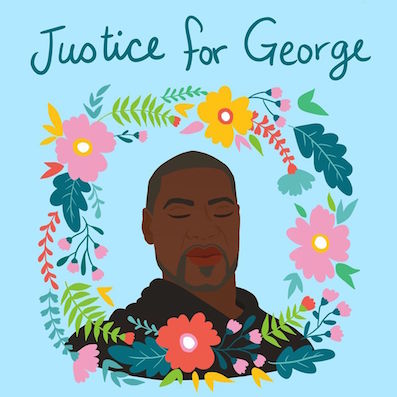

You’ve probably seen it while scrolling down your social media feed for the umpteenth time, rolling around in your bed during quarantine. It’s a simple, yet unmistakably distinct graphic of an African American man with his eyes closed as a serene assortment of flowers encircles his portrait. Above the graphic reads the striking words, “Justice for George.”

Whether it’s the Black Lives Matter protests that have been taking place across America, the protests against dictatorial President Lukashenko in Belarus, or the anti-government protests in Thailand, the world has been experiencing massive socio-political upheaval in the midst of a historic pandemic. Online, alongside shocking photos and videos of the events that have inspired these protests, one aesthetic device has widely spread the urgent messages of activists: social media graphics.

Although it’s not often given a second thought, as we tap the share button to disseminate the information, a clever graphic can reach hundreds, if not thousands of people in a single day. Given the accessibility of social media sharing, when done right, the artistic intentions of the graphic can be used to drive home a compelling point to a large audience about an issue that needs to be societally addressed.

Take the Belarus protests for example: Created by @rumadelima on Instagram, a vividly violent graphic depicts a bloodied birthday cake in the form of a riot truck sliced in half. Below the graphic reads: “It won’t come true,” referring to the failed attempts of the Belarusian police to break the spirit of the protestors. The haunting juxtaposition portrayed through the graphic is jarring, yet poignant. It exudes support for the Belarusian protester’s violent struggle against the dictatorial regime against the innocent backdrop of an unassuming birthday cake. The artist’s choices send a message of urgency to the audience, supporting the unwavering spirit of the protesters.

Graphics related to social justice movements in the United States have matched this urgency, while also spreading specific information and targeted calls to action. With eloquent fonts employed across eye-catching backgrounds, these posts increase awareness of injustice, provide up-to-date lists of organizations in need of donation, teach histories of social issues, and more. Many of these posts also use Instagram’s slideshow feature to spread various types of messages and plunge deeper into an issue than could be done with one image. To viewers who are increasingly conscious of aesthetic choices, it is impressive how captivating these text-based posts can be alongside their often more visceral photo and illustration-based counterparts.

“People struggle where they are and with the means available to them,” Visiting Assistant Professor of Art History Catherine Damman wrote in an email to The Argus. “The distribution of information—both textual and visual—has long been a key component in movements for justice.”

Historically, Damman emphasized, a major aspect of the visual message of such movements has been the controversial medium of photography.

“To me, the striking prints of Emory Douglas, the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party are indelible,” Damman wrote. “So too is Jae Jarrell’s ‘Revolutionary Suit of 1969,’ a stylish, professional tweed suit affixed with a faux-bandolier (a belt for holding bullets or ammunition). In 1971 Jarrell published an article in Jet magazine, ‘Black Revolt Sparks White Fashion Craze’—we know that the issues of Black-led movements’ ‘trendiness’ and cultural appropriation are far from new.”

More traditional art forms have been similarly elevated by this wave of social media activism. Through liking, reposting, and creating new versions of activist graphics, users have given rise to a diverse array of emerging designers such as the @shirien.creates (creator of the “Justice for George” image) while legitimizing the art form as a whole. Despite their placement within a long and complex history, the nature of these posts’ creation and distribution has allowed for significant nuance in their impact.

“I know less about ‘activist graphics’ on social media, but no doubt they bring up related, and new articulations of very old questions,” Damman wrote. “Many people have criticized the ‘meme-ification’ of Breonna Taylor. One recent, non-social media example that comes to mind is this: an uproar was raised when the artist Shaun Leonardo published an open letter accusing the Cleveland Museum of Contemporary Art of censorship when they canceled an exhibition of his drawings depicting victims of police brutality and state-sanctioned murder. More recently the voices of activists Amanda King and Samaria Rice (Tamir Rice’s mother) have been heard—Rice has served Leonardo with a cease-and-desist, asking him to stop exhibiting work depicting her son’s murder. Whether curating exhibitions or posting on social media, I would advise everyone to follow the call of King and Rice—and Black feminist thinking more generally—for an ‘ethic of care.’’

Meme-ification (the transformation of a cultural concept into easily a shareable, sometimes ironic joke) and unwanted appropriation are not the only issues that involve the visual culture of social justice. While most activism posts contain crucial, relevant information, there is the occasional false idea or belief that spreads easily through their format. One popular example of this were the posts related to the idea that Camden, New Jersey is a city in which the police were successfully defunded, leading to a reduction in crime. In reality, the Camden Police Department’s actions were closer to disbandment and reconstruction and involved several peripheral factors ignored by the post’s original creators.

This mistake was quickly corrected by posts such as the one by @jenny.jlee which read “Stop using Camden, N.J. as an example for defunding the police. Because it’s not.” Using a bold-font-over-color-background style similar to the original posts, Jenny Lee presented a well-researched account of what had actually occurred, encouraging readers to continue informing themselves on their own. By doing so, Lee identified an important lesson for those who read and repost these messages: that attractive social media posts should be a launching pad for learning and taking action on issues, and not the final stop.

Studio Art and Government major Ina Kim ’22 shared her thoughts on the issue of graphics as a whole from an artist’s point of view.

“You can tell when an artwork is done purely for illustrative purposes without much self-interrogation,” she explained. “I’m not passing judgment as to whether these are bad or shouldn’t have been posted, but I guess I’m wondering whether these became so widespread and popular because it’s easy to share, without the actual meaningful work of self-reflection, learning, or donating. I found the overuse a little callous at times. Maybe the format of these social media sites are to blame. How much could you really fit into an Instagram caption?”

Aesthetic activist posts have nevertheless injected new meaning into the medium of graphic design, popularizing the use of graphics for activism amongst a new generation of social media users.

“I think I find the visual cohesiveness [of a graphic] much more important than the regular person would,” Kim said. “And because that’s so important to me I end up looking at graphics that are much more experimental in their use of colors, fonts, and composition. Because of this I also tend to be much more judgmental of the design. I can’t help it, I like nice designs that look professional!”

Emily McEvoy ’22 is one student who has been designing graphics throughout the summer. One of her works is a graphic detailing ways to donate to Middletown residents in need. Describing the art process that she took to create the graphic, she explained how she chose to be bold and direct in her first slide to grab the attention of University students. However, unlike most graphics, which mainly aim to convey information from a predominantly visual standpoint, Emily stands by the use of words.

“You might see from some of the wordier slides in my slideshow, I’m not very into the concise-ness that these templates allow for,” McEvoy said. “I believe strongly in the power of words and prose, and I think anything other than that—deliberately writing in short, digestible slides—is feeding into the consumerist need for speed in all we do, including learning about really important topics.”

However, as McEvoy’s experience reflects, artistic choices can emphasize some messages while unintentionally failing to highlight others.

“Something that disappointed me was when my friend told me that the slide where I said to ‘Venmo’ me for supplies for Middletown residents created more urgency than the slide that literally said ‘Most Urgent Need!’ on it, when referring to donations for our direct cash assistance fund,” McEvoy said. “Reason being that the ‘Venmo’ slide has less text and the use of a different font size created more of a call to action. This really proved a lot of what I had been thinking about how graphic slideshows like this are so reductive and allow people to do under-informed, [un]deliberate activism.”

However despite their shortcomings, when done right, McEvoy believes that graphics can be a useful tool when it comes to inspiring activism and social justice.

“I think that graphics like this, and the social media culture around them, can be powerful educational tools for all the same reasons that they are harmful; they’re eye-catching and consumable,” McEvoy said. “And on the flip side, they turn people like me into designers! We get to learn about this form of art and see the psychology behind what gets people passionate about the same things we are. I hope more people interested in revolutionary liberation keep making them, not just the people telling us to ‘vote’ and nothing else. I really hope people can realize that they’re not at all a substitute for meaningful self-education, and they put a capitalist bandaid and pretty bow over life-threatening realities. In the meantime, I think this form of media is used as best it can be by more creators with intentions so much larger than pretty aesthetics.”

Aiden Malanaphy can be reached at amalanaphy@wesleyan.edu.

Will Lee can be reached at swlee@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply