Content Warning: This article contains references to racism and suicide.

i. an american experiment

For all of my life, I have wondered what race people assign to me when they see me for the first time.

The easiest way to find answers to this question would be a theatrical confrontation, an experiment that I’ve rehearsed too many times in my head. I imagine myself walking out onto a Broadway stage in front of a packed audience. For only a brief moment, a bright spotlight would pulse down from over my head, false sunlight illuminating every pore of my body. Then, after running backstage, people would have to vote on what race I am.

Maybe some audience members in the front rows would see the thick black mesh of my hair and assume that I’m either Latino or Middle Eastern. Maybe some people in the orchestra would see my brown eyes squinting under the light and assume that I’m Asian. Maybe some people further back in the audience wouldn’t be able to tell, and in their frustration would vote for “racially ambiguous.” And maybe those in the very back row of the mezzanine would barely be able to distinguish my features and assume from my radiating epidermis that I’m white.

The truth is, my race is many things. Being the son of a white father and a Filipina mother, I carry around many racial identities and labels in my being simultaneously: white, Asian, “Wasian,” Filipino, Asian American, biracial, hapa, mixed. Depending on the time of day or how far it is into the summer, my skin color changes, ripening and paling with the passage of time. I feel most Asian when I am thrown against the sharp white background of my hometown of Alexandria, Va. But I also feel most white when I fall between the softer, darker shades of groups at Wesleyan like Asian American Student Collective (AASC) or Pinoy (the Filipino group on campus). I feel most distant from myself when people come up to me speaking Spanish, assuming I’m either Mexican or Hispanic. Would it be rude of me to explain that I’m the descendent of a country that was colonized by both Spain and America?

“Where do you come from?” is the most frequent question I get on dating apps, as if I will only be attractive when made legible to their preconceived racial preferences. It’s as if knowing my race is a prerequisite for being attractive, and if I reveal myself to be Asian I will suddenly be emasculated. One time, during an immersive theater piece, I asked people to assign a color to my skin. They responded tan, yellow, olive, brown.

I’ve tried to imagine how audience members might racially profile me so many times because I’ve already played this game: I myself have been the audience member trying fruitlessly to assign races to actors whom I have seen on the stage.

This is particularly true with mixed, white-Asian actors. When I saw Phillipa Soo in “Hamilton” from the very back row of the Richard Rodgers Theater, I tried to discern if she was a person of color like the darker-skinned cast mates around her before submitting to the fact that I couldn’t tell. When I watch Darren Criss and Keanu Reeves on my television screen, I have the faintest sense that they’re like me, but when their hair is slicked back, they pass as white. When I see Conrad Ricamora performing in musicals as both Filipino in “Here Lies Love” and Chinese in “Soft Power,” it’s hard for me to assign him to any nationality. Even when actors play characters who are explicitly racially ambiguous, like James Cusati-Moyer’s role in “Slave Play,” I still find myself frantically scrolling through the actor’s Wikipedia page, trying to find their ethnicity.

Maybe this impulse to have people define my race, to have people definitively say who I am, comes from my own failures of creating my own coherent identity. While I acknowledge that existing in a liminal space of non-whiteness is an immense privilege, somedays it feels like if someone could assign me to just one race, I would always know the conditions of life I would have to be living under. I wouldn’t have to be constantly weighing my changing privilege and oppression anytime someone new entered the room; if I had just one race, I would always know what role America had assigned me.

But my impulse towards an external definition of race has been complicated recently by two groundbreaking interventions into America’s discussion of race: Isabel Wilkerson’s new book “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents” and the election of Kamala Harris as Vice President of the United States. Both of these interventions have felt like strange paradoxes, simultaneously positioning people like me in and disassociating us from America.

ii. a new cast(e) member

Isabel Wilkerson’s book “Caste” draws comparisons between the legacies of slavery in the United States and the caste system in India, aiming to reveal a system that oppresses all Americans and includes, but is not limited to, race. Although I’m not entirely convinced everyone will refuse to use race-related language in the way that Wilkerson does, the intersectionality of her argument is exciting. Wilkerson’s incisive prose is on full display in the second chapter of the book, which opens with a theatrical metaphor adapting Shakespeare’s classic phrase “All the world’s a stage.” Wilkerson imagines the population of America as a play’s cast performing their assigned races in a gaudy pageant.

“Over the run of the show, the cast has grown accustomed to who plays which part,” Wilkerson writes. “For generations, everyone has known who is center stage in the lead. Everyone knows who the hero is, who the supporting characters are, who is the sidekick good for laughs, and who is in shadow, the undifferentiated chorus with no lines to speak, no voice to sing, but necessary for the production to work.”

It’s easy to extrapolate Wilkerson’s metaphor towards roles and stereotypes many Americans are required to fill. White boys become the heroes. White girls become the damsels in distress. Black men become thugs, monsters, Emmett Tills, Othellos. Black women become maids, cakewalkers, Breonna Taylors, Venus Hottentots. Asian people become model minorities. Latinx people become bad hombres. Indigenous people become barbarians or noble savages.

But what role does America assign to me? In the white imagination, Black-white mixed race people have been consigned to become Sally Hemingses, octoroons, tragic mulattoes. But the white American imagination seems to have not even barely considered my existence a possibility. There have been brief cameos of white-Asian subjects into the modern performance canon, from the racist Oriental depiction of The Engineer in “Miss Saigon,” to the autofiction subjects of Leah Nanoko Winkler’s “God Said This,” to the devastated trans-nationalism that creates unrequited love in Mitski’s “Your Best American Girl.” But up until a few years ago, white-Asian people had been consciously left out of the American stage altogether.

This lack of damaging stereotypes for people like myself must be a part of America’s instrumentalization of Asian Americans into model minorities, supposed proof that people of color could be subservient and loyal. Cathy Park Hong phrases this strange horror in new essay collection, “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning.”

“When I hear the phrase ‘Asians are next in line to be white,’ I replace the word ‘white’ with ‘disappear,’” Hong writes. “Asians are next in line to disappear. We are so law-abiding, we will disappear into this country’s amnesiac fog. We will not be the power but become absorbed by power, not share the power of whites but be stooges to a white ideology that exploited our ancestors.”

Perhaps the most surreal example of Asian Americans’ contradictory proximity and distance to power is Harris’s election as Vice President. Like me, Harris holds multiple identities and races all at once: Black, Indian, Asian American, biracial, mixed. Because the white imagination has failed to include Black-Indian subjects, Harris has been able to use the lack of assigned role on the American stage to her advantage. She’s been able to highlight different parts of her identity according to context: she can assert her status as an HBCU grad, but also cook Indian food with Mindy Kaling, to appeal to different demographics. The deftness of Harris’s code-switching performance reached a new height in her pre-election “60 Minutes” interview, where she refuted claims that her influence in a Biden presidency might impart a socialist or progressive perspective.

“No,” she said, before bursting into a bout of nervous and probably frustrated laughter. “No, it is the perspective of a woman who grew up a Black child in America, who was also a prosecutor, who has a mother who arrived here at the age of 19 from India, who also likes hip-hop, like what do you want to know?”

What’s so concerning about Harris’s emergence as the most visible and powerful half-Asian person in history is how familiar this all feels. Didn’t Barack Obama’s tenure as president already prove that the American public wasn’t ready to see the entirety of a mixed person’s identity, instead choosing to dub him “the first Black president” because “the first mixed president” conjured too much confusion? Harris’s Indian heritage, like so many Asian American people, seems to be slowly overtaken by her other identities. It feels inevitable that it will disappear entirely, as Cathy Park Hong theorizes.

With Harris’s ascension to becoming Vice President, it seems to me that half-Asian Americans have finally been given some role to play in America. But deciding whether that role is as a protagonist or just a new version of the invisible background actor is up for debate. Looking at Harris becoming the second-in-command of this country, you could reasonably come away thinking that she has become the powerful Asian political figure Hong could not imagine. But looking at Harris achieving this position only by deferring to Biden, a white man she previously attacked in the Democratic primary, you could just as easily conclude that she has become the ultimate servant to white ideology and political power, the most fully realized form of the submissive supporting player. I’m left wondering what parts of herself Harris had to sacrifice, or render invisible, in order to achieve what she wanted.

I’m left wondering too many questions these days. Who are part-Asian subjects within America’s national cast(e), now? What roles can we possibly play in a Biden America that we hadn’t already played before? Are we doomed to achieve better and better acting roles in this absurd show, and never become the directors of our own lives?

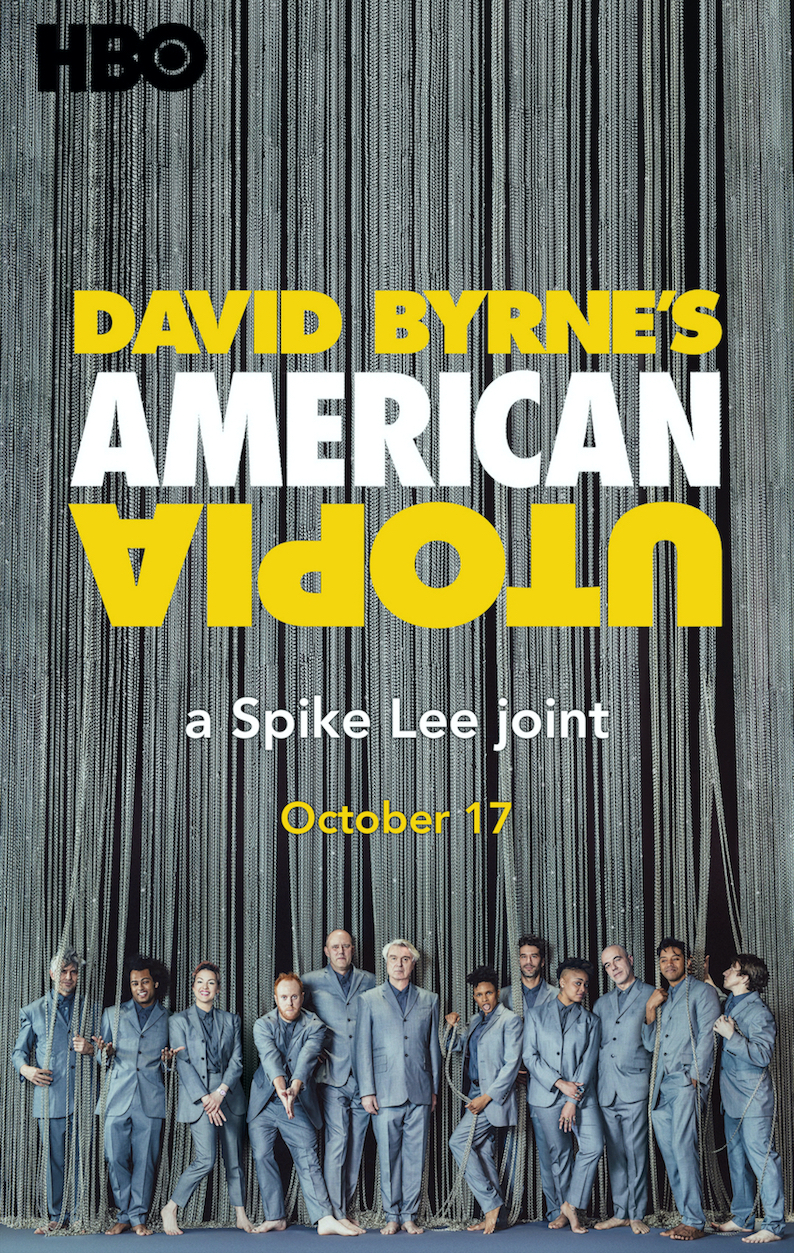

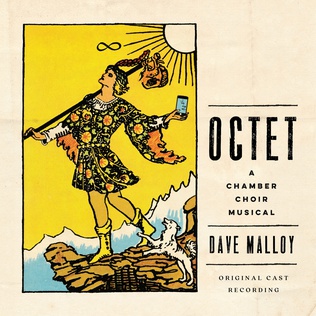

To find answers to these questions, I once again returned to theater, hearing three poignant and exciting shows online over the 2020 election week: David Byrne’s “American Utopia,” Dave Malloy’s “Octet,” and Claudia Rankine’s “November.” None of these shows center specifically around Asian American or mixed race identity, but watching other people put their experiences in front of an audience was the only way I began to stage myself in 2020. I tuned into these shows hoping to be assigned a role in America, only to discover that these playwrights were trying to tear the floorboards from the weary American stage itself.

iii. election: / before / during / after? /

When the world tells you that you don’t exist, that your race doesn’t matter, that your identity must disappear into whiteness, it’s not hard to imagine that you yourself don’t exist, that you don’t matter, that your identity necessitates annihilation. Being Asian and mixed race often feels like a quiet death wish in this country; you might never be targeted on the street for your race, but you will be excoriated for your apparent lack of one. When you walk into a space, you never know how your skin will be defined by others, a task made even more difficult when you’re young and uncertain and can’t define it for yourself.

It’s as if America is constantly repeating to people like me, “Stop being. We have no use for you, no place of subjugation, no elevated state of power. Return to the mist of confusion from which you arrived. Fade away, forever.”

When someone asks what race you are, or what Asian country you’re from, whatever answer you conjure will never be satisfactory. These questionnaires really just want you to go away, since your mere presence confounds and eludes placement. You belong to no fixed role, to no legible cast(e), to nothing. Therefore, you are nothing.

At first this is a message constantly delivered to mixed race people on the playground, at job interviews, by their lovers. But for me it became a message that I internalized to violent ends. I woke up one day this summer realizing that I wanted to dissolve, to evaporate. There was this overwhelming but deadening urge for my body and breath and self to be smoothed away until nothing of me was left. I wanted a way out.

/

One safe escape away from my current reality, an escape with strange similarity to my parents’ lives, is the filmed version of the Broadway show “David Byrne’s American Utopia” (now streaming on HBO). I grew up listening to The Talking Heads, and in my memory, “Burning Down the House” or “Once in a Lifetime” will forever be associated with my parents’ feverish, nostalgic dancing to the rhythms of their adolescence. Listening to their music always seemed like a magical transportation to the before-world I was longing for.

Watching the film, directed by Spike Lee, is an entirely different experience. Byrne has diffused his absurd, strange lyrics and music to an 11-person ensemble of Black, brown, and white musicians. Together, they form 12 disciples prophesying an unrealized utopia, not a retreat to the past as much as it is a spaceship to the future. Donning uniformly grey suits and marching around the bare stage in precise choreography, the performers take the 1980s vibe of Byrne’s work and transport it into a multicultural, harmonious, infectious vision of inclusivity.

Byrne, more than any other musician still working today, typifies for me an image of white privilege. Of course this man who sang nonsense and wore ridiculous clothes would be celebrated as a hero of experimental music, when Asian women doing the exact same thing as him in the 1980s (like, say, Yoko Ono) were derided by many white Americans as being unintelligible and bad.

Watching the Broadway show feels almost like a confession that the stage Byrne stands on, one of reified singular heroism, can no longer exist. Byrne has finally acknowledged that his weird, insular world of music cannot be just pure entertaining spectacle anymore. His answer at fixing this problem is to not demolish this lonely pedestal made for white men, but rather to widen it so that the space previously held by them can be occupied by people of color performing the same roles. It’s essentially the “Hamilton” solution: keep the same tunes, but have different bodies singing them. The hegemony and neoliberalism are softened by how much fun everyone is having reclaiming what initially wasn’t meant for them.

There are moments when David Byrne steps aside from his own discography in “American Utopia,” instead filling the space with songs by with Black musicians. The most powerful of these is a cover of Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout,” a protest song repeating the names of Black men and women murdered over the past 50 years in America: the refrain is “say his name.” Watching the song performed is a surreal experience. It is the murders of Black men, filtered through the creativity of a Black queer woman (Monae), overheard at the 2017 Women’s March by a middle-aged white man (Byrne), filtered onto stage with through multi-ethnic cast, put onto the screen by an iconoclast middle-aged Black man (Lee), ultimately watched by a mixed race man on his laptop. “American Utopia” is really about the art of translation, about the constant dance people of color must make to envision themselves in the reality where David Byrne lives.

The show ends with my favorite Talking Heads song, “Road to Nowhere,” an anthemic march towards an unknown destination. The meaning of the song also changes within the context of the show, another sort of cover. I’m reminded how Thomas Moore’s definition of “Utopia” elided with a Greek translation meaning “no-place.” The road to nowhere, the journey of the show, is a road to utopia. It is a long path towards the blank space of the show, where the world can’t really hurt you; the empty signifiers of a theater; a space of nothingness, blankness, erasure. It’s a road to whiteness.

There are no Asian or part-Asian musicians featured in “American Utopia.” But given the trans-national makeup of its cast, I think Byrne wants to say that anyone is welcome to his formerly white utopia of privilege, including me. Watching the show, I had a moment of stark shock. If I followed along with Byrne’s infectious melodies, would I just become subsumed into whiteness? Was the only way I could belong on an American stage when I was given the opportunity to by a white man? Haven’t I been “playing white” and failing to belong this whole time?

/

The night of Nov. 3, my eyes were glued to my phone and computer. Watching the election coverage that night was my own form of masochism. I knew that it was bad for me, that nothing good could come from it, that results weren’t going to be finalized, that watching it would be detrimental to my physical and mental health, that this toxic world would seep into the bunker of my room. And yet I did it anyway.

My hands jittered, moving between news sites and television channels with a kind of obsessive worship. Having exhausted all the ways I felt I could support Joe Biden, I took a turn towards the mystical. Sending energy toward the coverage trackers seemed no different than staring at tea leaves or confirming that Mercury was in retrograde. I wanted to summon some spell out of the randomness of this night. Every minute, my hands would go to reload updates on my phone. A mysterious voice sang in the back of my mind, helplessly whispering this refrain to me: refresh, refresh, refresh.

I finally recognized these words coming from the songs of Dave Malloy’s musical “Octet,” and immediately put on the original cast album. “Octet,” whose live recording comes from the 2019 Signature Theatre production, is an a capella chamber musical following a therapy session for eight internet addicts. Like all Dave Malloy musicals, the show is experimental, confounding, and utterly transfixing. Additionally, the cast is equitable: the show has four men and four women, four white people and four people of color.

Before listening to “Octet,” I had always considered internet addiction to be a uniquely white problem: while people of color dealt with murder and chaos, white people got to question why they were infatuated with Goop’s Instagram or Kim Kardashian’s ass. Malloy offers a necessary intervention into this dichotomy, exposing the ways in which the Internet only heightens the sensations of race for both white people and BIPOC. Yes, we might all be irreparably harmed by the Internet’s swirling storm. But while stakes for white people are societal and emotional shame, the stakes for people of color is life or death. All the internet does is speed up the process, an unholy catalyst for a world already collapsing.

For white characters, the internet secretes their own privilege from their subconsciouses, putting white peoples’ worst impulses on a nearly global stage. The song “Solo” tracks the confused sexual longings of Karly (Kim Blanck) and Ed (Adam Bashian) as they scroll through dating apps, the entitlement of both turning into frustration and incel terror respectively. Particularly disturbing is the song “Refresh” as sung by Jessica (Margo Seibert), recounting how her “white woman goes crazy video” has made her face recognizable to anyone on the street. We’re meant to empathize with Karens, idols whose built up virality is only meant to be torn down. But couldn’t Jessica’s fame be built on an insidious premise, like Amy Cooper’s phone call meant to have Christian Cooper, a bird-watcher of Central Park, arrested?

The characters of color, on the other hand, are hounded by feelings of despair throughout their everyday lives, which the Internet only seems to take to dire extremes. Toby (Justin Gregory Lopez) is an anti-capitalist whose feelings of disenfranchisement from the government—which probably hold some basis in reality—become twisted into conspiracy theory. The character of Paula might not have been written specifically as a Black woman, but as under the performance of actress Starr Busby, her song “Glow” becomes a scathing critique of the Black death gallery social media has become. This is especially true when she sings to her phone-addicted lover:

“All these suffering souls / that you cannot control / and you invite them all / in our bed? / Well what if I’m not big enough / to take in so much pain?”

Unlike “American Utopia,” which still builds its stage show entirely around Byrne singing lead vocals, the climax of “Octet” arrives when the entire cast defers to one person of color singing about their pain. It’s the song that’s haunted me the most, both because it’s frighteningly familiar to my own history of self-harm, and because it’s sung by a South Asian actress—two facts that are irreparably intertwined with each other. In the song “Beautiful,” Velma (Kuhoo Verma) describes her history of cutting. But she’s the one who also breaks the cycle of shame within the show, finding transcendent, if distant, connection to another woman similar to her through what sounds like Tumblr. The absurdity of the situation is not lost on her, but neither is the pain. Singing alone on the stage, she recounts:

“I stayed in my little room / singin’ my ugly tunes / tracing the lines hidden underneath my sleeves / hashtag cuts / a forest of dead trees.”

These lyrics conjure two horrifying images for me. I see slashes on my wrists, the blood underneath my olive skin weaving like tree bark; I also see a countless array of severed arms on a midnight blue website dashboard, moving upwards through an infinite scroll.

But the placement of Kuhoo Verma within this central role in “Octet” sends its own message. Yes, perhaps women of color like Velma are the characters in the show who are the most vulnerable, being both scrutinized by society and also dangerous to themselves. However, it’s because of this very fact that they’re the ones to initiate the process of self-healing, being able to name the horrors of the world, and find solidarity with other women through friendship or romance.

This is a role in America I so deeply want to have. Like Velma, I want to be the one to see through the chaotic veil of the everyday into some higher truth, the one whose pain becomes the thing that carries us out of the darkness. I want to find a connection where there was none before and have it blossom over my wounds.

But there are still wounds, and they are still deep. I still hesitate to embrace this role I’ve been cast in completely. Why is this person’s responsibility to feel the most pain in the show, to come the closest to self-imposed death? Must I suffer and sacrifice myself in order to save humanity? Malloy doesn’t place people of color in the utopian position of whiteness, instead chooses to have his South Asian character struggle with her pain and find a way out. But the conditions of this characters life—the institutions and histories that have led this woman to the brink of suicide—remain intact by the end of the show. Interpersonal connections may be discovered in the song “Beautiful,” but these empathetic coming-togethers of humanity cannot always solve the political chaos in which the characters of color in “Octet” find themselves.

The role of Velma as a savior figure within “Octet” is also complicated by the fact that her song is sung about another person, someone we never see on the stage. “Beautiful” might project the relationship between the two as the salvation within the show. However, I’ve arrived at a peculiar problem that has nothing to do with the way “Octet” is written, and everything to do with myself: whenever I imagine the beautiful woman that Velma sings to, that person has always been white. Whenever I imagine myself happy, connected together with friends and lovers, they have always been white. It’s as if through their whiteness, I can pull myself out of the brown quagmire of my being, as if surrounding myself with pale beauty will make everything feel pastel, light, and peaceful. Why did I imagine that a white man would deliver me from evil, and forgive all trespasses? Why did my dreams necessitate that it had to be a white man that would save me?

At 2 a.m. on Nov. 4, I was listening to “Beautiful” and watching election coverage. When I turned off the screen, I saw my reflection. I saw a person putting everything on the line for Joe Biden to save this country from its original sins and the never-ending nightmare of this pandemic.

Suddenly, the road to nowhere seemed to have a very clear end point.

/

Watching the 2020 election play out essentially came down to wondering how white people would decide my fate. No matter how much the Democratic Party opines about securing the Black vote (or how much they circle around now to discuss Asian, Latino, and indigenous votes), the fact that Joe Biden was the nominee reveals their true investment: securing the white, male, middle-aged vote.

Of course this election was about them. It’s always been about them. When has the world not revolved around their axis, the rest of us just forgotten planets orbiting their radiant, despicable glory?

“Even with exceptions, he, the white man, is always president,” writes Claudia Rankine’s gorgeous and hideous play “November,” which tackles this exact dilemma for people of color (a filmed version of the show is streamed on The Shed’s website from Nov. 1 through 7).

“Boss,” she continues. “My other boss. Husband, colleague, my seatmate, an accountant, lawyer, my waiter, oncologist, physical therapist, my murderer, my assassin. My my my my my my my. How could I not be invested in knowing him? We are inextricably tied together.”

“November” tracks Rankine’s cyclical journey of confusion, frustration, and sometimes connection with white men. It’s a journey she started tracking once she realized how often she was interacting with white men on airplanes, and they were given no choice but to reckon with her status as a Black woman.

Rankine’s writing has always been intertextual: her modern classic “Citizen” is a poetry collection that placed visual art alongside her writing to create a kaleidoscopic compilation of Black subjectivity within America. The fact that Claudia Rankine has turned to playwriting, staging the issues she’s invested in, is no accident. Rankine joins the ranks of playwrights like Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and Jackie Sibblies Drury as writers using the high-velocity confrontation of watching someone else in person to surprisingly express the anxious disassociation of being Black in this country.

While the absurd fantasy of “American Utopia,” and quiet moments of profundity in “Octet” could be abstracted through song, the majority of “November” is blunt, blistering direct address to camera. If the political import of the previous musicals were implied, the specific governmental and societal problems within “November” are explicit.

Most of the play unfolds as one long monologue, split up between five Black women actors credited as Narrators (Crystal Dickinson, who participated in Wesleyan’s event “The Ground on Which We(s) Stand(s),” is among these actors). The Narrators recount story after story of frustrating encounter, connecting this tapestry to the legacy of racism within America’s institutions. Meanwhile, intimately shot videos intersperse their dialogues: a Black woman surrounded by bright flowers, books strewn across a Central Park field, a Black woman shaving a white man’s scalp transforming him into a skinhead, Black men playing basketball and swimming in a pool. The mood created is one of complete exhaustion, and Rankine refuses to placate her audience with platitudes or qualifications. Rankine is writing towards both a denied subconscious and an embodied refusal to look away. Listening to the show is akin to hearing a polyrhythmic chant, meditative and disarming simultaneously.

Finding joy within this cacophony initially seems to be a moot point. Rankine’s work is clearly in conversation with Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe, Black scholars who have written extensively about the institutional and affective afterlives of slavery. But unlike Rankine’s previous playwriting, like the Afro-pessimism adjacent “The White Card,” “November” turns away from diagnosing problems to suggesting antidotes. The first of these is humor: many parts of the monologue take a turn towards stand-up comedy, eliciting a dark humor that inevitably recalls Richard Pryor and Whoopi Goldberg, but also the humorous poetry of Morgan Parker. The more decisive turn towards joy is at the end, in which the Narrators sing, dance, and discuss a new mode of being: the swerve.

“Being white is not fatal,” one of the Narrators speaks. “It’s the force and feel. It’s the emergency in feel. We feel in order to swerve. To swerve into the consciousness of another without the risk of losing the self. To swerve into the full potential of a whole self. A whole being. Human. That is the possibility.”

The play up until this point has been all about forced confrontations, externally mandated conversations, surveilled bodies. But Rankine asks us what it would be like if we felt our initial impulse as people of color (to run away from whiteness), and instead swerve wildly into the very thing that repels and controls us. Engagement with whiteness, and white men, might always be a fact of life. But what if we defined this engagement on our own terms, seeing dependence not as constricting but connecting? What if we could engage in dialogue like “November,” an exchange where two different parties can finally see each other for who we are? What might it look like for white Americans and people of color to talk to each other, for the first time, as equals?

For me, witnessing the end of “November” was like stumbling upon a field of lilies while traversing a desert: it was welcome, but also made me wary of some cruel mirage. Rankine’s suggestion of the “swerve” seems so ridiculous and yet so lovely at the same time. She must she’s aware of this fact. And still, she swerves into her historical oppressors anyway, hoping to find something new in a white fog of disappointment.

The presence of Asian Americans in the journey of “November” is a frustrating and beguiling one. One of the Narrators recalls an uncomfortable conversation she had with a white man on an airplane, in which the man implies that his son couldn’t get into an Ivy League school because of affirmative action. Seeing Rankine’s reaction, he then clarifies that it must have been Asians who took up his spot, not African Americans. During this testimony, there is a shot of an Asian woman staring into the camera, an uncredited role. It flickers, and then fades away. I couldn’t tell if this actress was in the rest of “November” at all.

Upon seeing this, I was confused. I know that Rankine has been an avid supporter of Hong’s “Minor Feelings.” Why then, would she choose to share the myth of the model minority, which scholar Michelle N. Huang states “has been wielded to position Asian Americans as a wedge within the field of black/white race relations in the United States,” without much commentary? I puzzled over why they would cast an actress in a role that is so fleeting, ephemeral, so as to almost not exist at all. It didn’t seem any different from the only role that Asian Americans have been handed to historically.

But I remember that the white actors cast in “November” occupy a similar position, playing unnamed characters who never speak, background players that the Narrators can move and position however they please. And then I remember that there are multiple Black people represented in the film who might not even be actors at all—their faces, their beauty, their lives are all just existing, without any set role to play. Even the five Narrators aren’t necessarily embodying characters, or even Rankine herself, as much as they are showing up on the stage as they really are. Saying that all of what Rankine has gone through—all of the shit that has gone down—could have just as easily happened to them in real life, without bright stage lights or an audience.

I had spent so long during election week waiting to see how my country would decide what my role could be. What part I would have to play on the national stage. But the more I think about “American Utopia,” “Octet,” and “November,” I don’t remember fictional characters as much as I do shattered reflections of real people, a communal chorus all singing the same lonely hymn. I’ve heard the word “divided” used over and over again this election season. A divided electoral college, a divided country, a divided family. While this might seem true on the surface, if you dig deeper like Byrne, Malloy, and Rankine have done, you see how united this country is. How bound we are to each other, how my freedom is tethered to so many lives outside my own, how my life is guided by the choices of a swarming community.

This whole time I had been seeking a role to play in America that would elevate me in privilege and status. The more radical move, as these playwrights point out, is the dissolution of any American cast(e) system all together. These plays might require us to all show up as ourselves not in any role at all. It doesn’t matter what role we’re playing, as long making room on the stage for everyone.

iv. coda / the empty stage

There are a few pieces of art I’ve found in the past few weeks that gesture towards this radical theatrical space of having no set roles, both of which feature the relationship between Black American and Asian American individuals.

The first is Quiara Alegria Hudes’s play “Water by the Spoonful” (which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2012). The play works as a sort of inverse of “Octet:” instead of having a therapy session in real life to talk about their addiction to the internet, a support group is formed over the internet to connect four struggling drug addicts from across the globe. One of the most poignant relationships is between two members named Chutes&Ladders (a 56 year-old African American named Clayton) and Orangutan (a 31 year-old Japanese American named Madeline). Both are loners who have sought the Internet to fill the gaps in their life. Clayton is estranged from his family, his son rejecting him any time he attempts to reconnect. Madeline (originally born Yoshiko) has traveled to Japan to finally discover her birth mother.

The banter between Chutes&Ladders and Orangutan online is clever, funny, and sometimes destructive. Clayton attempts to dissuade Orangutan from discovering her parents, fearing a relapse, leading to a heated debate. But what family doesn’t get into arguments like that? It’s clear that both Clayton and Madeline, feeling the absence of having a role to play in their family’s cast, have gone out and written a play for themselves, even if through the most unconventional way possible with a stranger on the other side of the globe. Madeline eventually can’t bear to see her birth mother. But she eagerly awaits to meet Clayton in real life, and so does he.

“It’s weird huh?” Madeline says when they finally hug.

“Totally weird,” Clayton responds. “The land of the living.” Through their connection, they have found a way to survive together, to surpass the dreaded Internet underworld into the light. There are no previous precedents for how this relationship will continue. Clayton and Madeline are not lovers, not related by blood, not just friends, not parent and daughter, but something else. They are creating new roles to play that exist beyond the bounds of the American cast(e) system.

This sort of queer family creation can also be seen in Bryan Washington’s new novel “Memorial,” released this year to much critical acclaim. The novel alternates narration between Benson and Mike, two lovers who, similar to Clayton and Madeline, attempt to navigate race and family in the midst of their strained relationship. Mike is a Japanese American chef, who discovers that his estranged father is dying; he quickly leaves for Osaka to create some sort of relationship with him before he passes away. Meanwhile, Benson is an Black daycare teacher living in the Third Ward of Houston, and must host Mike’s mother Mitsuko as she stays in his home.

The kinship created between gay son and estranged father, gay man and Asian mother-in-law, have rarely been seen before, and each member of these two relationships strain to find the proper way to act in roles that they could have never prepared for. But this sort of strange discovery was something that was foundational to Mike and Benson’s relationship at all. Even within the first few pages, there’s an aching sense of paranoia of being watched, of being on the stage of America playing something strange and nerve-racking (both cops and friends watch Mike and Benson together with unease). “Memorial” is the first book I’ve read to capture the delicate pain of being in an Asian-Black gay relationship, something I never thought I would see unless I wrote about my own experiences. But I’m so grateful someone else could write about these relationships with such care and attention, letting me know that what I felt wasn’t in isolation.

The lines that have stuck with me from the novel the most are the quiet moments between lovers, ones that didn’t have roles planned for them on the stage but learned to make a life for themselves in the shadows backstage. One comes early in the book when Benson recalls:

“A few months in, Mike said we could be whatever we wanted to be. Whatever that looked like. I’m so easy, he said. I’m not, I told him. You will be, he said. Just give me a little time.”

The fluidity of Mike and Benson’s relationship has no guidelines, no roles for them to easily fit into. There’s something painful about this, the way that these people have been erased from society, the sheer labor that Mike and Benson must do in order to imagine themselves as valid people on the national stage. But there’s something liberating about this situation, too. These queer of color subjects might have been forced to improvise lives for themselves, being given no role by society, but the sparks of imagination can flutter around the two.

Throughout the novel, Benson recounts all the times that he and his lover have said “I love you” to each other, moving backwards chronologically. One of the final pages of the novel reveals that the first time they said “I love you” to each other was not even in words, but through a shared experience moving through a quiet neighborhood together. What a gorgeous moment, to deviate from the rom-com screenplay or theatrical book you’re expected to follow in a relationship. What a terrifying freedom, going off script, creating a new role for yourself with the person you love.

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @nathanpugh_3

Leave a Reply