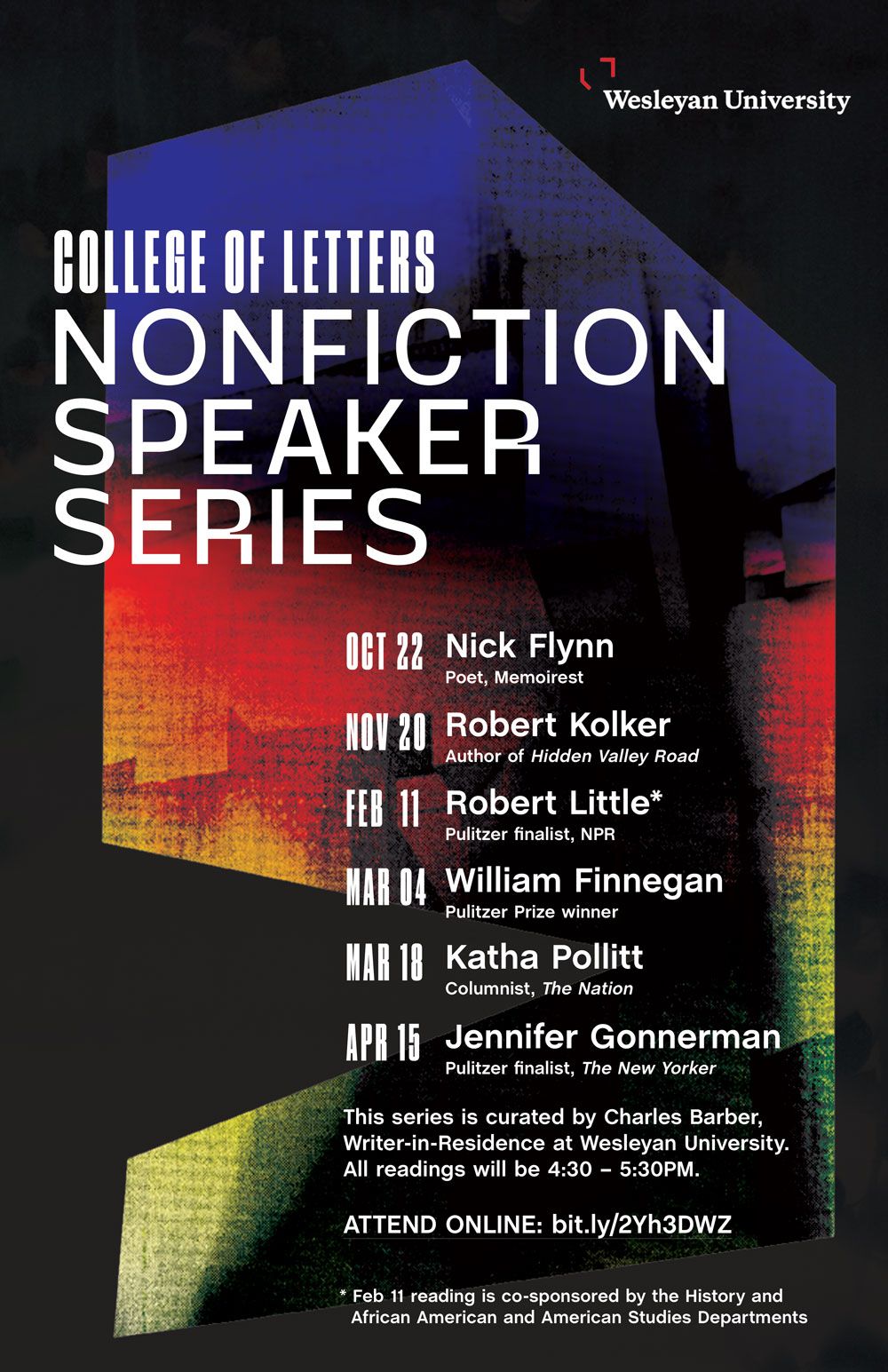

Associate Professor and Writer in Residence in the College of Letters Charles Barber, who organizes and runs this series, shared his thoughts on the scope of this year’s guests.

“What ties this rather disparate series of authors—who work in a range of genres, including reportage, memoir, poetry, and investigative journalism—together is that they all plumb social issues of wide concern,” Barber said. “They also all use the first person in their storytelling, albeit in different ways. That is, they are all grappling with their role in and their relationship to the story, with all its inherent complexities. They also all write hard-hitting stories, but with a touch of poetry and lyricism.”

In the journalism field, reporters are often expected to keep themselves removed from their writing and tell stories from a purely objective point of view. However, writers are usually personally invested in their stories simply by virtue of the amount of time and effort they’ve poured into them. Because of this, some nonfiction writers argue that to entirely remove the self from the story is to lose a valuable aspect of the truth.

It can be rare to find journalists who speak as honestly about the practice of self-insertion as Finnegan did on Thursday. Finnegan is a writer for The New Yorker and a 2016 Pulitzer Prize winner for his memoir “Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life.”

“Finnegan, who is among the more formal reporters in the series, is a master of sympathy and engagement with the people he writes about,” Barber said. “He is one of the contemporary leading practitioners of what Gay Talese called ‘the fine art of hanging out,’ the finding of the story only by spending months and months with the people he is writing about, and often finding the story in the ‘off moments,’ those chance and intimate moments that only come with such long, extended, and nonjudgmental time with the people and places you are trying to capture.”

Finnegan’s practice proves that journalists don’t exist in a vacuum. Writers are consumers of media and people of the world just like anyone else; they often go into their assignments with preconceived ideas of what they will find when they get there and what the story will be. Sometimes, they end up having an accurate prediction, but more often than not, they have to shift their frame as the story unfolds.

“The preconceptions that I approach a subject with are sometimes shaped by news coverage, sometimes by personal experience, sometimes by my own politics,” Finnegan said during his talk.

Finnegan touched on his time in Mozambique in the late 1980s, a period of intense civil conflict and violence between the government and rebel group Renamo. He went in with the “airplane theory” (the expectations you have on the plane ride there) that Renamo would be the bad guys in this story, and the government would be the force for good. After spending several weeks there and interviewing locals, he found that the actual situation was much more complicated. There was corruption and cruelty on all sides, and his job had suddenly become much harder.

“It’s been a theme through piece after piece, where I show up with one idea and have to abandon it all to start to see what’s in front of me,” Finnegan said. “A lot of times, it’s corrective and toward the truth, toward the facts, toward the difficult unearthed reality…but sometimes you’re deeply invested in that other story.”

But Finnegan made a point of saying that in essence, the job of a journalist is to abandon all other plans when confronted with the actual reality of the situation: to report on how things are, not how one expected them to be. Such an abrupt change in perspective can be disorienting, but it is a necessary and natural consequence of having a responsibility to readers as the link between them and the rest of the world.

“A good reporter…should hold their own ideas, insofar as they can, about a place or the experiences of other people at a certain distance, subject to change if the facts on the ground turn out to be not what they thought,” Finnegan said.

Finnegan also made a point of focusing on the responsibility a writer has to their subjects. For a journalist, he noted, there can be very real and potentially harmful consequences to what you choose to say. Sometimes your sources can be personally targeted, and sometimes the political context of your subject is fragile enough to merit some choices about what to include. Finnegan noted the harm that can be done simply by reporting. Thus, it is up to nonfiction writers to navigate the line between truth and morality, along with the line between responsibility to readers and responsibility to subjects.

It can be easy to take for granted the well-crafted news stories we read without thinking about the very real people behind them who work incredibly hard to keep us well-informed about the world. To hear about this side of journalism, about the actual process of finding a story and the struggle to make it true, was refreshing. It reiterated to me how essential good journalism is. News is not a straight line from source to audience; it is often a chaotic jumble of disparate information that has to be grappled with and reconciled in some way, which requires the delicate hand of a real person with intuition, compassion, and understanding of the context and consequences of their story.

This is where writers like William Finnegan, and the rest of the guests in this series, come in, with their connection to their subjects and commitment to their craft. This subtle embedding of the self in art is itself a delicate art. However this process makes stories electric and palpable, and above all, immediate and real.

The next speaker in the series is Katha Pollitt, who is a poet and a memoirist and has been a political columnist for The Nation for 30 years. This event will be Thursday, March 18, from 4:30 to 5:30.

Ella Tierney can be reached at etierney@wesleyan.edu.