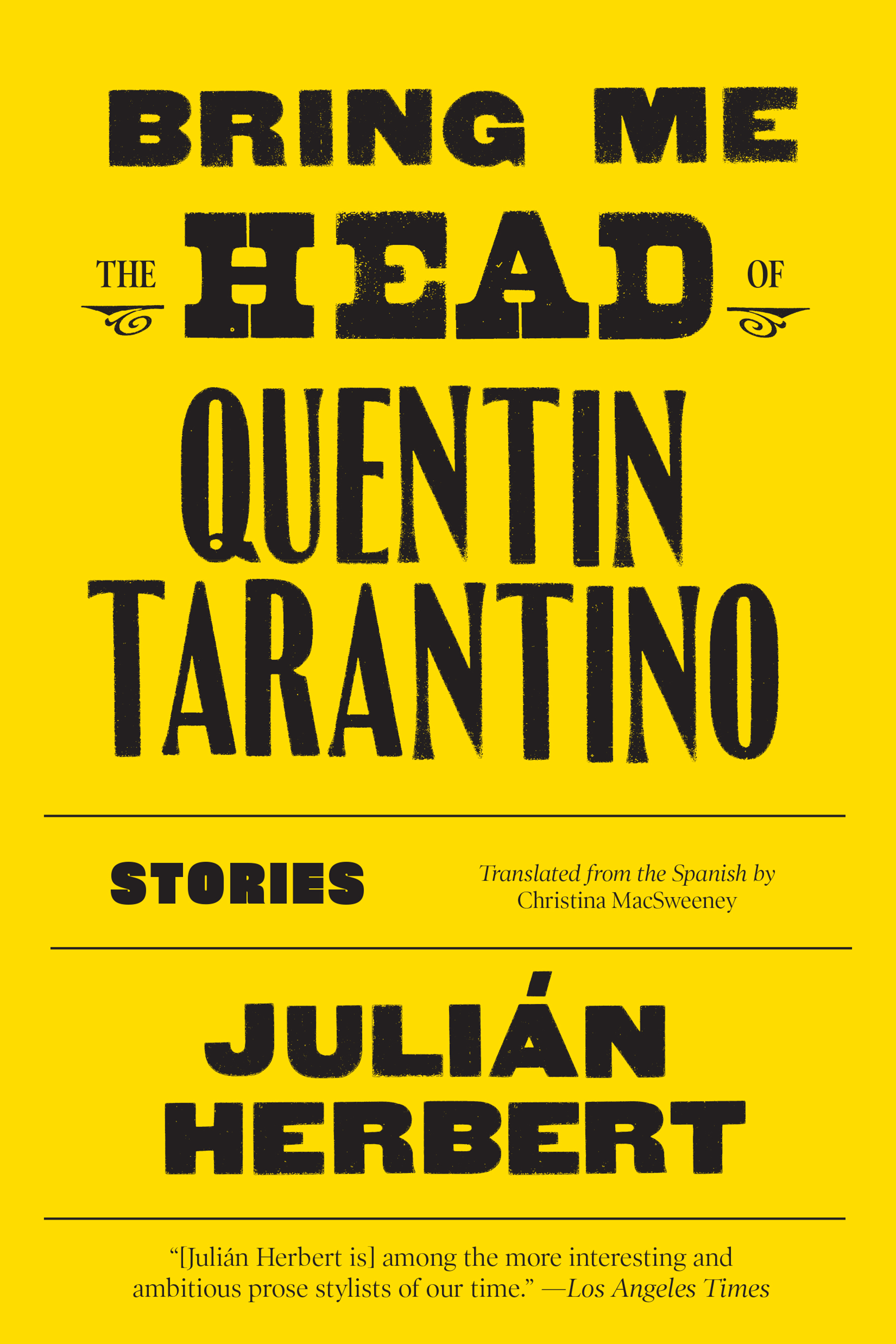

On Nov. 3, the short story collection “Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino” by Juliàn Herbert was published for the first time in English. The collection was translated by Christina MacSweeny, following its initial publication in Spanish in 2017. It’s a startling and frenzied collection, featuring stories that range from an artist who finds sheet music inside his teeth, to another artist who films himself having sex with HIV-positive women in search of utmost obscenity, to a notorious drug lord who looks exactly like Quentin Tarantino.

Herbert’s prose is consistently beautiful, and more often than not, I found myself pausing while reading his stories to take in the profundity of their meanings. In fact, he doesn’t only begin and end the collection’s first story with the one of his most curious lines, but also ends the last story—the title story—with this exact same line:

“Don’t fool yourself,” or, depending on the story, “Stop kidding yourself: that thing you call ‘human experience’ is just a massacre of onion layers.”

In both the beginning and ending story, this sentence is used as a tool of metafiction. In the collection’s first story, “The Ballad of Mother Teresa of Calcutta,” Herbert’s narrator tells us that this alimentary massacre is something that writers, in particular, can’t escape. The writer’s challenge is to find the least-damaged layer in each of their characters.

In this story, the narrator tells us about his friend Max, who has been accused of hiding illegal weapons for the Nicaraguan government. While in the airport trying to get to Mexico, Max meets Mother Teresa and proceeds to vomit all over her. If this sounds implausible, that’s because it is. As we find out throughout the course of the story, Max has made a mistake in dealing with the narrator, who is not any arbitrary voice, but rather a paid “memory coach,” that is, a person whom clients pay to take facts about their lives and spin them into compelling memoirs of self-importance. The narrator can deal with his clients’ assumptions that these stories are their own, but for him this is a strictly monetary business, so he gets to do something different with Max’s unbelievable tale:

“I rolled out this experimental payment strategy: hijacking the memories and anecdotes of certain clients and offering them as short stories–in exchange for a modest sum–to cultural publications and literary supplements.”

If this narrator’s framework is correct and memories make up stories, then Herbert’s first hijacked story is a precursor to the rest of the collection. Stories as bizarre and grotesque as his should not be beautiful, but line after line proves that logic wrong. Sure, the big event of this story is that Max throws up all over Mother Teresa, but it’s a story that is really about what drives the need for telling stories, and furthermore, one that asks important questions about the memoir genre, which has become increasingly popular in the past 50 years.

Herbert’s short story “White Paper” is as close as the collection gets to science fiction, and it is really half-story, half philosophical-scenario. It’s told by a first-person plural narrator, a group of medical forensic assistants trapped in a house where blood spatters covering all the walls have been replaced with ambiguous white stains. Though they share the same job, the assistants don’t know one another. The house is surrounded by loud, penetrating music that prevents them from going outdoors. Trapped inside a house blanketed in whiteness and surrounded by music that changes into a new sound of horror every day, they wonder if they are dead or going crazy.

“The one indication that we might be dead is our recognition that we are on the verge of insanity: madness is the nearest thing to being a ghost,” Herbert writes.

The narrators even contend that being ghosts would be easier, because they could be just like the white substance itself and exist without having to suffer. After seeing a tree branch slice an old man in half outside of the house, they decide that:

“Destroying the residence is the only viable strategy for halting the degradation of its evidence. Lacking a preconceived plan, we simply exploited the situation as we found it: we snorted the powder in the kitchen, scarred the floors with spinning-top tournaments, devoured the whitewash on the walls…”

The characters consume just as much as they destroy in this house until this consumption and destruction becomes their daily ritual; they confine themselves to the house until there is no more house to be ingested. The structure of the story is told in five parts, reminiscent of the structure to a musical composition. And like the dangerous, seductive music that swells outside the house, the lyricism of this story works to convince the reader that the inside of the house is beautiful and safe. It appears even more beautiful in these ending passages of destruction, as the narrators’ enactment of control manifests in a visual sequence of their losing it, tearing everything around them to shreds.

Less of an immersive, deceptive beauty, and more of a shockingly-profound commentary on the self-indulgence of contemporary art, the short story “NEETS” (an acronym for Not in Education, Employment, or Training) may very well be Herbert at his most bizarre. This is where we meet one of the collection’s conceptual artists, a man who has sex with HIV-positive women to make extremely successful porn. After all, as the narrator tells us in the first paragraph, he’s had his work exhibited in five international biennials.

Through the course of the story, we learn that the man is living with Vinaey, one of the women featured in his porn. She’s gotten pregnant, though he swears that he doesn’t know how. He had gotten tested upon finding out about her pregnancy and he tested negative for HIV, a fact which:

“…isolates me from [Vianey and the baby]…I lie awake at night thinking that my need to observe and my loved one’s suffering will soon give birth to Death: not simply a sick human being but an entity that destroys everything it touches.”

For all of his depravity, or perhaps because of it, this narrator is extremely frank with his thoughts. Within this perspective, however, we are let into a thought about how the narrator really feels: he desires the suffering that Vinaey feels and that his child will likely inherit in some form of immunodeficiency, both because his perversity has now excluded him from a defining feature shared between mother and child, and also because he has gone to every possible extreme to physically embody and join himself to this disease.

Herbert’s stories are most effective in these inconclusive moments, where in the often absurd longings and desires that begin hidden in conversation with the self become too real and independent to be kept secret. As each obscene desire bursts from a place of repression, the author peels back another layer of the onion, exposing something which though unbelievable, gets at something true.

Chiara Naomi Kaufman can be reached at ckaufman@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply