Wesleyan Contracts Broad Institute, Allows for Safe Return of Students to Campus

Last spring, after COVID-19 forced students and professors to transition to online learning, Wesleyan Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Nicole Stanton started assembling a curricular planning task force to explore different options for the next semester, hoping to invite students back to campus in the fall. But amid the uncertainty posed by COVID-19, whether or not this was realistic depended on several factors: notably, would the university be able to implement mass testing?

“We began to really look into how to operationalize [the return of students onto campus],” Dean of Students Rick Culliton told The Argus. “It became clear that one of the things that we would need to make sure we had was the ability to test.”

Wesleyan consulted with epidemiologists, including Professor of Public Health at Yale School of Medicine David Paltiel, and determined that it would be necessary to test every student twice a week throughout the entire semester.

In addition to conducting biweekly testing for the student body, Medical Director of the Davidson Health Center Dr. Tom McLarney, M.D., shared over email that Wesleyan’s Pandemic Planning Committee had five criteria for the tests: they had to have acceptable sensitivity and specificity, have an acceptable turnaround time, be competitively priced, have a resulting system that would not overwhelm the University, and be FDA approved.

Culliton recalled that as of early June, whether Wesleyan could secure tests that fit these criteria was still uncertain.

“We spoke with a number of outside testing companies, for-profit companies like Quest and Abbott labs to see what it would take and frankly, between the cost and just the operation, it seemed like it would not be feasible for us to do,” Culliton said.

Despite the struggle to secure testing, on June 15 President Michael Roth ’78 sent out an email to the Wesleyan community announcing that the University planned for students to return to campus for the fall semester. This announcement followed a source of newfound hope: the Broad Institute.

“It was probably in mid-June that we became aware of the Broad Institute,” Culliton said. “They had a partnership with many of the colleges in Massachusetts. It’s a nonprofit that was created between MIT and Harvard and the researchers there have essentially repurposed some of their laboratory for [COVID-19 testing].”

According to the Broad Institute’s website, they are providing COVID-19 screening support for more than 100 public and private colleges and universities throughout New England and New York.

To Culliton and the Wesleyan administration, the Broad Institute was a feasible option for campus-wide COVID-19 testing. It was realistic in terms of cost (around $25 per test) and they promised a turnaround time of 24 to 36 hours. According to McLarney, this was superior to the 4 to 10 days offered by many commercial labs. McLarney says, so far, the Broad Institute has kept their promise to have tests back to students within that window.

The Broad Institute has also proven its capacity to handle the surging demand for testing. Culliton explained that based on the 400,000 tests administered in the United States last week, the Broad Institute was conducting 1 out of every 20 tests in the country. In one day alone, they completed between 60,000 and 65,000 tests.

However, not all schools that have partnered with the Broad Institute are testing as rigorously as Wesleyan.

“Some [schools] are just testing upon arrival and then maybe once a week, or upon arrival and then surveillance testing of about 10% of the student population,” explained Culliton. “So like random 10% would need to come in today, and then another random 10% would come next week. There’s all different models out there.”

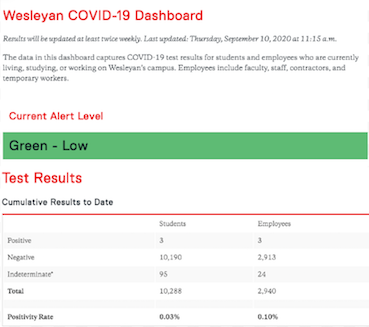

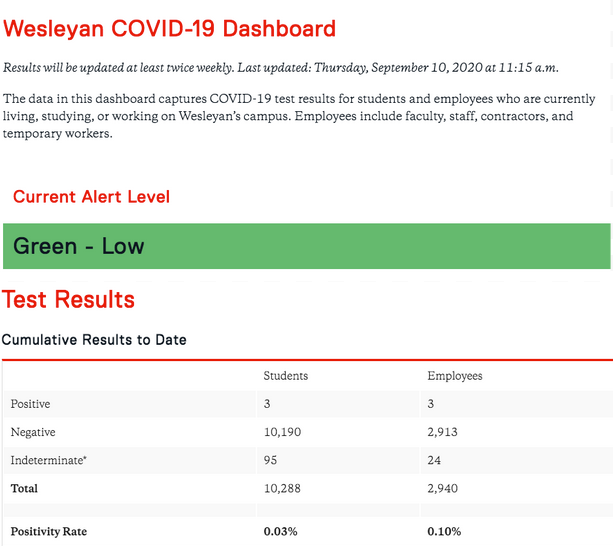

Culliton is confident that Wesleyan chose the right testing model, pointing out that some schools that test on a less routine basis have seen huge increases in cases. In comparison, as of Sept. 9, Wesleyan’s COVID-19 dashboard indicates that Wesleyan has had six positive test results campus-wide out of 13,288 tests conducted. Currently, only two of those are active cases, both employees. Since the week of Sept. 6, there have been zero positive tests reported. This is a decline from the five positive test results initially found from two staff members and three students in the week of Aug. 30.

The dashboard also tracks the current alert level, an indicator of a number of variables that impact the risk of COVID-19. Wesleyan’s alert level is currently green, the lowest alert level.

This data suggests that Wesleyan’s testing model and other preventative efforts are paying off. Still, the cost of these measures is substantial. Along with footing the bill for the COVID-19 tests, Wesleyan has contracted an outside medical staffing agency to employ certified nursing assistants, registered nurses, and licensed practical nurses to administer the tests.

“As of today, testing is estimated to cost around $3.5 million per semester,” Senior Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer and Treasurer Andy Tanaka wrote in an email to The Argus. “This figure includes the tests, staffing, location, and courier costs. These costs are currently being absorbed by the operating budget and some additional philanthropic support.”

Culliton also emphasized the incredible support that Wesleyan’s staff has provided in preparation for testing.

“We have probably, I would say, half a dozen to a dozen staff, people from different parts of the university who really came together and figured out the layout,” Culliton explained. “[They determined] how best to set things up, you know, put a plexiglass divider up between the staff and the students, you know, our I.T. people delivered the computers and set them up…I am so grateful to all of the people who really have put their heads together and tried to do this in a way that is going to be safe and effective.”

While Wesleyan has figured out how to implement mass testing for the time being, they hope to take advantage of future technological advancements as well.

“I think we’re going to continue to need to test, right through the end of this semester,” Culliton said. “You know, depending on what happens, these are all open questions, right? So if there were a vaccine, if there were the saliva test, all of those things potentially could impact what happens. Between now and the spring semester, we’re going to continue to monitor [these developments].”

Hannah Docter-Loeb can be reached at hdocterloeb@wesleyan.edu.

Eliza Kuller can be reached at ekuller@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply