Now that the semester is in full swing, it can be hard to find time to read for fun. But in a pandemic that limits our travel to unfamiliar places and contact with strangers, books can provide some rare adventure and a much-needed reprieve from the blue light of our communication devices. If you’re mourning chaotic college nights, or if you’re just craving excitement and novelty in general, consider curling up with one of these new releases. Remember to support local bookstores, too! Whether you are looking for something to help you understand current events in a new light or are looking for some comforting escapism, The Argus Arts and Culture section has you covered with our flash book reviews.

c/o amazon.com

“Thin Places: Essays from In Between”

By Jordan Kisner

A proverb in Celtic mythology claims that we are always about three feet from the invisible world: the realm of spirits, of possibilities, of the divine. Yet, in this proverb, there are some moments and places, called “thin places,” in which the veil between this world and the invisible world diminishes, in which we cross a threshold that we previously believed impenetrable and come into contact with something beyond our ideas and ourselves.

In Kisner’s debut collection, “Thin Places: Essays from In Between,” thin places often occur where relatability can be found in the extraordinary. Such is the case at the extravagant colonial debutante ball on the Texas-Mexican border, where young girls dress up like Martha Washington, or in the symmetrical neighborhoods of Shaker communities, where worshippers forsake all desire and show reverence to God through embodied trembling and geometrical dances. Yet in other essays throughout the collection, thin places emerge when a hint of something otherworldly sneaks into the ordinary, such as in the theoretically immortal rhizome of an aspen grove, in the stories our bodies tell after we die, or in the common yet rapturous feeling of falling in love. The pieces in Kisner’s collection do not pull back the veil on experiences of awe, terror, love, and belief as much as they write from within the veil itself, occupying the space between the internal and external with contagious curiosity and enthralling insight.

It is perhaps the recent absence of strangers in my life which has drawn me more than usual to reportorial essay collections, as well as the satisfaction of being able to finish reading a cohesive piece of writing in my short breaks between academic obligations. Reading Kisner’s collection, however, did not only fulfill my desire to reach outside of my own experience, but also compelled me to delve inward and find some grounding in the “thin place” that accompanies the current upheaval of the pandemic. Always engaging with the ineffable, Kisner’s essays demonstrate a way of believing in the world which, though devoid of gullibility, pulses with both empathy and wonder.

— Sara McCrea, Arts & Culture Editor

c/o newyorker.com

By Abdellah Taïa, translated into English from French by Emma Ramadan.

Before I went to college, one of my parents told me that I better have a female roommate. When I tried to explain the nuances of the situation—that a person’s gender does not necessarily align with their biological sex—I heard laughter. My parents, like so many people in America, still have a resistance to discussing any kind of queer identity. To them, it’s just another delusion or trend, and not a definitive part of the way people live.

But queerness lives as it is lived—with fullness, harshness, trauma, and resistance—in “A Country for Dying,” Taïa’s latest novel. There is no space for pleasantries in this text, and certainly, no time to entertain neoliberal fantasies about perseverance in the face of an oh-so-overly-complicated spectrum of identities. In a slim 136 pages, this novel is unapologetic.

“A Country for Dying” traces the intertwined lives of Zahira and Zannouba (dead name: Aziz), Morrocan prostitutes in Paris who share the kind of friends whose bond refuses to retract. At the beginning of the text, Zannouba prepares for gender reassignment surgery, and though Zahira’s femininity is the type of womanhood she aspires to embody, Zannouba needs Zahira most when her understanding of her friend is as real and honest as Zannouba’s trauma:

“Zahira understands that I don’t want people to call me right now,” Zannouba narrates. “There’s nothing to say. The operation happened. I changed my sex…In me, in its place, there is an opening. But I feel nothing. Nothing…nothing.”

It is in the style of the prose where I personally felt most uncertain. Sentence fragments and direct, indicative statements take precedence over longer moments of language that would more conventionally convey the complex interior feelings and lives of characters. But Taïa avoids sentimentality by avoiding embellishment. Interestingly, the lyrical grace that this novel refuses to offer is perhaps what Zannouba most desires:

“I want a first name like [Zahira]. It sounds so good…A little flower…The orange blossom. [Zahira is] the heart.”

The novel’s writing style encourages the reader to engage with the text not on their own terms, but on the narrator’s; in other words, the author’s style itself is part of the author’s message. In “A Country for Dying,” there may be beauty, but it is an unforgiving beauty that does not soften or shy away from the realities of the queer experience. Positive, legible representation of queer and trans subjects isn’t always the best. There are some conversations that are not meant to be easily digestible for everyone, Taïa’s seems to tell us. Zannouba’s lived experience is not so easily universal nor clear just because it exists in the literature.

– Chiara Naomi Kaufman, Contributing Writer

c/o amazon.com

“Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass”

By Lana Del Rey

Lana Del Rey’s new poetry book, “Violet Bent Backwards Over The Grass,” is an intimate look into the singer’s psyche, full of aesthetically pleasing imagery and lines that would make killer Instagram captions.

To fans of Del Rey’s music, this collection will mark a clear turning point in the way she presents herself to her audience. When Del Rey first gained popularity, she was criticized for the themes of feminine submissiveness she perpetuated in her music, at a time when her female contemporaries were attempting to empower women with their music. However, while the traditional views of women aren’t entirely abandoned in this collection, as the poems progress, you can see her journey towards independence. Like a lot of music today, Lana’s music is usually about her romantic relationships (however toxic they maybe), but in her book, she also includes descriptions about less tangible relationships that have encouraged her to have more agency. Her poem “L.A Who Am I To Love You,” a love letter to Los Angeles reminiscent of the Red Hot Chilli Pepper’s “Under the Bridge,” portrays Del Rey’s shift in priorities as she seeks approval only from the city she calls home.

For her first published work—and hopefully not her last—the collection is remarkably original. It isn’t just a book of lyrics without a melody, like what may be expected from a singer/songwriter; she experiments with free verse and doesn’t rely on a typical rhyme scheme to drive the rhythm of each piece. The format is interesting, and like everything, Lana produces, vulnerable. Her notes (and teardrops) in the margins, as well as the inclusion of multiple drafts of some of the poems, give the reader insight into her creative process and let the audience feel like we are reading her personal journal. It’s a quick read, but it begs to be savored and reread, offering valuable insight on relatable issues.

— Molly Meyer, Contributing Writer

c/o amazon.com

By Zadie Smith

When you were forced to quarantine this March, what did you do? The responses I received from my friends during this time were varied: some were learning how to bake bread, others were forced to move out of their homes, others were left staring into the void. Regardless of your identity, many of us were forced to find something to do.

For the acclaimed writer, Zadie Smith, this “something to do” was writing “Intimations,” a short collection of six essays recounting her time in the first few months of the pandemic, as the world shut down. In one essay, she recounts all the conversations she’s had with her friends and remarks:

“I do feel comforted to discover I’m not the only person on earth who has no idea what life is for, nor what is to be done with all this time aside from filling it.”

That statement is a great encapsulation for the contradictions of Smith’s book: she simultaneously rejects her position as someone with authority, and yet theorizes about the state of the world anyway. Many of these essays offer insightful observations. “Peonies” discusses her submission to nature as it relates to both COVID-19, her gender, and her mortality. In her last essay, “Postscript: Contempt as a Virus,” she deftly connects the murder of George Floyd to a history of white supremacy through the metaphor of a virus.

The virus metaphor seems to surpass timeliness. Along with Jeremy O. Harris and Isabel Wilkerson, Smith and other Black writers are finally turning the racist biological language so often used against them into their own ontology for discovery.

Some essays don’t have new ways of looking at the world as much as they are examples of beautiful examples of prose. In “American Exceptionalism” Smith doesn’t say anything I didn’t already know about America, but revisits valid criticisms through a Black British lens of disappointment. In “An Elder at the 98 Bus Stop” she recounts a self-debasing piece of protest art by an Asian American man, but fails to engage with the protest in the context of Asian American life, nor with the originality of Cathy Park Hong’s recent essay collection “Minor Feelings.”

“Intimations,” more than anything, functions as a snapshot of our current time period. The fact that Smith gets to be the one to write this snapshot speaks to her elevated place in the literary canon, but also of class privilege she doesn’t always engage with. When the world went into lockdown, she got to write while others went to work considered “essential.” Even though she sometimes denotes these double standards, the only true example Smith gives of how to deal with the present moment is her own writing.

“Intimations,” whether intentionally or not, doesn’t leave you feeling safe, satisfied, or whole. But then again, nothing does these days.

— Nathan Pugh, Arts & Culture Editor

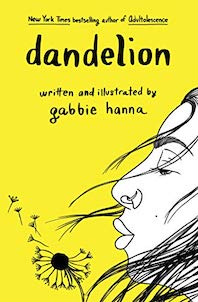

c/o amazon.com

By Gabbie Hanna

“Dandelion” is Youtuber and social media influencer Gabbie Hanna’s second book of poetry. Much like her first one, it focuses on her experience in navigating the world of fame, as well as her experiences with trauma. Some poems are more obvious in their effort to appear witty or deep, which ultimately comes across as contrived and cliché. Other pieces, however, are personal and approachable, brushing up against something remarkably thoughtful.

Throughout her work, Hanna finds her way out of traumatic and unhealthy relationships, yet struggles to define herself and find strength as an independent being. Reading her book almost feels like you’re reading the poetry of a friend: it’s earnest and honest, with an unguarded tone. After reading an entire book that’s almost exclusively and relentlessly about the author, though, this tone can start to seem self-centered and self-aggrandizing.

An example of this lies in the final poem, “Tragedy.”

“[M]y artistry is erecting shrines in honor of the things that / destroyed me,” Hanna writes, “I don’t know how to write about anything but pain.”

This is not a profound insight, but a redundant one. Her obsession with emotional pain is a fairly obvious theme of the book, so her need to explicitly state it in the last few pages just feels like an excuse to romanticize it.

There’s certainly something to be said for the feeling of connection and intimacy Hanna’s hyperfocus on herself creates, though it doesn’t make for a masterful work of literature. If ever there was a time for accepting art in all its forms and all its voices, it is now, during this pandemic in which so many of us have expressed ourselves through messy, unprofessional, perhaps not even good art, but art which is deeply felt and needed nonetheless. I, myself, am not a fan nor a follower of Hanna’s life or her online presence, and so this book is a bit wasted on me. But that’s fine; I am not the intended audience. The nature of influencer poetry is not that it will attract new fans, but that it will give people who already love Gabbie Hanna new, exciting glimpses into her thoughts and her life. Surely there is room enough in this world for books of poetry that don’t feel the need to accomplish anything more than that.

— Ella Tierney, Contributing Writer

Sarah McCrea can be reached at smccrea@wesleyan.edu

Chiara Naomi Kaufman can be reached at cnkaufman@wesleyan.edu

Molly Meyer can be reached at mkmeyer@wesleyan.edu

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu

Ella Tierney can be reached at etierney@wesleyan.edu