Content Warning: Abortion, self harm, sexual assault/abuse.

“I’d like to see Roe v. Wade overturned and consigned to the ash heap of history,” Vice President Mike Pence stated in a Fox News interview in 2016.

The rights that my Filipina-American mother had access to as a teenager in the 1980s (in the decade following 1973’s “Roe v. Wade” Supreme Court decision that made legal abortion the law of the land) seem to be in question right now. Amy Coney Barrett, the potential replacement for the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, supported a 2006 newspaper advertisement that called Roe v. Wade “barbaric.” The people currently running the free world seem to be in agreement.

Whether or not they’re legal, abortions still happen for women who are resolute in the decision not to give birth (around the world, around 8-11% of maternal deaths are caused by unsafe abortion practices). In some countries, including Honduras, women face jail time for miscarriages. In 2018, in Brazil, Ingraine Barbosa Carvalho, a mother of three, died from a botched abortion from a back-alley provider. It’s easy to predict that if “Roe v. Wade” is overturned in the United States, abortions would become a privilege for the urban wealthy, with many other women forced to perform dangerous procedures on themselves to self-induce miscarriages.

There have been few substantive representations of the abortion throughout the 21st century. Media that does incorporate narratives of women grappling with their bodily autonomy, such as the television adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale,” seem to be increasing in popularity every season. But one show cannot hold all the truths of this process: no single narrative can. So what stories should we choose to tell that shed light on this experience?

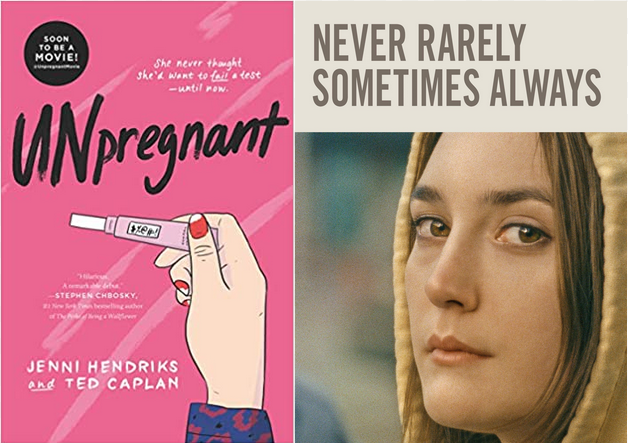

Hollywood recently seems to have settled on a surprising genre to tackle this subject matter: the buddy road trip. Two new films released this year—“Never Rarely Sometimes Always” (directed by Eliza Hittman) and “Unpregnant” (directed by Rachel Lee Goldenberg)—follow relatively the same plot. In both films, a seventeen-year-old white woman in rural America realizes that she’s pregnant and, determined to carry through with an abortion, decides to make it happen no matter the financial or emotional sacrifice. Both protagonists seek to hide their pregnancies from their judgmental parents, and thus must travel extraordinary distances to reach states that allow them to terminate pregnancies without parental consent. They recruit their best friends to go on the journey with them, scrounge up enough money and head off into the unknown.

By turning the formerly masculinist road-trip genre into narratives of women exerting their bodily autonomy, both Hittman and Goldenberg seem to offer feminist reclamations of the typical coming-of-age film. However, walking the tonal tightrope of oppressive horror and youthful exuberance turns out to be an overwhelming task, and only “Never Rarely” blends both successfully.

“Unpregnant” has enough skillful direction and attention to detail to make it engaging to watch the whole way through. The HBO Max film (released on Sept. 10) follows Veronica (Haley Lu Richardson), the valedictorian of her school who’s obsessed with maintaining a good Instagram presence and reputation with her friends. When she takes a pregnancy test in her school’s bathroom, the test accidentally falls out of her stall and at the foot of Bailey (Barbie Ferreira), Veronica’s goth-ish estranged best friend. Bailey, still having some sense of loyalty to her childhood bestie, decides not to reveal her secret. When Veronica shows up at Bailey’s door late at night with a color-coded plan on how to travel from Missouri to New Mexico’s Planned Parenthood over the course of one weekend, Bailey is willing to assist.

The opening scene of the film—the confrontation between Veronica and Bailey in the bathroom—makes it abundantly clear to the audience that this is less a story “about” abortion as it is a story about two friends who are struggling to reconnect, with an abortion being the reason that brings them together. Similar to 2019’s “Booksmart,” “Unpregnant” is a story about two women—one with her life completely planned out, the other still testing the waters of her identity—as they move beyond the differences that drive them apart. It’s clear from the get-go that Veronica needs to let go of her perfectionism and Bailey needs to face the family issues that have spawned her cynical attitude. As the film unfolds, the audience gets to watch characters address the flaws which were identifiable within the first few minutes. It’s a satisfaction that’s as easy to gulp down as the Big Gulp slushies the pair ritualistically buy on their road trip.

What sets “Unpregnant” apart is its insistence that we do not get bogged down in the drama that typically engulfs abortion narratives. Veronica’s boyfriend, Kevin (Alex MacNicoll) is a basic bro whose attempts to control Veronica’s actions are as ineffectual as they are ridiculous: there was never a question on whether she was going to get the abortion. The film bypasses any sense of internal or political conflict within the characters for a cavalcade of absurd set-pieces in their convoluted odyssey towards New Mexico: a getaway from the cops, a dazzling trip to a Texas carnival, a “Thelma and Louise” chase scene. For much of the second act, the film becomes a kind of pro-life “Get Out,” as Bailey and Veronica are duped into entering the house of a crazy evangelical couple.

Some viewers might take issue with the fact that intense social issues are stacked up against a campy plot. But I don’t think that’s a problem; plenty of great coming of age films, from “School of Rock” to “The Kings of Summer” to “Juno,” have used absurd premises to make incisive commentaries on what it means to grow up.

The real problem plaguing “Unpregnant” is the film’s inability to locate the dark humor at the center of its premise. At every step, Goldenberg bypasses the messy heart of the story: the nihilistic fact that Gen Z is screwed politically, economically, and socially, through no fault of their own. Instead, we get to witness a gooey liberalism smeared throughout the film. Characters shout “We’re pregnant and we’re gay!” not with reckless abandon but with absolute sincerity. Veronica screams at the Missouri State Legislature with righteous anger, and then seems to have recovered a minute later. Why can’t the Gen Z audience watching this just laugh at the cruel hand we’ve been dealt, and not turn it into a “it gets better” montage?

There’s so much that goes unsaid throughout the film. Each of the Black characters (played by Jeryl Prescott, Denny Love, and Giancarlo Esposito) seem to be threatening, but then turn out to be allies to Veronica. Why include these characters at all, besides making the cast more diverse?

The closest the film gets to unravelling its vexed relationship to race is when Veronica, frustrated by the trip, gestures to her body and says:

“Look, I’m not the type of person that’s supposed to get an abortion…”

Richardson’s eyes glow with confusion and fear in this scene: the stillness she exhibited in “Columbus” and the broad comedy she showed in “Support the Girls” combine into a truly exciting performance. But this confused admission of white privilege is never questioned through the lens of identity; Bailey just sees this statement as another reason why Veronica is too obsessed with her reputation. Instead of meaningfully addressing institutional problems, the film takes the easier route of solving interpersonal conflicts.

There’s one scene in the film that encapsulates all of “Unpregnant’s” wide-eyed liberal daydreaming in the face of reality. Having just come out to her friend, Bailey starts flirting with car racer and butch lesbian Kira (portrayed by the singer Betty Who). They move through a Texas mirrorhouse together, eventually falling into a ball pit radiating with gorgeous pink lighting, and make out. Where are the other people in this carnival? Can lesbians really do this in public when the film has gone out of its way to foreground the conservative world around them? And who the fuck gets to dive into ball pits in 2020?

The real loss of watching “Unpregnant” is realizing that a super dark, twisted joke could have been spun out of this abortion premise, with realistic commentary on our current status as a country. But the film is much more content to be like a carnival’s cotton candy: soft, light, recognizable, dissolving in your body without any snags. Abortion narratives do not need to be absolute horror stories, but any film regardless of conceit needs some grounding in reality. To watch “Unpregnant” is to witness yet what Zadie Smith calls “the false promise of American youth” with a fresh coat of paint on it.

There’s a world of things left unsaid by the characters of “Never Rarely Sometimes Always,” but under Hittman’s direction, it’s entirely purposeful. Like Veronica, Autumn (Sidney Flanigan) is a teenager in the process of becoming herself, one mistake at a time. The opening of the film is a jarring one: we witness a talent show happening within a high school auditorium, each student performing a rendition of a mid-20th century pop standard. Autumn’s arrival is one of extreme cognitive dissonance: even though she’s dressed up as one of “Grease’s” Pink Ladies, her soulful rendition of “He’s Got the Power of Love” sounds like Fiona Apple and draws out the disturbing blurred lines of consent in the song. Only when a male audience member calls her a slut—and the camera disorientingly turns to the audience in modern dress—do we realize that Autumn is simply performing the gender roles that have gone long past their expiration date.

After the performance, Autumn decides to fully reckon with her body, which has been giving her troubling signs for weeks. She skips school and visits a Christian health center, although she’s surprised to learn that they’re only giving her a pregnancy test she could’ve picked up at the grocery store.

Unlike “Unpregnant,” which throws in Veronica’s mom last minute to give a Catholic perspective, “Never Rarely” thoroughly engages with pro-life characters, institutions, and debates. Although Autumn is resolute in her decision to have an abortion, the fact that a Christian health clinic is her only access to reproductive healthcare makes her eager to find assistance wherever she can. Her disavowal of pro-life argument isn’t ham-fisted or dismissive either:

“They couldn’t really help me,” Autumn simply says to her cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder) and moves on with her life.

The rest of the film concerns Autumn’s trip from her rural Pennsylvania town to two New York City Planned Parenthoods over the course of the weekend. After Skylar discovers her cousin throwing up in the toilet, she steals money from her work’s cash register to fund their trip. Autumn and Skylar actually feel like small-town kids lost in the big city; they can’t afford any hotels and elect to ride the subway through the nights. At the beginning of the trip they don’t even know how MTA cards work.

Most of the film is wordless, as Autumn and Skylar meagerly but fiercely make their way through an unforgiving city and bureaucratic structures that were not meant to be navigated so independently from parents. When they run into problems, they don’t burst out into righteous anger or heated cross-talk, but rather take it in stride, managing their panic in order to survive, occasionally letting out passive-aggressive barbs. Hittman doesn’t have to force monologues or fury onto her characters; words alone can’t help their bodies. The sheer fact that Autumn has to make this journey at all is an indictment of the systems that have failed her. Every minor struggle along with the way is proof of an injustice she’s long been conditioned to accept as normal.

And yet I find myself wondering if this type of restrained independent filmmaking—long realistic takes, intimate close-ups, wordless movement—is right for this story. Does it simply keep us on the outside of Autumn’s interior life, no different from a stranger watching her on the street? Do we not have access to the racing thoughts, anxiety and surrealness of watching your future dwindle and shift before your very eyes? Does this commitment to realism drain the film from the power of metaphor for expression, especially when non-mimetically representing traumatic events?

Audiences may tend to see Hittman’s stylistic choices as indicators of “seriousness,” but I think there’s a level of playfulness in “Never Rarely” that critics have overlooked. Yes, Autumn and Skylar are put under an intense set of surveillance both by the government and by the men who are tracking their movement across the city. But the pair’s ability to expect these outside forces and lightly toy with them can be actually hilarious. This is especially true of Skylar, who’s adept at manipulating the privileged and encroaching Jasper (Theodore Pellerin). When Jasper tries to initiate a flirty conversation with the uninterested duo, the results are pretty compelling.

“I freaking love New York City, it’s kind of my favorite city,” Jasper says with a cavalier attitude. “Something about the way it’s set up, it’s like you’re forced to interact with people.”

“Sort of like this bus,” Skylar replies snarkily, making Jasper smile.

She’s playing a prank on him without him even knowing it, slowly toying with the gaze that’s been thrusted upon her.

Eventually Skylar is forced to essentially scam Jasper for money, in return for brief sexual favors. Their relationship plays like a low-key version of “Hustlers,” but stripped of all of its glamour, laying bare the purely transactional quality of male flirtation. But there’s something about the way Skylar finds moments of humor (if only for herself) that’s stuck with me. In the midst of being constantly seen, she found a way in which she could elude complete transparency, telling the truth as a sly joke.

I can’t talk about Hittman’s film without referencing the movie’s climax, one extended take that could be its own short film in and of itself. In the scene, Autumn is finally doing her intake at Margaret Sanger, a Brooklyn Planned Parenthood. Kelly Chapman, a real-life pregnancy termination counselor, asks Autumn a series of questions about her relationships as they pertain to her sexual health, to which she must respond with one of four questions: never, rarely, sometimes, or always. As the questions probe deeper into her sexual history, Autumn’s smooth veneer of jaded resilience finally ruptures. For an hour we’ve witnessed this young woman endure so much without breaking, but now—perhaps in the safest space she’s ever been—she has finally been given the privilege of vulnerability.

It’s a far cry from the abortion intake scene of “Unpregnant,” which forgoes any sense of real time and instead functions as a quasi-advertisement montage for abortion, full of glossy hospital shots, soothing voices, and strummed guitars. “Unpregnant” too often feels like the escapist rom-com Autumn and Skylar would watch at a sleepover before going back to their normal lives. When Autumn gets briefly separated from her cousin, she wanders off into Times Square, feeling overwhelmed by the barrage of screens and commercials that advertise American youth to her. Hittman’s message seems to be clear: young women like Autumn have rarely been seen on the big screen until now.

Watching Hittman’s film, I was reminded of another young woman’s NYC journey through physical and mental danger: Esther Greenwood, of Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar.” Towards the end of the novel, Greenwood has been discharged from a hospital and briefly arrives at a state of peace about her future.

“My stocking seams were straight, my black shoes cracked, but polished, and my red wool suit flamboyant as my plans,” she states. “Something old, something new… But I wasn’t getting married. There ought, I thought, to be a ritual for being born twice—patched, retreaded and approved for the road…”

As women move forward into this ungodly new era of the pandemic, they deserve the new rituals Greenwood espouses: not marriage, nor childbirth, but moving forward on the road. Although “Never Rarely” eclipses “Unpregnant” in terms of emotional sensitivity, both films mark a distinctive shift in Hollywood’s depiction of both femininity and the process of getting an abortion. The treacherous journeys America has forced women to make might be a survival story that affirms Autumn and Veronica as distinctly in charge of their own lives.

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @nathanpugh_3

Leave a Reply