CW: Gore, stalking.

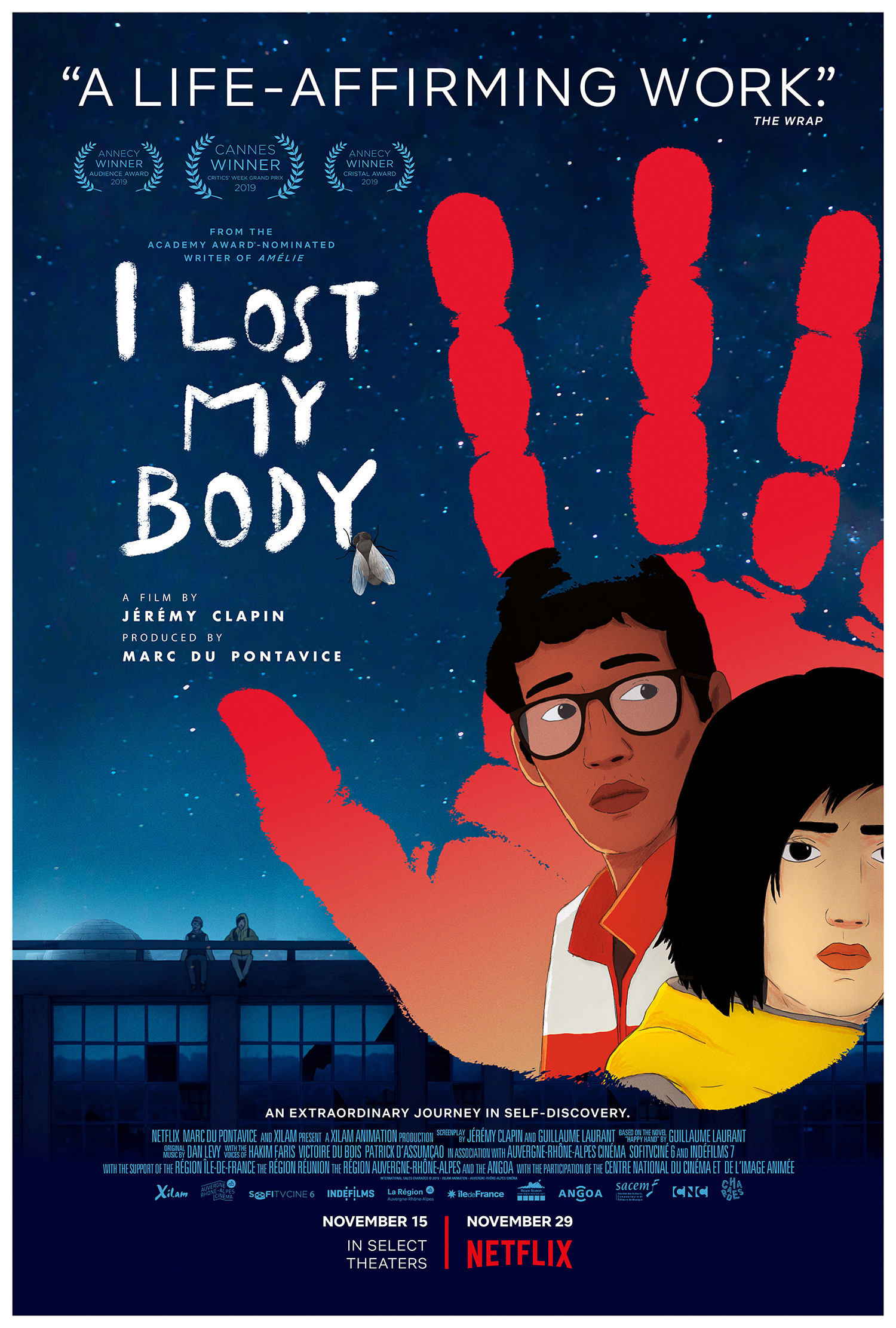

A movie that involves both a severed hand and a love story seems destined for tonal havoc. But “I Lost My Body,” a new animated film by French director Jérémy Clapin, manages to thread the needle—almost. This Oscar-nominated, Cannes-prize-winning film tells the story of Naoufel (Hakim Faris), a Moroccan-French pizza delivery boy living in Paris. After his parents die in a car accident, he lives an aimless life until he meets Gabrielle, a librarian, on one of his rounds. Well,“meet” is putting it strongly. They talk over an intercom for a few minutes because the buzzer for her room is broken, then part ways. When Nauofel gets home that night, he looks up her number, gets a job at her uncle’s carpentry workshop just to be close to her, and makes charming overtures to win her hand. If this sounds stalking to you, you’re correct.

An hour into the film, Naoufel finally confesses his feelings for her, and reveals who he is (“I’m the Pizza delivery boy!”). Gabrielle understandably freaks out and rejects him. In response, Naoufel gets drunk, shows up to work the next morning, and accidentally saws off his hand.

In the end, he manages to convince her to go out with him.

But there’s no denying that this first act of the film is extraordinarily creepy. What’s worse is that it’s all played flat, meant to be taken by the audience as almost whimsical. It’s a major blemish on one of the best and most visually innovative animated movies of the year.

Some might counter this claim by saying something like, “actually, stalking is an essential part of the film. It helps establish its creepy tone, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in an animated feature.” I disagree. It’s one thing to present this problematic behavior in a deconstructive way—in other words, to show Naoufel stalking this woman as creepy. This could easily have been accomplished by adopting a darker color pallet, more ominous music, or other basic stylistic changes. But no; Clapin instead seems to be unconscious of how troublesome his character’s behavior is.

For example, take the scene where Naoufel looks up Gabrielle’s number in the phonebook. The tone of the scene is comic: Naoufel hides in the bathroom, calling all the Gabrielles in his borough of Paris. Outside, his roommate bangs on the door and asks, “What are you doing in there? I need to go to the bathroom!” As viewers, we’re clearly supposed to respond, “Ha! Poor Naoufel, going after this woman while his roommate gets in the way!” But look closer, and the stranger the scene becomes. Along with his phonebook, Naoufel holds a legal pad with over forty names on it. So far, he’s crossed out twenty. He’s so obsessed that he’s unable to give this activity a break, just so his roommate can go to the bathroom. And he speaks in an almost detached, sleepy tone, moving zombie-like from one number to the next.

The problematic nature of the story is a shame, as the animation in this film is dazzling. Clapin uses a combination of hand-drawn and rotoscoped animation, resulting in a dreamlike, yet gritty representation of mid-90s Paris. Rotoscope is an animation process where a scene is recorded in live action, then traced over by an animator. The music video for the A-Ha song “Take on Me” is a popular, if slightly silly, example.

The artistic chops of Clapin’s team come to fruition in the movie’s second plot, which interacts with the unfortunate romance plot. What does this second plot consist of? A severed hand.

I’m not kidding. In a fantastical twist, we follow Naofel’s severed hand, as it crawls out of a hospital refrigerator and scurries along the streets of Paris like a spider, dodging rats and cars, on its way to reunite with its master. This episodic survival narrative, a far cry from the predictable romance plot, provides an interesting counterpoint to the film, and helps secure its melancholy tone.

Of the two plots, the “hand plot” is unquestionably the more visually interesting and exciting. There is always something impressive about a movie that manages to tell its story entirely visually, without the need for dialogue. It is even more ambitious to do so without facial expressions—yet Clapin pulls it off. The decision to send the hand through scenarios of physical danger is a wise one, as it allows the story to be told entirely through physical movements: hand fights rat; hand jumps off building with an umbrella as parachute; hand crosses frozen stream.

No other film in the past ten years has functioned as a purer example of the power of animation. If “I Lost My Body” will be remembered for one thing, it’s for showing something that simply cannot be done with live action, or even with 3D animation—either would render the gore of the situation too real. The film can only thrive in this middle ground of 2D animation, playing with the morbid without crossing over into the disgusting—although Naoufel’s plot toes the line.

Trent Babington can be reached at tbabington@wesleyan.edu or on twitter @trentbabington.

Leave a Reply