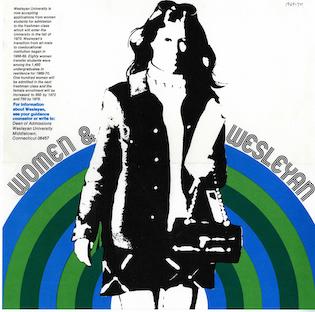

c/o Special Collections & Archives Coeducation collection

You wouldn’t know it from walking around campus today, but just half a century ago there were virtually no women at Wesleyan. Permanent coeducation at Wesleyan began in 1970, with about 100 women joining the class of ’74, but that’s not the whole story. The University was founded as a men’s college in 1831, but experimented with integrating women from 1871 to 1912, a complicated relationship with coeducation that persists today.

From 1872 until 1912, Wesleyan enrolled a small number of women in the “first wave” of coeducation. Wesleyan’s Methodist ideals, which advocated for teaching men and women together rather than separately, led to the addition of a cohort of women, who were referred to as “quails” and lived separately from the male students. The first class of women was comprised of just four individuals, who all went on to graduate with honors in 1876. Although they were part of the class, the women were announced after the men at their commencement ceremony, a testament to the fact that they still remained isolated from their peers in many aspects of campus life.

This period, dubbed the “Wesleyan Experiment,” ended in 1912 due to protest and pushback. Many male students, administrators, and alumni expressed concern that Wesleyan couldn’t compete with all-male institutions and that big donors wouldn’t be willing to contribute. A popular anti-coeducation chant was “To hell, to hell with coeducation is our yell.” The end of Wesleyan’s first attempt at coeducation actually led to the foundation of Connecticut College for Women (now Connecticut College) in 1911.

Although the first attempt at coeducation is often remembered as an attempt at integration and inclusion, in reality this was not entirely the case. In their thesis “Let Them Get Hazed,” Aviv Rau ’19 discussed how the first women on campus were able to find some semblance of acceptance because of their whiteness, but never fully belonged. Harassment from male students, an unwelcoming climate, and judgement from professors were only some of the obstacles that they faced: campus housing wasn’t offered to women until 1889.

Additionally, a small number of Black men began to attend Wesleyan in the early 19th century. In 1832, Charles B. Ray became the first Black student to attend Wesleyan. He and those who came after him faced severe discrimination, often being forced out by peers. Ray stayed at Wesleyan for less than two months. It wasn’t until 1860, around the time women started being granted admission, that Wilbur Fisk Burns—who was from Liberia—became the first Black student to graduate from Wesleyan. Then, in 1862, Thomas Barnswell became the first African American to graduate.

Tellingly, Wesleyan’s records about coeducation and desegregation are told mainly from the perspective of white men. Thus, there are definite limitations when trying to study the different facets of this part of history. Sexology, phrenology, and race sciences—theories of difference based in racist and bioessentialist ideals—were taught at Wesleyan, so even as Black men and white women were admitted to Wesleyan, their studies were strongly informed by a racist, sexist, and exclusionary curriculum. Black women were not accepted at Wesleyan until the second wave of coeducation in the 1970s.

“When we’re in a progressive institution, the attitude towards coeducation is always encouraging it and not really thinking through the material implications of bringing somebody into the space if we’re not changing the epistemologies, or if we’re not changing the conditions that they’re dealing with,” Rau said.

c/o Special Collections & Archives Coeducation collection

The second, permanent coeducation effort at Wesleyan officially began in 1970, but female transfer and exchange students began to arrive in 1968. The Graduate Summer School for Teachers (now the Graduate Liberal Studies Program) had accepted women since its founding in 1953. The administration had toyed with the idea of building a women’s college on Long Lane, but in the late 1960s had decided in favor of full coeducation. The first class consisted of 100 women, and numbers grew from there.

The first women at Wesleyan had a mixed bag of experiences. Some felt singled out and patronized; others were confronted with outright discrimination. A few women reported male professors coming on to them, or offering better grades in exchange for sex.

One female student wrote about her experience being sexually harassed by a professor in a collection of coeducation recollections for the Class of 1970’s 50th anniversary book.

“I went to [the professor] after class to ask him for feedback on what I could do to improve to an A level of quality,” she wrote. “He suggested that we meet in his office hours: the next Friday at 9 PM. When I arrived, his office was dimly lit and had a couch; he was smoking a pipe and had jazz playing. He came to sit next to me, touched my knee, complimented me, and then brazenly proposed that we have sex…and even meet every Friday evening for sex!”

Mary McWilliams ’71 transferred to Wesleyan from Smith College in 1969 as part of the Twelve College Exchange. She was disenchanted with single-sex education and found mixed classrooms to be more dynamic. Since this was pre-Title IX, which legally protected gender equality in education, there were almost no athletic provisions made for women, so she took it upon herself to swim everyday.

“There was a women’s locker room, but there were no organized women’s classes or teams,” McWilliams said.

Women got involved on campus and in the community in other ways. McWilliams was an American Studies major who enjoyed Wesleyan’s curricular variety and spoke highly of her professors. She sang in the choir at the chapel for compensation of 50 cents plus donuts, and volunteered at Middlesex Hospital.

“I had a good friend who organized the Hubbard Street breakfast program,” she said. “During that period of time there was a lot of emphasis on, like by the Black Panthers, on giving people a good start to the day…. We got breakfast out for kids in a low-income community in Middletown.”

McWilliams recalled the 1970 national student strike against the Vietnam War and Grateful Dead concert on campus, and spoke to how being part of a more diverse community opened her eyes to issues of racism and instilled in her a lifelong appreciation for diversity.

Sharon Purdie ’74 was drawn to the notion of being a member of the first class of women and was captivated by her tour of the school. In her experience as a Psychology major, the students and faculty were welcoming.

“I had a wonderful advisor who was very supportive of me and I was his first [female] honors thesis,” Purdie said.

In many respects, however, Wesleyan was not fully prepared to welcome female students to campus.

“The student clinic was operating in the dark ages with a doctor who didn’t have a clue about women’s bodies or sexual functions,” one female student wrote as part of a collection of coeducation memories.

Administrative ignorance of women’s needs also manifested in smaller ways.

“They never had enough toilet paper for women because they never understood that women use more toilet paper than men,” Purdie said.

Unlike today, where dorms are almost entirely mixed—with the exception of some single-sex floors in a few residence halls—women were housed on floors together, which fostered a sense of solidarity.

“There was a real camaraderie,” McWilliams said.

Katy Butler ’71 transferred from Sarah Lawrence, and had spent two years at an all-female boarding school before then.

“It was hard being part of such a tiny minority,” Butler wrote in an email to The Argus.

Although she noted that she thoroughly enjoyed Professor Phyllis Rose’s seminar on Virginia Woolf, in general Butler didn’t feel that professors made any special effort to reach out or welcome her. She remembered one instance where a professor had even seemed surprised that she made an intelligent point in class.

Butler was heavily involved in the 1970 national student strike, and mentioned the valuable friendships she formed.

“I was part of an otherwise all male poker group,” Butler wrote. “I made deep friends, male and female, and those relationships continued after my education at Wesleyan was over.”

50 years later, women at Wesleyan are no longer facing toilet paper shortages, nor are they the minority on campus: over half of the current undergraduate population is female-identifying. We’ve come a long way from the quails of a century and a half ago.

Sophie Griffin can be reached at sgriffin@wesleyan.edu.

Emma Kendall can be reached at erkendall@wesleyan.edu.