The COVID-19 pandemic has upended much of the student experience at the University, but it has also given students a whole host of new learning opportunities. Perhaps nowhere is this more apparent than in BIOL 173: Global Change and Infectious Disease.

The course, which is taught by Professor Frederick Cohan, addresses the impacts of human behavior on infectious diseases worldwide. Topics covered include hunting, agriculture, transportation, climate change, and antibiotics.

“It’s [an] interesting mix of history, environmental studies, and biology,” current student Isabel Rosen ’23 said in an interview with The Argus.

The course covers a long and varied history of infectious diseases and is not focused on COVID-19. However, many of the themes discussed in the course are applicable to current events. Lauren Shackman ’22, who is a course assistant and took the class herself in 2018, feels that this material is more relevant than ever.

“[When I took this class] we were kind of always talking about, like, ‘The Big One,’ the big pandemic that’s going to happen,” Shackman said. “And we’re in it right now.”

According to Cohan, the course does not cover the science behind infections at a deep enough level to count as a core course for the Biology major, so it has typically attracted students looking to fulfill their general education requirements or those who are interested in pursuing careers related to environmental studies or public health.

“I think he manages to make it really accessible to people who aren’t super comfortable with biology, even though it is a biology class,” Rosen said.

But this semester, many students were drawn to the course out of a collective desire to better understand the events happening around them.

“It’s just in the air,” Cohan said. “You have to be thinking about [COVID] all the time. Students are always sending me stuff that they see on the news that deals with the course. It’s really different. The students are really engaged.”

Like many classes at the University, the mechanics of the course have also changed due to COVID-related precautions. Cohan teaches his 207 students over Zoom, and examinations are held online. The switch to an online format has come with challenges.

“It can be hard to stay focused when there are that many people and you can just turn your camera off,” Rosen said. “I find the class really engaging, but I think that might be [the case for] me more than some other people.”

However, holding the lectures over Zoom has not ruined the class, according to Fatai Olabemiwo, a graduate student and teaching assistant for the course.

“The interaction is really limited,” Olabemiwo said. “But you can still feel the energy when we are online, the same energy that you can feel when you are in a room with students.”

Classroom discussions have changed significantly this semester as well. Katie Sagarin, a graduate student and teaching assistant for the course, now has the opportunity to lead weekly discussion groups, a new feature for the class this semester.

“[The last time I taught the course] Dr. Cohan would be lecturing and he’d put up a question and he’d say, ‘Talk to your neighbor.’ And then he’d call on people after they had a couple of minutes to talk,” Sagarin explained.

This semester, however, one class session per week—in addition to the two other class meetings—is dedicated to discussions in groups of around 15 students, led by a teaching assistant or a course assistant and Cohan himself.

“The discussions are really about solving problems that come out of the rest of the course,” Cohan said. “We’re trying to get the students to think about how we can take the biology of an infectious disease and figure out ways to mitigate to prevent it—by changing policy, changing the way we educate, changing the way people think about different infections. We’ve had some pretty animated discussions.”

Conducting the discussions online has been a worthwhile change as, according to Sagarin, it forces people to engage in meaningful discussion.

“You can actually converse [in the discussion groups], whereas in a lecture of two hundred people—especially online—it’s hard to ask the questions,” student Hayley Lipson ’21 said.

Nonetheless, Lipson also acknowledged that there are some drawbacks to the new format.

“It’s very easy for people to talk over each other and then you miss everything,” Lipson said.

Not only has the format of the discussions changed, but the topics of conversation have as well. While COVID-19 doesn’t dominate every conversation, it is a common theme during the classes. And unlike other diseases covered in the course, discussions around COVID-19 feel less abstract and more immediate.

“A lot of the time we end up talking about current events,” Sagarin explained. “And I think that I find it cathartic and I think the students do too because they’re usually the ones who bring it up. Like, ‘Let’s talk about this experience that’s happening to us in real-time.’”

The course has always been popular, but this semester’s iteration has left an even more powerful impact on students. While Cohan stresses in the course that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely not the last of its kind, he hopes that students will be able to take the knowledge they learned in the course and be part of the change required to keep future pandemics from occurring.

“This is kind of an aim of teaching in the course, is to figure out what we have to do—not just to survive and get through this pandemic—but what general things we can do to prevent any of these other sorts like viruses from coming into humanity,” Cohan said.

Cohan also regularly reminds students of an idea that has been coined the “Socialism of the Microbe.”

“Everyone, whether rich or poor, has to make sacrifices for the public good to prevent and cure other people’s infectious diseases,” Cohan explained. “Because if we do not care for other peoples infections, those infections other people’s infections will become our infections. The sad way of thinking about this, is when you folks talk to your grandkids and say, ‘We made it through the pandemic,’ and they look at you like you’re crazy, and they say, ‘You mean you only had to deal with one pandemic at a time?’”

But this is not inevitable.

“Maybe a century ago we could have prevented HIV and now, perhaps, we could prevent [the] next SARS-like that virus from coming into humanity,” Cohan said.

Many of Cohan’s students have already taken these ideas on board. Lipson came into the course interested in public health and infectious diseases and says that the course has further solidified her interest in the public health field and drove home for her the importance of the topic.

“This isn’t going to be the last spillover event from a SARS virus,” Lipson remarked. “We’re likely to get more pandemics in the future.”

But while Cohan makes assessments about the causes of these epidemics and pandemics, he does not pretend to have easy answers to these problems. Students of public health, just like professionals working in the field, are also grappling with other problems adjacent to those faced by epidemiologists.

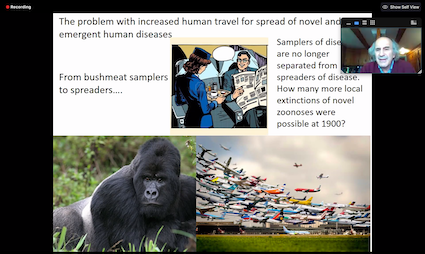

Olabemiwo, who is from Nigeria, has been able to lend some perspective to University students who may not be familiar with the realities of life in the Global South. He offered bushmeat hunting—one of the primary catalysts for disease transmission from animals to humans—as an example.

“These people that are eating [bushmeat], this is just their ordinary means of food,” Olabemiwo explained. “And not only their source of food, but their source of income as well.”

These exercises in cross-cultural understanding have clearly left an impact on at least one student.

“It’s weird to take the class in the context of the kind of neoliberalism, wanting to help people who are in developing countries, but not wanting to have that be super colonialist,” Rosen said. “That’s a conversation we’ve had a lot.”

How does the course leave participants feeling about the future? It’s hit-or-miss.

“I feel significantly more scared about the end of the world happening,” Rosen said, only partly joking.

Sagarin takes a more optimistic view.

“I try to convince myself that people will address the issues that need to be addressed in order to prevent disease,” she said. “Because we have in the past been able to do things like that. Things are already so much better for us than they used to be. If you just think about childhood illnesses… we are so protected from disease. [There are] people who stopped believing in vaccines because we live in a world where you don’t even see the diseases that you’re vaccinating for. So I’m just really hoping that we can somehow [come] together and tackle these things that need to be tackled.”

Cohan echoes this sentiment and also notes the progress that humanity has made in recent decades.

“It’s so unbelievable that we could identify this new virus and have a diagnostic for it within a month,” he marveled. “I’m hopeful that we can do these things. And that’s what I want our students to understand whether they’re biologists, or whether they’re going into government policy or whether they’re humanists and writers.”

At the end of the day, Cohan believes in the power of education and that there are solutions to these problems, and he hopes to empower students to be part of those necessary changes.

“I want this to be the last pandemic.”

Hannah Docter-Loeb contributed reporting.

Kay Perkins can be reached at kperkins@wesleyan.edu

Leave a Reply