A Mosasaur skull exhibition, developed by student workers and faculty from the Joe Webb Peoples Museum, will be installed in Olin Library by the end of spring semester. The team that pushed for its installation, composed of Paleontology Curator of the Joe Webb Peoples Museum Professor Ellen Thomas, Andy Tan ’21, and Yu Kai Tan ’20, was also responsible for the creation of the Glyptodon and Deinotherium exhibitions in the Exley Science Center.

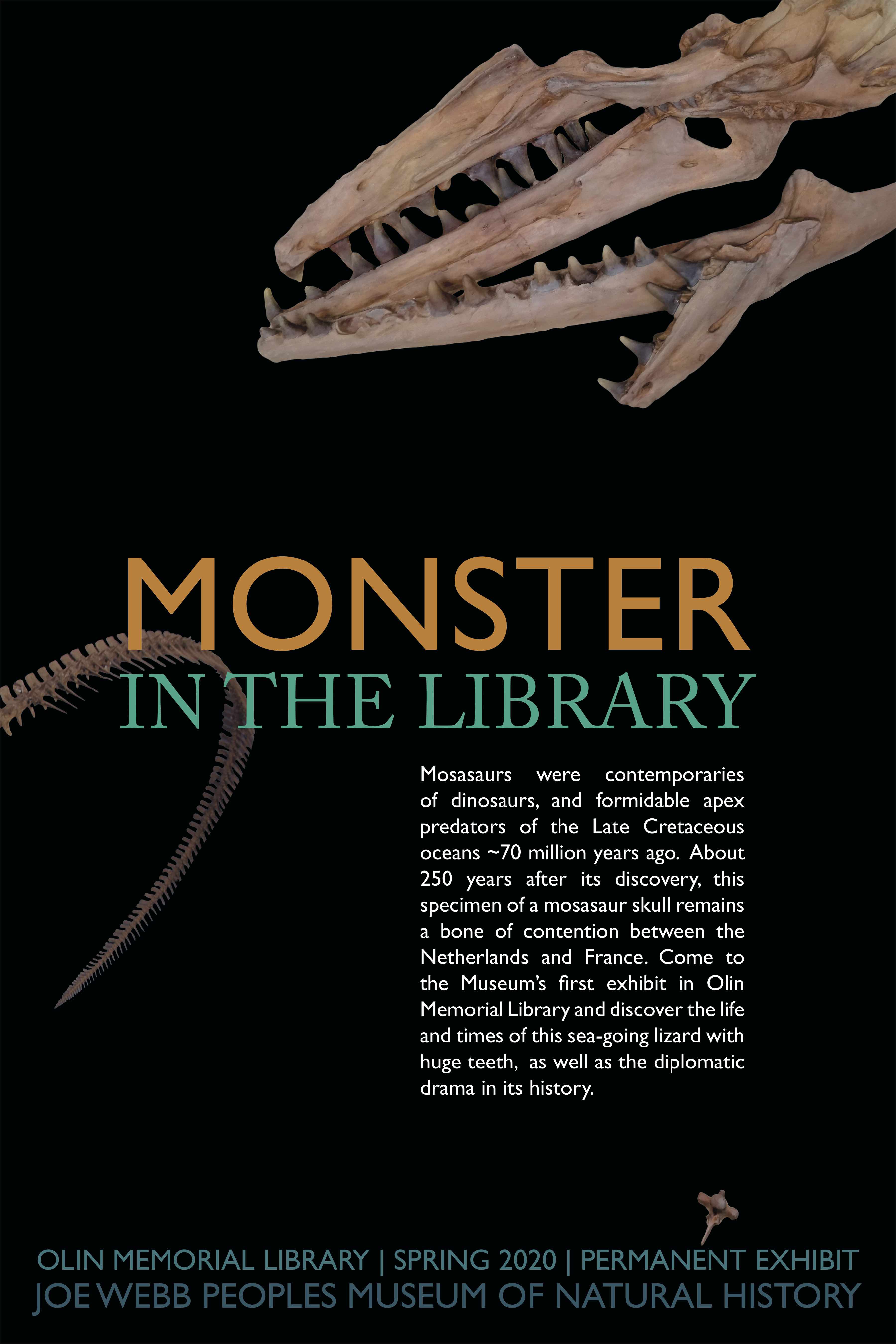

The Mosasaur was a species of lizard that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, 66 to 68 million years ago, when dinosaurs had not yet gone extinct. Jurassic World fans will recognize the Mosasaur from a scene featured in the movie.

“There’s a scene in [the movie] where they hang a shark from a rope over a swimming pool and something comes out and eats the shark,” Thomas said. “That’s a Mosasaur.”

The first Mosasaur skull was discovered by quarrymen in the Netherlands in 1829 and is now on display in Paris, France. The skull that will be displayed is a replica of the one in Paris that was gifted to the University by graduate Orange Judd in 1871. The skull, as well as around 900 other casts, was purchased with the goal of displaying the specimens in the University’s first museum. The museum was located in Judd Hall, but was shut down to make room for laboratory space.

“Around the 1930s, the sciences sort of shifted to more molecular approaches,” Y.K. Tan said. “DNA and those things started coming into view, so by 1957 when one of our professors, Joe Webb, was on sabbatical the school was like ‘We need lab space and this person is not here to make noise, so let’s close down the museum and store everything away.’”

When the museum closed, the pieces in the University’s collection were put into storage in the tunnels under Foss Hill. Since then, the Joe Webb Peoples Museum team has been working to sort through the remaining items that were not vandalized or stolen, and develop exhibitions to display them on campus. The Mosasaur exhibition is the latest result of those efforts.

“The first thing we did was take it out of storage,” Y.K. Tan said. “It was a nerve-wracking process because every time something comes out of storage, no one has seen it for over 60 years and you don’t know what condition it’s in.”

As A. Tan explained, the goal of the curators is not to make the skull look as it did when it was first replicated.

“What we try to do with the casts is not to remake it into how it was done in the 19th century, because with our experience from mold casts, we know that some of the paint jobs weren’t very accurate to how the fossils looked like, [so] we try to make the casts look more like the actual fossils,” he said.

Once the process of restoring the Mosasaur skull was underway, the team needed to decide on a location for the exhibit. They specifically wanted to reach students from majors outside of the sciences with the Mosasaur installation.

“We’ve always been talking about doing something outside [of Exley],” Y. K. Tan said. “As an anthro major, I hear a lot of people complaining ‘I never know where you guys put your exhibits’ or ‘I never go to Sci Li,’ that sort of thing.”

Olin Library seemed like an obvious choice to the team.

“The new director of the library, Andrew White, is very supportive of natural history collections and collections in general, so that’s why we started having more exhibits outside of the museum,” A. Tan said. “He encouraged us to do the tree of life exhibit in Sci Li right now and because of how welcoming he is, we proposed that we do [an exhibit] in the library.”

White agreed to host the exhibit in Olin, so that students from a variety of majors can see the Mosasaur once it is displayed.

“We have a table that’s being built by our carpenter and the Mosasaur head is going to be on the top with glass over it, so that means if you’re studying and you happen to pick that table, you’re going to see a Mosasaur,” Thomas said.

The team hopes that by placing an exhibit in a location more accessible to students from various different majors, more people will become aware of the collections in the University’s possession.

“Wesleyan has these amazing resources that are unique and no one knows about them…we want to advertise that we have them,” Thomas said.

A. Tan echoed Thomas’s sentiments.

“We’d really like to have more people know about the collection and keep in mind that it’s a resource they can use for any project they want, like drawing or any kind of research, be it English research or historical research or the history or philosophy of science,” A. Tan said.

Most of the work the students do for the museum involves restoring the specimens so they can be displayed in exhibitions.

“We have various students involved with repairing these objects,” Thomas said. “There are things that have been sitting in crates since 1957 so we have students repairing them, repainting them, writing blogs about them.”

There are many other jobs open to students besides restoration, ranging from creating art for exhibits, writing blogs about specimens and even the engineering that goes into simply ensuring that the specimens stand up properly in their displays. The interdisciplinary nature of the exhibits gives students from various academic backgrounds the chance to work with casts in the museum’s collection, which as A. Tan points out, is a rare opportunity.

“It’s not easy to get a cast of a Mosasaur skull and not everyone will have one to study with, so it’s invaluable historically and scientifically,” A. Tan said.

In the past, student involvement has ranged from drawing specimens, writing blogs about them, and studying them as thesis subjects, but Thomas stressed that she is open to any project a student may be interested in pursuing.

“If someone can think of something else to do, we have space for that,” Thomas said. “It depends very much on what someone’s interests are and what they want to do, and we’ll see if we have the money and time to do it. And if so, then we’ll do it.”

Sophie Wazlowski can be reached at swazlowski@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply