In “Cut Woman,” Dena Igusti and Ray Jordan Achan ‘19 Explore the Perils and Possibilities of Embodied Writing

Content Warning: This article contains references to female genital mutilation (FGM).

While watching a short performance film recently, we were struck by a surreal loop of actor and audience: the beginning of the film was a young person staring at a computer screen. Their red lipstick and red eyeliner accentuates a face that, despite being brown, appears waxen; exhausted and illuminated at the same time. They start reading off the computer:

“the grenade’s lung exhaled into our chests / and muslims have been spilled ever since / to be muslim is to always flow / from out of our fingertips…”

They continue, discussing the suffocating violence that accompanies having a Muslim identity, before abruptly shutting their computer and walking slowly to a mirror. In the midst of washing their face, they say this to their reflection:

“purplepink // mass // scabbing // on linoleum // somewhere // we live // on // with // out // nerve.”

Suddenly a long train of red tulle bursts forth from this person’s legs. It flows forth from their body, covering the bathroom tile, until the person starts bunching it up. The train leads back to the bedroom, where it is now draping across the ceiling and bed frame. It looks as if a river of blood has started circulating through the air, and the person looks on with both curiosity and fear. It’s clear that this room is their physical body, the recesses of their mind, containing memories, and their own story.

This is the evocative beginning of “Cut Woman,” a performance film directed by Ray Jordan Achan ’19, and written and performed by Dena Igusti. Premiering in Oct. 22 through the Prelude Festival NYC of 2020 (and now streaming online), the show follows Dena Igusti as they discuss their various identities: Indonesian, Muslim, queer, non-binary, and a survivor of female genital mulation (FGM).

“All procedures involving the removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons,” the End FGM Network website reads. “On average, girls are subjected to FGM between birth and age 15. GFM is not prescribed by any religion and has no health benefits. On the contrary the practice can cause life-lasting physical and psychological trauma.”

Igusti’s performance centers their own experience with FGM as the lens to explore mortality and grief within their culture, body, and personhood. “Cut Woman,” feeling both personal in its experiences but universal in its struggle and resistance to subjugation, is perhaps a perfect companion piece to the COVID-19 pandemic. The events of 2020 have transformed the American public’s understanding of our bodies’ relationship to communal, political, and interpersonal forces. “Cut Woman” stands at this reckoning, reminding readers that people who inhabit bodies like Igusti’s have been dealing with these forces their entire life.

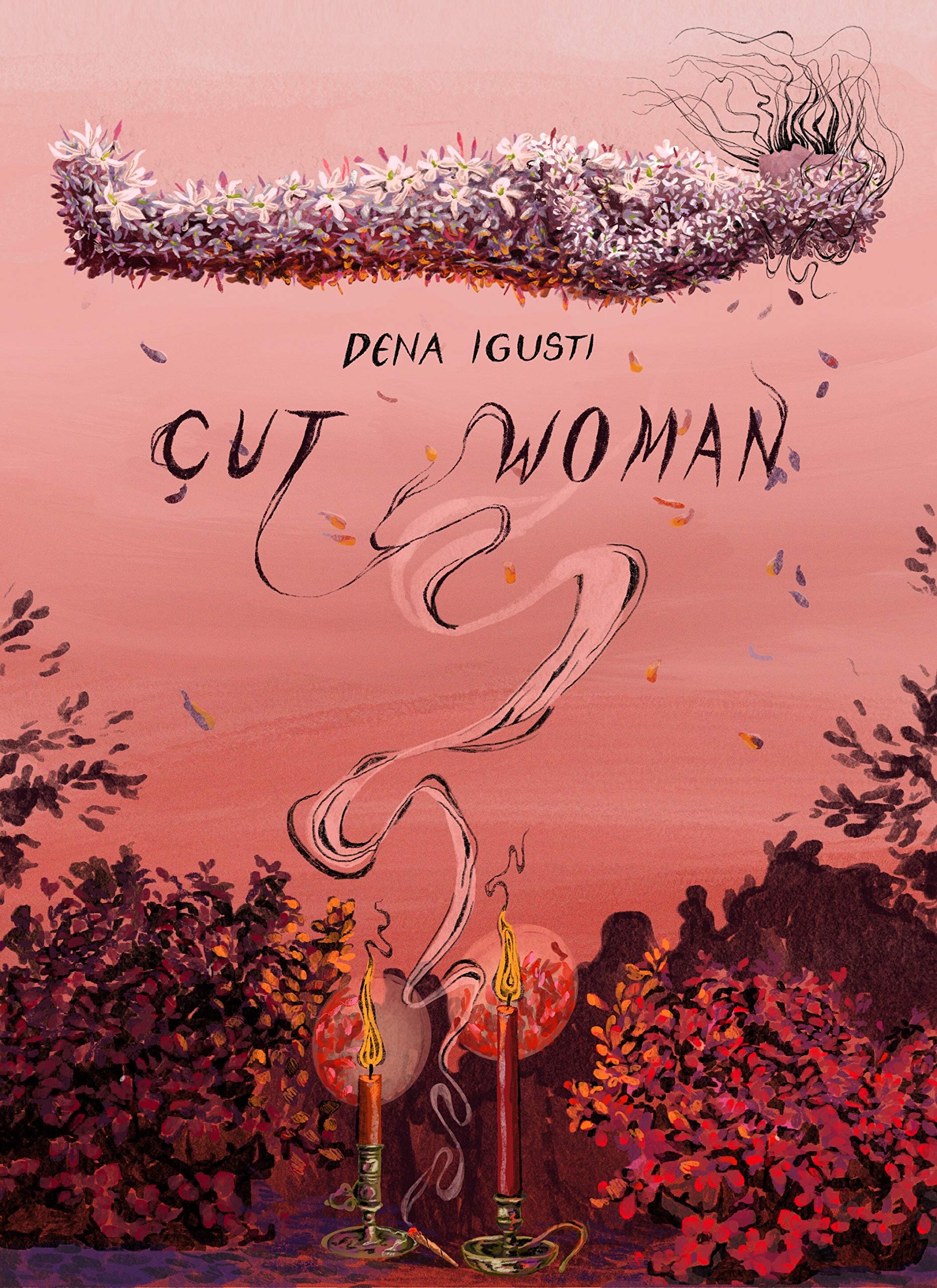

“Cut Woman” began not originally as a performance piece, but as a collection of poetry written by Igusti that was published by Game Over Books earlier this year. The slim yet powerful poetry book titled “Cut Woman” chronicles their life. The collection consists of 26 poems ranging in form from free verse to erasure, a form of found poetry. Through them, Igusti takes readers on a deeply emotional journey exploring dissociation and loss.

The book starts off with a poem about Muslim identity, and then shifts to work recounting Igusti’s experience with FGM, which occurred when she was nine years old. In the poem, “after the incision,” Igusti details how her body seemed to separate from her.

“the body leaps across the atlantic // i try to pull it down by the ankles but its legs take me with it.”

The speaker then goes on to have a conversation with their own body, imploring it to return to them. When they ask the body why it won’t come back, the body scoffs in response. But later in the dialogue, the body accuses Igusti of letting the FGM happen.

“Do not be surprised that the rest of me left too,” the body says.

Another poem, “sunat: a recollection (in the wake),” is written like a script with stage directions. It features Igusti and their body (now named Body) having another discussion, only this one is set 10 years post-FGM. Here, Igusti is trying to rekindle their relationship with Body, but Body resists those overtures; it still feels estranged and still holds a lot of anger toward the speaker. Early in the collection, Igusti establishes a theme of dissociation from their body. Igusti revisits this topic in several other poems, including “portrait of my reflection on a blank computer screen (after ocean vuong),” where they use the concept of one way mirrors to express such feelings of detachment from their body.

“it’s a one way mirror // someone on the other side is watching you // how i must love myself through // another’s eyes // how the closest to myself i can be // is through another view.”

In an interview with The Argus, Igusti was honest about how the disassociation from their body is a lasting effect of FGM.

“I felt as though I let my body down and in turn, I thought my body let me down,” Igusti said.

Another way Igusti conveys these feelings of internal shame and responsibility in the book is by repeating the phrase “body suspended in memory” in multiple poems within the collection. When asked about the significance of the phrase, Igusti explained that the separation that they feel from their body stemmed from one specific memory. This is why they view their body as a before and after. Furthermore, their body almost feels stuck within the memory of the trauma.

“What does it mean to constantly live in retrospect?” Igusti asked. “And what does it mean to constantly live with the after images of [trauma]?”

In addition to dissociation, Igusti spoke about their home life and dealing with loss within their community. Igusti has always lived in Queens, New York. Gentrification in the area has led to increased housing instability and a lot of people in their community, including their family, being evicted. What followed was a period of death, loss and grief.

“It would be like ‘Hey, you know this person got kicked out by their landlord and I haven’t heard from them since, I don’t know where they are,’ or ‘What? You didn’t know? This person died,’” Igusti said.

Igusti detailed how they wanted to incorporate these two main themes, both living with the detachment from their body and also coping with the losses in their community, into the “Cut Woman” collection. They also mentioned how they were walking the fine line of displaying everything that had happened to them while also not misrepresenting the people in her life and her heritage.

“First I had to understand what was happening with me and why does [FGM] happen,” they stated.“And the role of motherhood, the role of matriarchy, the role of patriarchy. What does it mean to live in a body that is inherently not trusted? And also at the same time, I had to write about it in a way where I’m not demonizing my people and demonizing my culture, and I’m not demonizing my religion either.”

Initially, Igusti didn’t write with the intention of creating a full collection. They wrote most of the individual poems in 2016 and 2017 when they were around a year into college. As they shared these poems with people in their community and began to publish some of them on the Internet, it dawned on them that all of the poems had a similar theme and would work well together in a collection. Once they had decided to pursue creating this book of poetry, they began to think about the placement of each poem within the book. At first, they organized them in chronological order starting from the FGM procedure to the times where they were experiencing constant losses within their community. However, their publisher suggested that this wasn’t the best order and that it didn’t tell their story, it just organized the story by time. Igusti then re-evaluated and came up with a new order.

“I started with focusing on the loss of myself, then losses that weren’t necessarily related to death but also still have to do with death, and then navigating being exposed to death in different ways,” they said.

The idea to turn the poetry collection into a performance was germinating even before the poetry collection was released, stated director Ray Jordan Achan. Achan and Igusti had met during high school, bonding over their shared experience of being people of color going through an underprivileged New York school; they also started their school’s drama club. The two reconnected after college when Achan directed “Sharum” at The Players Theatre, a documentary theater piece about a Muslim family that Igusti had co-written. It marked Igusti and Achan’s debut work off-Broadway, and the duo have been collaborating more frequently ever since.

Despite being the year that most theater has been cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 was also the year that Achan founded his theater company Exiled Tongues, a collective with the intention of supporting artists of color. Achan founded the company along with Igusti and Arline Pierre-Louis ’19. Together, the group has been busy both applying to theater relief grants (Achan received the pet project grant by playwright Jeremy O. Harris with Bushwick Starr), as well as providing artist in residency microgrants of their own for artists in need. Achan hopes that Exiled Tongues only continues to grow after this.

“I hope that after COVID I’m able to do way more, do actual shows in person, and I’m interested in the digital space too but I don’t know where to go with that, and that’s something as an artist that I’m figuring out too,” Achan said in an interview with The Argus. “But I realize that people need money right now. I don’t have a lot of money right now, but whatever money that I do have I’m interested in giving it back to the people who need it the most.”

After working with Igusti to produce an adaptation of “Cut Woman” through their company and with the Prelude Festival, they were approved and had to work quickly to produce their show within under a week. The duo both rose to the challenge, Achan being used to working under a crunch.

“There’s something awesome about having a small amount of time to work on a project, because you realize what’s important and what needs to get done now and what can wait until later,” Achan said. “I realize that it wasn’t the most perfect performance piece, but it accomplished what we wanted to do visually, and that was the most important part.”

What brings Igusti’s lyrical poetry to life in the film is the intense imagery, from the continued use of the red tulle, to the looking glass quality of constant reflection, to even the use of multiple Instagram filters on Igusti’s face as a means to comment on how femme-presenting bodies are disseminated over social media. This was one of the first film projects that Igusti has done, and going into it, they were excited about representing their story with visual components. However, they grappled with emphasizing either the subtlety and obviousness of the props being used.

“There were things I thought of in the beginning which were way too literal to the point that they were just graphic,” Igusti said.

One example of this was the use of medical gauze, an idea Igusti told us was discarded because they felt like it was way too literal. They ended up using red tulle throughout the film to represent various concepts related to the body. Igusti also wanted to focus on displaying the visualization of the separation of their body within a shared space.

“It constantly feels like being two separate entities but we are always here in the same spaces all the time and sometimes it’s awkward and a lot of times it’s painful,” they said.

In the beginning of the interview, Igusti spoke about their involvement in slam poetry. However, during the competitions, they said that they would trigger themselves into reliving their trauma on stage in full view of an audience. Igusti soon realized that this was not healthy way to continue performing.

“I had to go into it knowing that I wasn’t trying to relive trauma and get some pity points,” they said. “I did want to write with the interrogation of not only the process of it and the actual raw feelings of disconnection from my body, but also how it’s received in the media.”

Igusti wants people to understand and empathize the trauma that they have gone through without feeling sorry for them. This is reflected in the “Cut Woman” performance film, which despite containing imagery related to bodily harm and death, is centered on Igusti’s resilience. The end of the performance is a hopeful note, speaking in solidarity with the audience.

“i love me you us them / before i you we they / go to bed / i wanna know your / favorite flower / just in case,” Igusti writes.

As Igusti speaks these lines, they rip up the long red train of gauze into smaller pieces, an act of destruction that somehow still feels creative, a chorus of tattered fragments surrounding them just like their poetry. These fragments are a part of Igusti, and extracted from their body, the red pieces held tenuously by Igusti between the audience and themselves.

The level of vulnerability that Igusti exhibited onscreen is not lost on Achan, who made sure to prepare heavily for the emotional care required for his directing role.

“All that time I was talking to Dena, we were having these conversations about their personal experiences, about what other people in their position are going through, it requires so much love, compassion, care, and coming from a place of genuine care for the person,” Achan stated.

He additionally wanted to explain that he didn’t want the audience or himself to feel manipulative when engaging with Igusti’s performance.

“I feel the need to say this: you don’t use your art to exploit a situation or your trauma,” Achan said. “This art is not about exploiting trauma, it’s about just showcasing it and you know this is what we can talk about. And that’s an approach that I take with everything I direct. Just so much love, so much care, and so much conversation with whatever we’re talking about.”

Ultimately, the heartfelt collaboration of Igusti and Achan–two queer people of color, both theater artists in New York City–is what viewers walk away remembering. Achan himself stated that he hoped audiences would come away with a greater level of understanding.

“I think people should just understand the amount of care that queer people of color have to go through. It is not easy, especially when so much of the world’s trauma weighs on you, and imagine just carrying that. I don’t even know how to express that. How do you carry all that trauma and still live in the world and still be a functional being?”

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @nathanpugh_3

Sabrina Ladiwala can be reached at sladiwala@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply