c/o imdb..com

Halfway through “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue) gives up. After spending an hour of screen time searching southern China for a former lover, Hongwu walks into a movie theater and puts on 3D glasses.

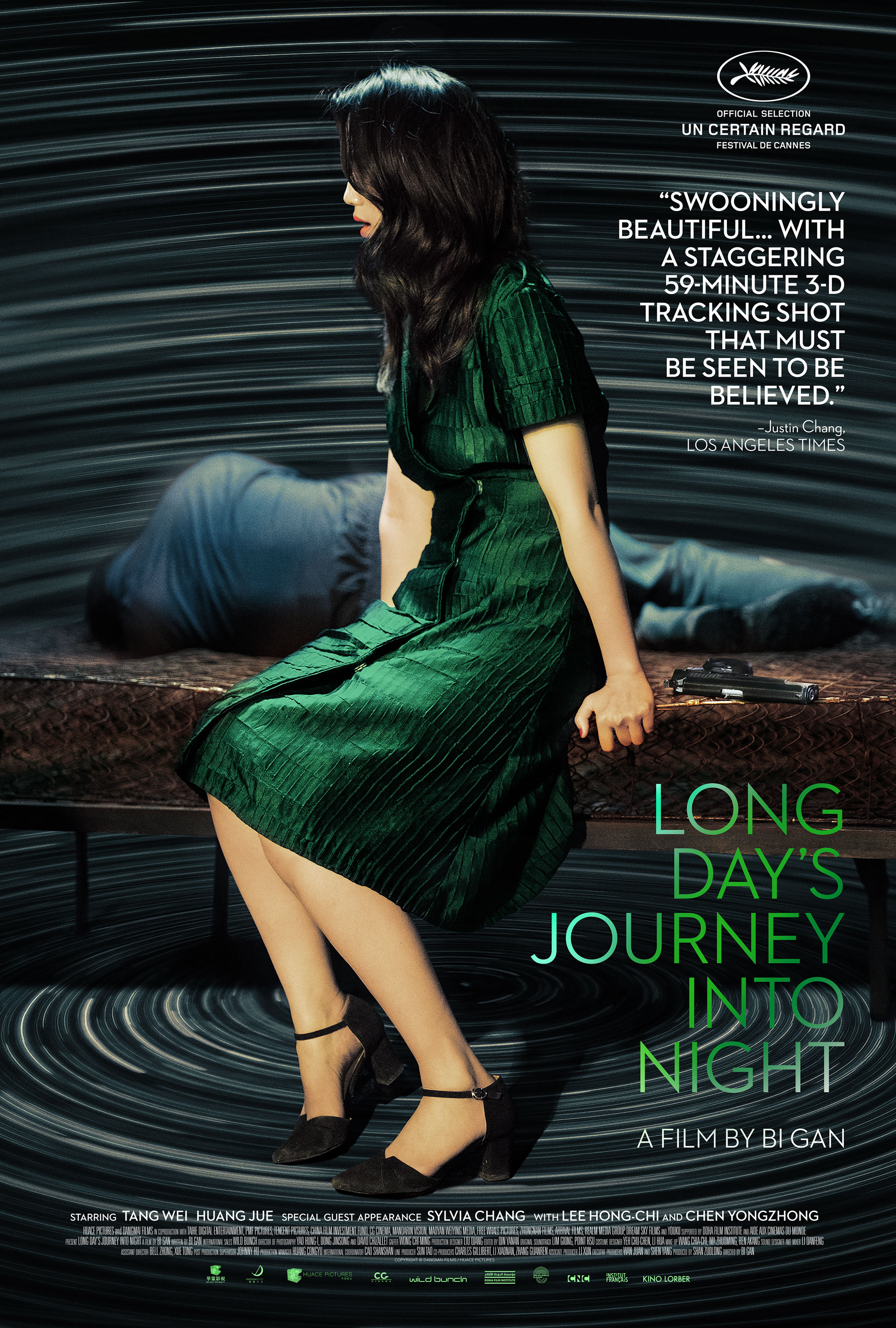

Taking the cue, the audience—that is, the couple hundred students packed into the Goldsmith Family Cinema for the film’s Wesleyan premier on Jan. 27—does the same. The question that’s been on everyone’s minds since walking into the theater an hour ago now comes to the forefront, and anticipation becomes palpable: One of the marketing ploys for “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” the second film by Chinese director Bi Gan, is that it finishes with a 59-minute uninterrupted “long take.” And, it’s in 3D. So we wonder: Are we about to witness a brave new work of art or an hour-long gimmick?

The answer, thankfully, is much closer to the former than the latter.

The shot itself is magisterial. Its most technically challenging moments include a ping-pong match, a zip-line ride, a game of pool (just the right balls must be sunk for the filming to progress), an aerial shot (the camera had to be attached to a drone, flown around, then detached and carried away by another camera man), and a dance competition with over 20 extras. Oh, and this was all shot at night in the middle of winter on location in Guizhou Province.

Is Bi Gan showing off? Yes. But not without purpose.

This second half of the film is a dream sequence, and Hongwu falls asleep in the movie theater. He “wakes up” in a mine shaft, is introduced to a strange childhood version of a dead friend (his opponent in that ping-pong game), and, leaving him behind, runs across a woman who slightly resembles the woman he is searching for (who’s played by a different actress). They talk for a few minutes, walk away from each other, and eventually run into each other again. Hongwu pursues her just as one might in a dream: lethargically and without as much urgency as he would in real life. At any rate, the questions raised in the first half of the film—“Will he find this mysterious woman?”—are abandoned.

These strange differences, slight variations, and transformations that the dream sequence facilitates are the most interesting part of the movie to watch. The first half of the film, the search, is something of a film noir crossed with Tarkovskian aesthetics; one doesn’t have to be particularly astute to notice the leaky buildings, shots of water foliage, and glasses sliding off tables, as allusions to “Stalker.” The soundtrack, too, seems to be a homage.

I don’t know what to say about these jumbled gestures in the first half of the film. Things really only begin to move in the second half, when the dream sequence transforms, and in a strange way resolves, the questions set up during the preceding hour. Whether or not this second woman is the same as the first, they nonetheless hook up, and that’s the end of the film. It’s a strange sort of fantasy-resolution, almost a parody of stories, certainly of dreams, implying that they provide a sense of closure harder to find in real life, as represented by the unresolved search of the first half of the film—a web of aimless country drives, dead phone numbers, and listless conversations with acquaintances of the person Hongwu is searching for.

Understanding the metaphor and subtle meaning behind the the second half of the film makes clear that all those technical acrobatics—shooting in one take, filling said take with thousands of chances for error, and rendering in 3D—are essential to making the dream sequence work.

Moving the camera without cutting, simply drifting from place to place, carried from situation to situation, creates an unearthly, eerie quality of camerawork that mimics a dream.

The 3D element also plays a role here, as it enhances our sense of depth and space, another quality that Bi associates with the lucid dream. How exactly depth and space make a movie more dreamlike is difficult to describe; all I can say is that it makes the experience feel off, as if you are in an altered state of mind.

Even the nighttime set makes the world seem only half-imagined, only half there. Little islands of light, from houses, roulette machines, and a dance party add to the feeling that we are moving not through a fully realized waking world but through disjointed memories, existing in a cluster but not quite cohering. We understand roughly where everything is in relation to everything else, but our knowledge of the empty space between is limited.

Perhaps all of us dream differently, but for Bi, at least, this is how dreams look. And watching it on the screen, the result is convincing.

The significance of this achievement should not be understated. Dream sequences are unusually important in a medium like movies and TV. One of the basic lessons in screenwriting is that everything must be external, including a character’s thoughts. Otherwise, we have difficulty understanding our character’s actions, as they remain stuck inside their head, which we don’t have access to. Film—and plays for that matter—do not have the luxury of prose fiction, where a character’s thoughts are easily related via interior narration. Instead, contortions must be undergone to show what’s happening inside a character’s head, making the internal external. And one of the most efficient ways to do this is to create a dream sequence: take a character’s innermost desires and put them on screen.

If Bi has found a way to enhance and make more immersive the experience of being inside a character’s mind, then “Long Day’s Journey into Night” should be counted as a step forward, both for the exploration of movie character psychology and for the use of the long take and 3D.

Trent Babington can be reached at tbabington@wesleyan.edu.