While the COVID-19 pandemic brought the work of many establishments and organizations to a halt, the Community Organizing Director of Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), a grassroots migrants rights organization based in New Haven, Conn., has more on its plate than ever. ULA members are mobilizing in Connecticut cities, including Middletown, to ensure that undocumented immigrants have access to the resources they need in this time of crisis.

As the pandemic continues to ravage the United States, it disproportionately impacts the health and safety of undocumented immigrants. While many are deemed “essential workers” and carry a higher risk of exposure to the virus than the majority of the population, they have limited access to health care. Those who lost their jobs with the economic shut-down receive no unemployment benefits either; in the state of Connecticut, over 100,000 undocumented immigrants get no form of federal support. Many have to choose between proper sanitation equipment and food.

ULA has been quick to respond to the difficulties that undocumented workers face due to the pandemic throughout Connecticut. Within days, the organization set up an online fundraiser that steadily raised $40,000 in community funds to provide food, cash assistance, and supplies for families in need. ULA’s volunteers drop food off at people’s houses and disinfect homes to ensure that the virus doesn’t spread once people recover. Carmen Lanche, ULA’s community organizer who founded an ULA branch in Norwalk, Conn., also provides personal support for families dealing with COVID-19 deaths and childcare for working parents.

“Every time I leave my house, my kids spray me with mosquito repellent because they think that would be a good way to protect me from the virus,” Lanche jokingly said. “They are afraid, but I think what I am doing is important.”

ULA is not the only group in the area that recognizes that undocumented immigrants have been hit particularly hard by the virus. New Haven’s Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS), a non-profit organization that works to support immigrants, operates a food pantry every week. Since COVID-19, the pantry’s clientele base has more than doubled. Most of the new clients are undocumented immigrants.

ULA members point out that the state also fails to adequately provide undocumented immigrants with information about their rights, available programs, and health measures in languages other than English. In many cases, undocumented immigrants wrongly believe that seeking medical help makes them more vulnerable to deportation.

“I know 15 people who lost their lives from the coronavirus because they were afraid to find help—they did not get tests and died because it was too late,” Lanche said. “People are not getting help because they are scared of the police or immigration officers.”

In order to ensure that they are able to reach the people they aim to help, ULA makes sure to circulate information in Spanish. Members hang posters and post on social-media platforms. They relay news through word of mouth. When radio stations everywhere in Connecticut began to shut down, ULA Community Organizing Director John Jairo Lugo convinced ULAs local station, La Voz Hispana, to stay open.

“If something is very essential these days, it is communicated with the people,” Lugo said. “Radio is a good tool to keep sending the message to people about what’s going on around them and how they can organize themselves or what help is available in the community.”

Unfortunately, Lugo cannot go back to the station for another week because he recently tested positive for COVID-19, though he’s asymptomatic. He records his daily radio segments through Zoom and broadcasts them on Facebook Live. While he is not sure how many people still use actual radio devices, he transmits his show using an antennae in his office just in case.

ULA members share information and discuss plans of action, almost entirely in Spanish, during their weekly Zoom meetings. On May 4, the platform brimmed with twenty-eight attendees. One participant joined the meeting from behind the cash register of a Citgo, clad in a face mask and gloves. In some frames, dinner was cooking. Spouses and children shifted in the background of others. Olivia Backal-Balik ’20, an ULA member, translated the duration of the two-and-a-half hour meeting into English in the chat box for the handful of non-Spanish speakers.

Backal-Balik learned about ULA from a professor and in October, she began attending the organization’s protests in New Haven. ULA was an instant fit for her organizing ambitions: She identified strongly with Lugos’ radical, inclusive activism. Over the course of this year, she organized a coalition of students interested in expanding ULA’s model of community engagement to Middletown. The group officially began to operate around February as a kind of ULA-supporting coalition in Middletown that also worked with local groups like the Middletown Immigration Rights Alliance (MIRA) and some Wesleyan groups.

“MIRA does great work but has very different vibes from ULA,” Backal-Balik said. “Something that [we] were trying to do is to bridge that gap and to see what it would look like to do that.”

Hesitant to become a full-fledged campus group, the group still does not go by any official name. Its 17 members went four months without a group chat and only started using Facebook recently. They worry that a Wesleyan title will compromise their grassroots mission.

“We don’t want to become self-edifying through doing things on campus,” Backal-Balik said. “The whole point is to support action that’s happening in the community.”

One of the ways that this group harnesses ULA’s activism style to support the Middletown community is through working with the University’s custodial staff. Though the administration has sent most students home, Wesleyan’s custodial staff is still working. ULA’s Wesleyan support group makes calls to working custodians, many of whom are Spanish-speaking immigrants, in an effort to relate information about health, safety, and workers’ rights in Spanish. They hope to meet the immediate needs of custodians and to provide for them in the long term.

“We’re trying to build a relationship between ULA and the custodial staff so that they can know what their rights and needs are in the context of COVID and in general,” Backal-Balik said. “That way, they can go to a real activist organization, rather than a student who won’t be here in four years when they need help.”

To put pressure on Wesleyan and Middletown to adopt more migrant-friendly measures, Wesleyan students supporting ULA released a set of demands and a petition last week. The students joined community members in sending a letter to Mayor Ben Florsheim ’14 that asked to pass an executive order for more Middletown sanctuary city ordinances, such as dropping the requirement to provide a social security number for food pantry access. The petition, issued to President Michael Roth ’78, demanded that he meet with the group to discuss potential avenues for Wesleyan’s more active assistance to Middletown’s undocumented immigrants, such as privately donating some of the university’s endowment to a fund for undocumented immigrants in Connecticut.

As many of the group’s student members are low income, maintaining the same level of activism outside of campus can be difficult and draining.

“It’s harder now for some people to participate,” Margarita Fuentes ’21, who will take over as the group’s organizer next year, said. “Many of us come from positions that are not that privileged and loud homes. Some of us have bad mental health. Activism now is about meeting people where they’re at.”

In addition, virtual activism is not the most conducive platform for mobilizing a community built on informal, person-to-person interactions. Not to mention that any organization dependent on Wi-Fi is, by nature, exclusive.

“Before COVID, we had meetings with like 60 or 70 people every Monday,” Lugo said. “Zoom has been a good tool, but it’s still a challenge to a lot of people who don’t have access to Wi-Fi or who don’t have proper funds to access the call.”

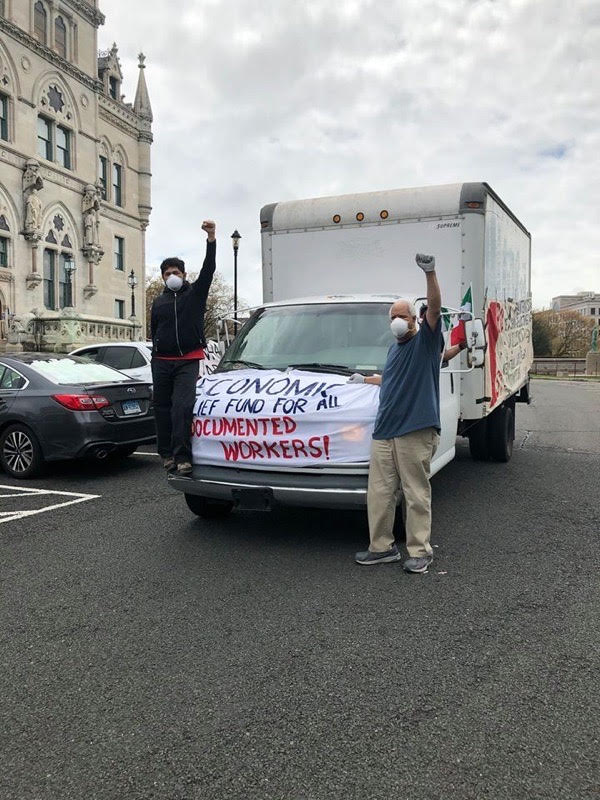

Despite these setbacks, ULA is adapting to meet new conditions and demands. On May Day, a celebration for international workers, ULA kept with its 14-year-long tradition of organizing and rallied outside Governor Lamont’s office in Hartford, Conn. This time, nobody left their cars. Nearly 20 other Connecticut organizations showed up to back ULA to demand for the state of Connecticut to follow California’s lead and set up an emergency fund for undocumented immigrants.

“It’s a challenge, but when you have a challenge, you have to adapt to the circumstances and you have to get creative,” Lugo said. “Maybe people don’t want to leave their houses, but from the window they can make noise. If you have a chain of people, like every block, making a lot of noise, I think the police and the government will hear the noise. We will make sure that they understand why the people are making that noise.”

The May Day rally embodied just a small set of ULA’s demands. Its members are already looking towards the post-COVID future. On May 14, they plan to call on the Governor to pass an executive order to erase the debt of rent, utilities and mortgages for undocumented immigrants for the duration of the economy’s shutdown. While Connecticut’s government suspended rent payments for Connecticut resident until July 1, unemployed, undocumented immigrants are still expected to obtain the necessary funds by that time. ULA’s next action, and the series of actions after it, will focus on ensuring the safety of undocumented immigrants once the virus is no longer a threat.

“This health crisis is going to pass eventually,” Lugo affirmed, “The next crisis is going to be the economic crisis, and while we are living that crisis right now, it will get worse. We will have new concerns of providing food, getting jobs, and fearing deportation. I think that the question we need to start addressing these days is how we are going to be working together in the near future because the near future is going to be especially ugly and painful for the poor people and the minorities in this country.”

As ULA and other organizations that offer assistance to undocumented immigrants in Connecticut, like IRIS, both rely on community support, it’s reasonable to assume that their funds will soon stretch thin.

“Opening up the economy would be a good thing because it will get people in increasing numbers back to work and that’s what we need,” Director of Community Engagement at IRIS Ann O’Brien said. “We can’t continue to do emergency fundraising to cover people’s bills, it’s not sustainable.”

However, the question of when the economy should open back up looms.

“We have to stand against reopening because the people who will be impacted most is us,” ULA member Catherine John said.

ULA members remain hopeful that the pandemic will become a kind of tipping point for the country’s marginalized communities.

“This crisis exposed all of the injustices in society, like not having universal health care, universal protection for people who are losing their jobs, injustices relating to the one and ninety-nine percent,” Lugo said. “Injustices related to who is dying in this crisis. We hope that people can understand that this is the best time to start organizing to try to start organizing a big movement to really change the system. We want a more equal system that can start providing for everybody, especially in a country with so much wealth.”

Fuentes sees this happening already.

“The pandemic is a kind of trigger moment,” Fuentes said. “People are standing up and saying I deserve these rights, and I always have deserved them.”

Steph Dukich can be reached at sdukich@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply