Bury is a town of about 80,000 people in Greater Manchester, England. Its football club and dominant cultural institution, Bury F.C., was founded in 1885. In 2019, after years of financial scrambling, the club found itself roughly $6.2 million in debt. Club ownership was unable to demonstrate their ability to pay or find investors to shoulder the burden. At the dawn of the 2019-2020 season, Bury was expelled from the English Football League. Fans have not seen their team play since and no solution is forthcoming.

The same summer Bury was expelled, Manchester United, just eight miles south of Bury, spent $236.25 million signing new players. Manchester City spent $183.5 million.

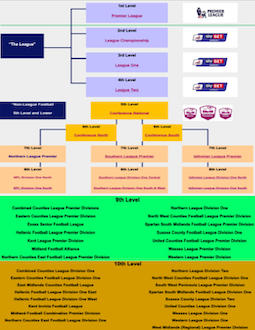

c/o myfootballfacts.com

Soccer leagues in England (a handful of clubs are based in Wales, too) are structured in a tiered system. The Premier League (PL) is top, followed by the Championship, League One, and League Two. The several levels below League Two form a pyramid, becoming increasingly local and semi-professional. Clubs can move up and down these tiers based on performance in dual processes called “promotion” and “relegation.” Bury had just been promoted from League Two to League One at the time of their expulsion.

Sports, more than we sometimes realize, mirror the societies in which they exist. Money is concentrated at the top of English football. The greatest source of income disparity: TV rights deals. Between TV and prize money alone, a PL club can expect to rake-in about $170 million more annually than a Championship club. Only a tiny fraction of Premier League TV money filters down. Clubs in lower tiers are thus more reliant on ticket and stadium food and merchandise sales than PL clubs. Most clubs in the Championship and League One regularly take annual losses in the millions.

When the pandemic hit, a worrying situation turned dire. If not for Britain’s version of the Paycheck Protection Program, some lower league clubs would have followed Bury into oblivion. It is still a long haul ahead with empty stadiums.

This ever-worsening threat foregrounds the biggest soccer story this week, first reported by Sam Wallace of The Daily Telegraph. Executives at Liverpool and Manchester United set forth their plan to save football, working in conjunction with English Football League (EFL: tiers 2-4) President Rick Perry. They’ve called it “Project Big Picture.”

The plan includes numerous proposals, but a few stand out.

The Premier League would give the EFL $320 million, about the amount the seventy-two clubs (broken between three leagues) would expect to make from a normal year’s worth of stadium revenues. An additional $130 million would be split between the top two English women’s divisions, the men’s leagues below the top four tiers, and general administrative costs. With a few big checks, “the soul” of English football—its lower levels—could be saved, or at least supported through the pandemic.

Except with billion-dollar companies, there always seems to be a catch, doesn’t there? Liverpool and Man United have attached a set of reforms to their plan.

The Premier League would shrink from 20 to 18 teams. The Carabao Cup (a relatively un-prestigious knockout tournament that runs concurrent to the Premier League season) would be cut, as would the one-off preseason tournament, the Community Shield. The goal of these cuts, it is assumed, is to free-up more dates for inter-European competitions like the Champions League and the Europa League, the incredibly lucrative tournaments which only the best English teams qualify for. PL clubs that don’t qualify, meanwhile, would lose several games worth of stadium and TV revenue.

Currently, major rule changes and agreements require the votes of 14 out of 20 PL clubs. This proposal hopes to change that. The nine longest-standing PL clubs at any given time would be given superpowered votes. Motions would pass with support from six of those nine clubs.

Coincidentally, the Premier League has six clubs that are richer and thus generally better than the rest: Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United, and Tottenham.

These six would have the power to accept or veto new TV deals and reimagine revenue-sharing structures to favor themselves and their interests. The effects of this could be especially dramatic given the PL’s growing international audience and the windfall it brings. The underlying assumption of the project is that because the so-called “big six” generate the most money, they should have the most power and the ability to make even more disproportionally large revenues.

With newfound voting power, these big clubs could also block sales of smaller clubs to potential owners wealthy enough to fund a team to compete at the top. This exact type of sale enabled Chelsea and Man City to dominate the last decade. The project also hopes to set tighter financial regulations on EFL clubs. On the one hand, guard rails might help protect clubs from mismanagement. On the other, clubs couldn’t take the kind of investment risks sometimes required to improve and move up through the divisions. The competitive imbalance might become permanent. It’s hard not to see this as a major goal of these reforms. Clubs that are currently at the top want to keep it that way, competitively and financially, indefinitely.

Ultimately, how one feels about Project Big Picture is a Rorschach test for how they think about sports. Is the plan about saving the EFL or is it a Trojan horse power grab? Are big clubs to be admired or greeted with skepticism? At its core, is the game about the interests of a global audience or those who live for a local rivalry? Or, ideals aside perhaps, would people rather watch Arsenal play a few times a year in sunny Barcelona as part of an expanded Champions League, or battle it out against fellow-Londoners Millwall on a rainy Carabao Cup night?

But even fans of the big clubs that would benefit from reforms are entitled to ask executives, very basically, “Why do you own my football club?” “Is it about passion and shared values or making money?” Certain facts about the proposed bailout remain. Clubs, however low in the tier system, are cultural institutions that benefit local economies. They’re sources of identity and community. They provide meaning to people’s lives.

“The most valuable thing is the happiness we are able to provoke in those that struggle to find happiness in other ways, away from football,” Leeds United coach Marcelo Bielsa said of his team.

In painful times, cities and towns need their football clubs to survive.

Many PL clubs are said to be furious with Manchester United and Liverpool. On Wednesday, the Premier League rejected the plan, but Project Big Picture has set the terms of debate for the coming period of negotiation and counterproposals. In a system dominated by crisis-leveraging and ultra-rich clubs, time will tell whether there is only one way out.

Will Slater can be reached at wslater@wesleyan.edu.