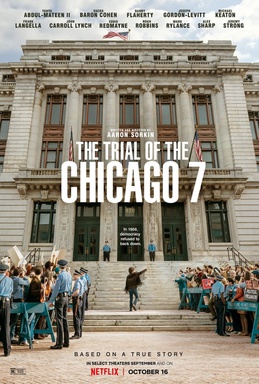

“The Trial of the Chicago 7”: A Period Piece For the Current Moment

An increasingly unpopular president faced with civil unrest. A contentious election on the horizon. Mass protests met with police brutality. This is where writer and director Aaron Sorkin’s new film “The Trial of the Chicago 7” begins, in the summer of 1968. But, in many ways, this could describe the year that we have experienced so far. While the events depicted in the film take place five decades ago, “The Trial of the Chicago 7” speaks strongly to the present day, painting a picture of the struggle for change in the face of a hostile system.

In August 1968, a wide array of anti-war activists took to the streets of Chicago during the Democratic National Convention (DNC) to oppose president Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. The protests attracted massive crowds, and eventually they descended into violence.

A year later, with Richard Nixon as the newly elected president, the commander-in-chief’s first order of business was to crack down on dissent. Johnson’s Attorney General Ramsey Clark (Michael Keaton) deemed that the DNC protest violence was a police riot instigated by the Chicago Police Department and Illinois National Guard. By contrast, Nixon’s Attorney General John N. Mitchell (John Doman) blamed the protesters, and prepared to press charges for conspiracy and inciting a riot.

The film follows the heated court case tied to the event. The faces of the government are prosecutor Richard Schultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Judge Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella). Across the courtroom from them sit the titular defendants: Students for a Democratic Society leaders Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) and Rennie Davis (Alex Sharp); founders of the Youth International Party (better known as the Yippies) Abbie Hoffman (no relation to Judge Julius Hoffman, Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong); National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam leader David Dellinger (John Carrol Lynch); as well as Lee Weiner (Noah Robbins) and John Froines (Daniel Flaherty), two less prominent activists designed to give the jury someone to acquit.

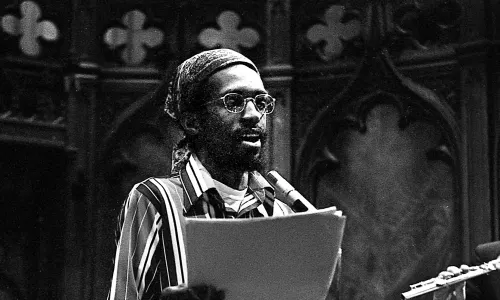

Black Panther Party Chairman Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is initially an eighth defendant, but his case is later severed from that of the other seven. Although the defendants hardly know each other, and have little in common other than their broadly left-wing politics and Chicago locations, Judge Hoffman has already made up his mind on their guilt. In his eyes, these eight men are menaces to society, and are to be treated with nothing but contempt.

It doesn’t help their case that the defendants themselves don’t get along particularly well. Central to the film is the dynamic between Abbie Hoffman and Hayden. Abbie Hoffman, as portrayed by the chameleon-esque Baron Cohen, is gleefully anti-authority, delivering his politics like standup comedy and staging theatrical stunts that get the Yippies’ attention, but, in Hayden’s mind, don’t accomplish anything for the issues they care about.

While Hayden shares Hoffman’s goals, he is far more comfortable working within the system to effect change. Hayden states that he probably wouldn’t have protested had a more anti-war candidate been nominated at the DNC. Later in life, he would go on to spend decades as a member of the California State Assembly and Senate.

These arguments still resonate today, as activists in cities and on campuses across the country struggle with how best to pursue change on issues ranging from Black Lives Matter to climate change. Arguments over which tactics are most useful or productive can be hashed out endlessly.

Sorkin is known for his tendency to write fast-paced, hyper-literate dialogue. A courtroom setting is a playground for him, giving him many opportunities to indulge in eloquent grandstanding and snappy retorts. The legal drama is also where Sorkin’s roots lie; his first screenplay in 1992 “A Few Good Men,” adapted from a play he had written, is also in this genre of film. He even returned to the courtroom in his theatrical adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird” which premiered on Broadway.

Surprisingly, the screenplay of “The Trial of the Chicago 7” is less typically Sorkin-esque than one would expect. Dialogue flows naturally as much of it is taken directly from the real trial’s court transcripts. There are only a few notable exchanges which exemplify Sorkin’s signature style that some viewers love, and others love to hate.

Another staple of Sorkin’s style, as shown in works like 1995’s “The American President” and “The West Wing,” which ran from 1999 to 2006, is the focus on patriotism and faith in American institutions. But in “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” he wisely restrains this instinct. The striking imagery from the film is less flag waving in the wind, more police hiding their badges and beating protestors, with blood and tear gas in the air.

From the start of the film, Sorkin dispenses with much of his trust that the American judicial system could function fairly. For example, when Seale continually complains that he has been denied counsel (the trial moved ahead despite Seale’s lawyer requesting a delay for him to undergo gallbladder surgery), Judge Hoffman has him gagged and shackled to his chair, an offense so egregious that the prosecution requests Seale’s case be declared a mistrial.

It’s not a spoiler to say that justice is not achieved in “The Trial of the Chicago 7,”. But the film’s eight defendants achieve a moral victory in the face of an unmovable system. It’s an atypical outing for Sorkin, and although he occasionally slips into sentimentalism, the overall experience is more immediate. As we witness the violence of the 1968 DNC protests, interspersed as flashbacks throughout the trial proceedings, we are reminded of what it takes to stand up against injustice, and the power of activism, in its many forms.

“The Trial of the Chicago 7” is now available to stream on Netflix.

Oscar Kim Bauman can be reached at obauman@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply